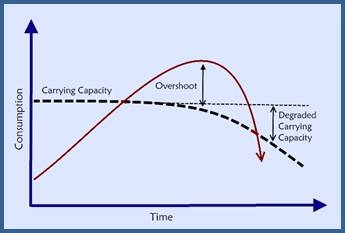

When we try to look for historical societies that were sustainable they are hard to come by. More primitive peoples usually got round the fact they degraded their immediate environment by moving to another spot to live and thus allowing the resources they used in the original place to replenish.

In more advanced static societies we have many examples of the boom and bust collapse of a population in overshoot including Rome, the Maya and the classic example, Easter Island. But we do have one example of a sustainable society that existed for hundreds of years with almost no population growth and that was medieval Europe. Unfortunately this is not the sort of sustainable that many modern users of the word have in mind.

THE ETERNAL VILLAGE

Let us begin by looking at an ordinary European village in the seventeenth century. This village, Sennely, which has been carefully studied by Professor Bouchard, has a claim to being considered typical. 1 A population of some 500 to 700 persons is typical enough. The village’s reliance on grain for bread-making as its chief crop is more than typical—it is universal. The thatch-roofed, windowless farmhouses, with their two rooms, attic, barn, and cowshed, are certainly normal.

Sennely is relatively isolated, as are most villages. Not that the city is far away; it is close enough so that tenant farmers pay their rents to absentee landlords in the city of Orleans. But the outside world does not impinge on the daily life of the villagers. Like most villages in preindustrial Europe, Sennely was a community of subsistence farmers whose needs were supplied locally: the rye grain, for bread; the cattle and pigs; the orchards that supply apples, pears, plums, and chestnuts; the garden vegetables; the fish in the ponds and the bees kept for honey and wax. Sennely had a miller, an innkeeper, a smith. There were part-time shopkeepers and weavers in residence. A villager hardly ever needed to go abroad.

This small, self-sufficient world is typical in another respect. It is fragile. The balance between resources and population is an uneasy one. The land is poor in Sennely. Water drains poorly. Evaporation from stagnant pools and ponds creates permanent ground fogs. This is not good land for growing grain. The poor soils of Sennely may not be typical. What is typical is the constraint under which the farmers operated, inasmuch as they had to grow grain, even though they would have been better off if they had concentrated on raising cattle.

What Sennely had in common with practically all European villages before the mid-nineteenth century was the need to be self-sufficient. Underdeveloped transportation and commercial networks forced the rural population to grow all essential crops, even those for which the land or the climate were unsuitable. Sennely could not buy grain and sell livestock in exchange. It was condemned to make do with its sandy soil. Unable to grow wheat, the preferred grain crop, Sennely planted rye. Poor yields were compensated for by the vast size of the village land, a good deal of it wasteland, swamps, and heath. It took about two hours to walk across the village’s territory and half the farms were spread out at a considerable distance from the village center. This dispersed habitat, an adaptation to the poor soil, no doubt goes a long way toward explaining Sennely’s lack of social cohesion. Although the village did possess a clear center, a street of houses, a square, a church, and a cemetery, most of the farms lay hidden in the distance, each of them screened by rows of oak trees.

Not surprisingly, travelers described the chief personality trait of the peasants of Sennely as suspicion. They seemed suspicious of outsiders and of each other and not much given to talking freely. Their physical appearance was remarked upon as distinctive. They tended to be stunted, bent over, and of a yellowish complexion. They were not born that way. The little children were said to be good looking, but by the time they had reached the age of ten or twelve, they assumed the generally unpleasant appearance of their elders. They did not look healthy. Their bellies were distended. They moved slowly, they had poor teeth, their growth was retarded. Girls reached the age of 18 before first menstruation.

What we have here, then, is a group of people living on the edge of deprivation. Malnutrition was normal in Sennely in the late seventeenth century. There are hints of better times in the past, but by the time the records become abundant enough for a clear analysis of this society, Sennely appears as a fragile entity, vulnerable to disease and, somehow, just barely, kept going in spite of the constant, threatening presence of death.

One third of the babies born died in their first year. Only a third of the children born in Sennely reached adulthood. Most couples had only one or two children before their marriage was broken up by the death of one parent. Women married late, at about age 23, on the average. Any given 100 women in Sennely would bear about 350 children in the course of their lives. Of these, only 145 would reach adulthood and marry in turn, 75 of them female. Allowing for 5 girls who would not marry, only 70 adult women were available to replace the 100 women of the preceding generation. Yet the population remained more or less constant. The villagers probably made up the deficit by marrying the daughters of transient artisans and laborers. When death struck a household, no time was wasted; widows and widowers remarried right away. Most first marriages occurred in the wake of a parent’s death, so that the farm and the family could continue to function with a normal complement of hardworking men and women.

Fragile in the face of its poor harvests, constantly threatened by hunger and disease, Sennely just barely managed to reproduce itself, to hold on to life behind its hedges. Yet, for all that, Sennely was not badly off when compared to other villages. The peasants of the nearby Beauce plateau, a prime wheat-growing region, looked down with contempt on sullen, watery Sennely. But when harvests failed in the Beauce, there was nothing to fall back on, since all the land was plowed for wheat. A succession of bad harvests was enough to transform the peasants of the Beauce into starving beggars. Having put all their eggs in one basket, they were helpless when the wheat fields failed them. They took to the road, begging for food. And it is on such grim occasions, when the peasants of Sennely open their houses to starving vagrants and feed them generously, that we notice the hidden strength of Sennely’s economy. Although it lives on the margin of poverty, Sennely never faces an all-out famine. Its inhabitants must have learned long ago that their meager grain crops had to be compensated for by making full use of the heath and ponds. They depended on their pigs, their cattle and sheep, their vegetables, fruit orchards, and fishing. It is this diversity, together with a low population density, that kept catastrophic famines away.

Not that everyone in Sennely enjoyed an equal level of protection against hard times. This was not a society of equals. The better-off farmers owned a team of horses and a plow. They did not exactly own their farms. They leased them from absentee landlords, but their customary rights to the land were so ancient that they were not in danger of losing them. These leaseholders belonged to the European-wide category of rich peasants known as laboureurs in France and as yeomen in England. Their wealth, however, was entirely relative. Distinguished by their possession of the expensive team and plow, they nevertheless lived just this side of poverty. It is only when they are compared to less fortunate peasants that they appear rich.

The estates of the laboureurs of Sennely can be evaluated at somewhere in the 2,000 livres range. By comparison, the social category just below, that of the renters (locataires) who do not own horses and plows, was made up of families whose worth was only in the 600 livres range. These tenant farmers were constantly in danger of losing the land they rented and of being reduced to the level of hired hands. Hired hands (journaliers) in Sennely owned nothing except, perhaps, the roof over their heads, a garden, a pig.

There was another category of villagers, that of the artisans who lived in the village center and owned no land. Their level of fortune lay somewhere in between that of the renters and hired hands. About half the peasant families in Sennely belonged to the better-off categories of leaseholders and renters, who had some property. The other half of the village’s population was made up of the families of hired hands and artisans who had no land at all.

A little to the side of these ordinary peasants, living on the main street of the village, their houses marked with painted signs indicative of their profession, we find three successful entrepreneurs: the smith, the miller, and the innkeeper. These families were among the most prosperous and influential in the village community. Barely involved in working the land, they dealt in goods and money. The innkeeper was also a contractor and a moneylender. There were horses and cows in his barn, his sheep grazed in the pastures, but he also bought up the grain owed to the Church and sold it on the open market. A handful of part-time shopkeepers of lesser wealth and stature completed the picture. They had a shop, a house, and a garden on the main street, but they could not live from trade alone. They also farmed and they dealt in cattle, hides, and wool.

On the fringes of village society, linked to it only in the sense that they owned property here, were rich outsiders who constituted the local elite. The priest, to begin with, whose house was the most imposing in the village. The priest had a comfortable income from rents and tithes assigned to the Church. He had a garden and an orchard. His house was a mansion of sorts, complete with salon, parlor, library, chapel, butler’s room, stable, bakery, barn, and servants’ quarters.

Side by side with the priest who presided over the Church’s real estate interests in Sennely, there were three or four other outsiders, substantial men of property: a notary, a business agent, and an estate manager. They represented absentee landlords, but they also had property of their own. The estate manager had two farms which he leased out, rents from a number of tenants, and a large herd of sheep. He lived in a six-room house and he had a servant.

On the outer fringes of Sennely’s territory, there were three small châteaux, belonging to wealthy gentlemen who were seen only occasionally, as they lived in the city and resided in their country châteaux only in summer or in the hunting season. The wealthiest of these gentlemen owned six farms locally, the others had three farms each.

Leaving the priest, the gentlemen, and their managers aside, we are still left with a village community marked by sharp contrasts of wealth and power. The landless peasants and artisans live in grim poverty. Their cottages are small, dark, and cold, they cannot afford firewood, they own only the clothes on their back and a pair of wooden clogs, their larders are often empty.

The more substantial farmers, meanwhile, are likely to possess reserves of bacon and cheese, wardrobes full of warm clothes, and much bedding to ward off the cold at night. In spite of these differences, there is no sign of strife in the village. This requires some explanation, especially since Sennely lacks most of the social controls one may find elsewhere. No resident lord provides leadership here, the priest’s influence is thin. At most, he visits a family once in three years. As for family ties, they are too weak to provide cohesion.

Family relations, as revealed in the parish registers where births, marriages, and deaths are recorded, confirm the casual observer’s view of the peasants of Sennely. Each family is on its own here. It is a bare-minimum family, consisting of a couple and one or two young children. For those who look back to the rural past with nostalgia, expecting to find large, noisy, heart-warming throngs of adults and children all living merrily under one roof, the evidence in Sennely is bound to prove a disappointment. These seventeenth-century peasant families are as isolated and as unstable as are modern families of wage earners living in impersonal housing projects on the periphery of industrial cities.

Grandparents are hard to find in Sennely, and so are aunts, uncles, or cousins living under one roof. The bread and bacon wrung out of each homestead cannot stretch to feed more than two adults and their babies. Bitter experience taught the peasants of Sennely to be calculating. They did not marry until death had cleared the way for the formation of a new family. Most young men and women waited until one of their parents had died before marrying and raising a new generation. As long as both parents were alive, the addition of another mouth to feed would have put a strain on the family’s resources. As soon as one of the parents falls ill, however, the grown son or daughter must contemplate marriage to a partner who will replace the dying parent on the farm. There probably is not much sentiment involved in such matches. If the priest is to be believed, his parishioners marry only out of calculation. They do not worry about the bride’s pretty face, they ask only how many sheep she will bring into the family. Sexual need probably does not influence the decision very much either, since promiscuity at an early age is a trademark of Sennely’s young. Outsiders comment on this, some expressing shock. The boys and girls of Sennely, it seems, do not need to wait for marriage. They pet and kiss and fondle each other freely. Marriage, in this perspective, is business rather than pleasure.

The new family, founded in the shadow of death, is a partnership established for the purpose of continuing the timeless battle against hunger and solitude. It is not a very solid partnership. It will be broken up by the death of one of the partners within ten years or so. Just time enough to have a baby in the first year and several others, at two year intervals—four or five children in all. One or two of these will die of a contagious disease, aided by chronic malnutrition and unsanitary surroundings. When the mother herself dies, often in her early thirties, and usually from complications following childbirth, the widower is left with two or three orphaned children in his care. Almost instantly he finds a new wife. Half the recorded marriages in Sennely are second marriages of this kind. Should both parents fall victim to one of the recurring waves of murderous food shortages accompanied by illness, the children will be taken care of by the village. Orphaned children are not so much absorbed by relatives as by legal guardians appointed by the community. Unless the orphaned children are very young, they may not experience their parents’ death as a profound dislocation, since it was the custom, anyway, especially among the landless families, to hand children over to more prosperous neighbors when they reached the age of seven or eight. They were old enough, by then, to become servants, apprentices, or shepherds. By the time they were 14, they were able to give a full day’s work to their masters, so that caring for an orphaned child was not necessarily a losing proposition.

Few could afford the luxury of sentiment in Sennely. This was a society on a perpetual war footing, mobilized against the inroads of death, closing ranks in the aftermath of catastrophe. The men and women of Sennely were too much concerned with making a bare living and burying their dead, to lavish feelings on each other. Parents were not in a position to care for their children beyond their early years, nor were children prepared to come to the aid of destitute or sickly parents. Orphans were taken care of, not so much out of pity, but because they were human capital. A reasonably healthy orphaned girl, after serving some years as a kitchen maid in her guardians’ household, could look forward to a marriage proposal from an older widower. Not Christian charity or family affection but labor shortages activated social welfare provisions.

Having observed how fragile family bonds seem to be in this village, we are naturally led to ask how the community functions when common action is called for. In what sense does one belong to Sennely? What are the sources of authority here, how are common standards of behavior agreed upon and enforced? To the extent that one can answer these questions one reaches the conviction that authority in Sennely does not have its source in kinship ties. There are no clans, no elders or patriarchs obeyed because of their position within a network of family relations. To the extent that there is a common identity in Sennely, it rests not on blood, birth, or lineage, but on artificial, man-made, deliberate solidarities.

All the families of Sennely, rich or poor, are members of the formal village community. This is a legal entity, capable of borrowing money and raising taxes. Its will is expressed by means of periodic assemblies. Major decisions are made by formal or informal polls of all the heads of household present. Although everyone has the right to speak at village meetings, in practice most assemblies are attended only by the more substantial taxpayers. The village assembly also manages and audits the financial affairs of the local church. It prevents disputes from arising, takes measures to protect the village against marauders, vagrants, and wolves, appoints shepherds for the common herd and a schoolmaster if the village can afford one.

The assembly’s functions are important, but the villagers are more deeply, more emotionally involved in other formal organizations. Although the priest may not be important to the villagers, they view the church as theirs. They feel at home in this building their ancestors built and they maintain. The church and the adjoining cemetery constitute the heart of the community. From the priest’s perspective, the peasants may appear indifferent to religion. Although they do come to hear mass on Sundays, both morning and afternoon, they refuse to come to confession. Neither penitence nor communion interest them. They are baptized at birth, they confess on their deathbed. This is the extent of their participation in the sacraments.

But they do come to church with pleasure. Unlike the village assemblies, which suffer from absenteeism, religious ceremonies bring out the whole village, rich and poor, men, women, and children. Sunday mass is a community event. Everyone is talking while the children chase each other in the aisles. Gossip is exchanged, business deals are made, young men and women eye each other. The peasants of Sennely come together at their church as often as possible, not only on Sundays but on Saturday afternoons too and on all possible holidays. Their social life revolves around the church, spills over into the village square in front of it, and fills the village inn.

Festivities of a private kind, the drinking and eating that punctuate family occasions such as christenings, weddings, and funerals, do keep the inn busy, but they are dwarfed by the banquets and parades organized by the religious brotherhoods. These are clubs, essentially male clubs, whose religious functions are not particularly well defined but whose social purpose is quite clear: the brotherhoods provide solidarities beyond the level of the family. Within a brotherhood, distinctions of wealth and status are forgotten. Laboureur and journalier sit side by side at the banquets and they march together in the parades of which there can be as many as 100 in a given year. The priest opposes these frequent festivities, but he has no choice in the matter. He is an outsider. His stay in the village is of limited duration. He cannot oppose traditions that are centuries old and much dearer to his parishioners than are the teachings of the Church. Not that the villagers were lacking in religious feeling. They had a particular devotion to the Virgin Mary and they offered up prayers to saints of whom they expected something in return. Their devotions were not quite orthodox in character. They venerated a particular saint as long as he proved effective in warding off illness and other disasters. If the saint failed to keep up his side of the bargain, they switched to another. The priest who lived in Sennely from 1676 to 1710—and whose diary is the source of much that we know about this village—did not care for the villagers’ attitude toward religion. They used the church as a community hall, they showed little respect for the priest and little interest in the sacraments. Even though St. John was the official patron saint of Sennely, the villagers chose to pray to St. Sebastian instead. Presumably St. John had disappointed their expectations at some time in the past. While the priest Sauvageon was in residence, the villagers favored St. Sebastian who was reputed to be effective in curing illness. The most popular social organization in Sennely was the brotherhood of St. Sebastian, to which the villagers were willing to pay dues, although they contributed almost nothing to Sunday collections at church.

Religion played a large part in the lives of the peasants, but it was a religion of their own, designed to satisfy local needs. The priest Sauvageon was constantly irritated and frustrated. Had he wished to play a more active part in the village’s religious life, he probably would not have been allowed to do so. His sense of appropriate piety and observances was too much at odds with local tradition. The difference between the priest’s views and those of the villagers was not necessarily the difference between a rigorous and a lax interpretation of Church customs. During Lent, for instance, the villagers did fast. It is just that they went on fasting past the required number of days. They had their own unshakeable sense of what was right. Their favorite social and religious activities were the processions and banquets sponsored by the brotherhoods. The parades involved the whole village. The biggest of these was on Corpus Christi day, when the village street was covered with hay and straw, the church bells rang, and everyone came out dressed in his finery. The parade proceeded to the neighboring village. On this annual occasion, the public festivities served not only to unite the villagers of Sennely, but also to touch base with outsiders. When the procession reached the neighboring village, all the people of both communities attended mass together, after which they visited the cemetery. No religious procession was complete without the banquets and drinking bouts that wound up the big event as darkness fell.

Having spent some time observing a single village, we should now proceed to ask how representative Sennely may be of rural society in Western Europe. In the Kingdom of France alone, at the time when the records allow a reasonably close glimpse of Sennely, there were about 40,000 villages. In the regions of Western Europe as a whole—those, at least, that we are best informed about, including France, England, Spain, Italy, the Low Countries (modern Holland and Belgium), and parts of western Germany—we may be talking about something like 160,000 rural parishes. Each of these surely had its own character. Even so, we should be able to identify some fundamental traits common to most, if not all, of these communities. We will have to proceed cautiously, in later chapters, moving from the watery Sologne, where Sennely lies, to water-poor Hampshire, glancing at villages in the plains of Lorraine and in the high mountains of the Spanish sierras, including Mediterranean settings filled with permanent sunshine as well as Atlantic seashore villages drenched in rain and flavored by the smell of mussel beds and herring catches. Closing our eyes, momentarily, to sharp variations of soil, climate, language, and religion, we shall listen only to the constants, to the invariable realities that should make generalization possible.

As a starting point, I propose two categories that might serve to make sense of the mass of information we shall encounter. Let us call the first of these categories constraints, the second autonomies.

Approaching the scene from the vantage point of a North American or European society in the twentieth century, any seventeenth-century peasant community must give the impression of being hemmed in on all sides by brutal necessity. We see only the constraints in operation. The historian Gerard Bouchard indicates this in his choice of title: Sennely appears to him as an immobile village, where nothing changes and nothing can change. This may be an acceptable summation, not only for one village but for most, if we restrict our analysis to a few basic aspects of material life.

The population of Sennely does not grow. It cannot grow. If we examine the constraints which keep the population in check here, we will find that they are the very same constraints in effect everywhere else in Western Europe. The obstacle to population growth is an invisible barrier constructed out of the ratio between the land available for cultivation and the hunger of human beings.

This barrier was gradually erected over a period of some three hundred years. It was fully in place by the beginning of the fourteenth century. Before that time, no such constraint had existed. People had been scarce, unclaimed lands plentiful. Immense stretches of forest invited clearing. In this happy situation, the population had quadrupled in size, increasing most dramatically in those regions favored by fertile soil, a temperate climate, and easy access. In Christian Europe as a whole, there may have been as many as 65 million people making a living in the early fourteenth century. This was a high-water mark beyond which growth became impossible. This was especially the case in the most densely settled zones, the heartland of medieval Europe. Some 43 million people, out of a total of 65 million, lived in these favored regions which had been part of the Roman empire: Italy, France, the Low Countries, England, and western Germany. Within this preferred region there were clusters of particularly dense settlement in northern Italy, the Paris basin, and Flanders, where the ratio of people to land reached the level of 40, 50, even 80 to the square kilometer. Forests almost vanished. Churches were separated by no more than half an hour’s walk from each other. This pattern of settlement, established by 1300, was not substantially altered before the eighteenth century. 2

Throughout the four centuries we are concerned with in this book, European peasants lived in a straightjacket of their own making. They had multiplied freely and reached limits that could be breached only at the cost of the gravest perils. When vacant land suitable for homesteading was no longer to be had and every village’s wheat fields and vineyards bordered upon another village’s territory, the margin between survival and disaster narrowed dangerously. With too many mouths to feed and no further expansion possible beyond the customary limits of village lands, efforts were made to increase the grain crop within each village’s boundaries. Timber was felled, swamps were drained, meadows were plowed under. Even poor stretches of gravelly soil and rock-strewn hillsides difficult for the plow to handle were requisitioned when the need for bread demanded desperate measures.

Such tactics merely delayed the inevitable catastrophe. Every one of these expedients was shown to be imprudent in the long run. With the forests gone, timber and firewood disappeared. Every acre of meadowland put under the plow reduced opportunities for grazing. Livestock herds shrank in size. Manure, essential for use as fertilizer, became scarce and the yields of the grain fields, already low in normal times, became even lower. Marginal land put under cultivation barely repaid the investment in seed. Unless new farming techniques could be introduced, to increase productivity, there was only one possible solution to the impasse—and that would have been to reduce the population. Increasing productivity proved impossible. Now the slightest frost, an invasion of locusts, a fever carrying off a few cows sufficed to upset the balance. Chronic malnutrition weakened resistance to disease. Small waves of famine and local epidemics prepared the way for the catastrophic epidemic of bubonic plague which broke out in the summer of 1347, racing northward from the Mediterranean faster than a forest fire. The Black Death, as it came to be known, destroyed perhaps as much as one third of the population within months.

For the survivors, land was plentiful again. Labor shortages were acute. Cattle went untended. Forests grew again. Several generations would be born, would reproduce, would die, before the murderous damages of 1347-48 were repaired. One hundred and fifty years later the population had not yet regained its medieval level. In the course of the sixteenth century, at last, the 60 million mark was passed and growth continued cautiously, shying away from dramatic increases. The pattern set in the fourteenth century was to remain in effect. Population could grow only so much without inviting famine and disease. The most fundamental constraint was now securely in place.

In some measure, the brakes were applied by impersonal forces: viruses, bacteria, rodents, insects, bad weather, the ravages of war. The plague remained endemic until 1721. Other diseases took their threatening turn: syphilis, smallpox, typhus, influenza. But there never was a catastrophe again to approach the scale of the holocaust of 1347. Famine, the great scourge, continued to hover near enough, inspiring fear, a wolf at the door baring its teeth in the dead season. But famines became less threatening in time. After 1700, its pressures became less frequent, less severe, pushed back into pockets of badlands. One cannot escape the suspicion that Europeans had learned to live within the constraints imposed by inflexible harvests. The evidence in Sennely and elsewhere confirms this suspicion.

Sennely, even though cursed with poor grain lands, managed to avoid major famines and epidemics. How? By keeping a low profile, by making sure that its population was not allowed to exceed its resources. The number of families making a living within the confines of Sennely’s territory was not subject to variation. The land could support only about 50 farms. These farms could not be subdivided. Each of them constituted a balanced portfolio of securities, of separate lines of defense: grain, vegetables, orchards, grazing, ponds. Some properties were more profitable than others, but none was abundant enough to overcome the peasants’ caution: the farms had to be kept whole. Any diminution of these units of production was an invitation to catastrophe.

Having more than two or three children would upset the balance. Each generation’s goal was to replace itself without adding to the number of mouths to feed. This goal was achieved by delaying marriage until there was room on the farm for a new couple and their eventual children. The death of a parent activated the son’s or daughter’s marriage. If the new couple proved too fertile, if Fate showed too much kindness to their infant children, so that more than two or three survived infancy, then the parents might well arrange to hire the surplus children out to more prosperous farmers who could use extra help. The larger farms could feed more people than the bare minimum of two adults and two children. It was only because of these larger farms that Sennely could support the landless half of its population, the hired hands, the servant girls, the shepherds who worked for little more than their daily bread.

What we are looking at is an artfully balanced social organization. The men and women of Sennely understood and accepted the limits of their resources and learned to live within these limits. Long ago, when land was plentiful and people scarce, there had been no need for such cautious ways. No doubt the girls had married earlier then and families had been larger. But since the fourteenth century, grim lessons had been learned. Sennely had accepted the new way of dealing with scarcity. Like all the other peasant communities in Western Europe—at least those whose records have been studied so far—Sennely had declared its independence from worldwide, instinctive patterns of behavior. Instead of bearing children as soon as they were nubile, the girls of Sennely accepted the constraint imposed by need. They delayed marriage and childbearing for as long as might be necessary to insure their future children’s subsistence. For some girls that time might never come. They were prepared to conceive only when an offer of marriage was made. Such offers were contingent upon the inheritance of the family land.

Delayed marriage may have been the most important element within the social system created by European peasants after the fourteenth century. It is, in any case, the most readily identifiable one. By delaying marriage, European peasants set a course that separated them from the rest of the world’s inhabitants. As early as 1377, in a very large sample from England, the trend is visible. Of all the girls over the age of 14—and therefore presumably capable of conceiving—only 67 percent were married and bearing children. That proportion would be down to 55 percent in the seventeenth century. Outside of Western Europe, so far as such calculations can be made, the proportion of nubile girls who actually married and conceived would be close to 90 percent. 3 A rough summation of the discoveries made by historical demographers would be to say that European peasants adapted to scarce resources by limiting potential births by as much as 50 percent through unnaturally late marriage and conception. In so doing they bowed to constraints, but they also achieved a degree of autonomy.

AFTER THE BLACK DEATH, by George Huppert; Indiana Univ. Pr., 1998. <

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/asin/0253211808>;