Overriding equals() - a simple solution

Martin Humby 2010

Working with Java Persistence - TopLink and Hibernate, noticed that some of the entity classes generated from database tables by the IDE included an override of the equals(Object) method. Apparently there is some controversy in the Java world about how best to do this and seeing these classes reminded me of a fairly detailed look at this 'problem' from last year.

Opinions are divided into what could be called the Josh Bloch camp - using intanceof to admit objects with the same class and exclude unrelated objects, and the class-comparison camp doing much the same thing but with subtle differences. The vast majority of classes in the standard libraries that override equals use instanceof so we can call this the standard implementation.

In fact there is a trivial OOP solution to writing equals methods that allows further subclassing with or without a new equals that seems to overcome objections from either camp to the arrangement advocated by those of the opposing persuasion - the solution described here.

The original hope was that a way could be found to override equals() that would require no special provision in the superclass. This was found not to be the case but required modifications to the standard implementation are minimal - simply factoring off field comparisons to a separate method and calling this method against the equals() argument rather than the current object. Any possibility that subclasses may be needed appears to indicate use of the simple solution.

The equals() problem

Object's view of equality, no two objects are equal, can be got by comparing base addresses - same-address implies same-object. Otherwise fields, significant from the point of view of comparison, are tested for equality to find out whether two different objects represent the same data item. There is no difficulty in writing a method that compares significant fields when all the objects offered for comparison are the same class. When objects are of different classes things get a bit trickier.

There are three possible equality relationships a derived class can have with its superclass:

1.the subclass declares no new significant fields, does not override equals and instances can be compared with those of the superclass for field equivalence. Such subclasses may carry any number of additional fields that are not significant for determining equality.

2.the subclass declares zero or more new significant fields and overrides equals(): comparing instances with those of a superclass or vice versa always returns false.

3.the subclass declares new significant fields and overrides equals(): instances are comparable with superclass instances when the new fields supply a particular value set, generally nulls or some equivalent - not otherwise in which case comparison must always return false.

Another factor relevant to overriding equals() so it works according to plan is the so-called equals contract in Object JavaDoc. This is a definition of the view of equality that all overridden methods must comply with if the hashed data structures provided by the standard libraries are going to work to contract - a meta-contract if you like.

The most significant of these rules is symmetry: a.equals(b) == b.equals(a) must always be true. If objects comply with symmetry it is going to be fairly hard, although not impossible, to write an equals() that does not comply with transitivity for example. Transitivity problems generally relate to cumulative inaccuracies, which is bad news for comparing floating-point fields but these problems are - as they say, beyond the scope of this discussion.

In general the desirability for inheriting classes in a separate comparison set from an existing class rather than Object is to maintain assignability to references to a common superclass and/or to inherit superclass functionality. The problem dealt with here is that the standard implementation can cater for equality relationship (1) - all classes in the same comparison set, but not (2) - multiple comparison sets. Class-comparison can provide (2) but not (1). Nether can cope with (3).

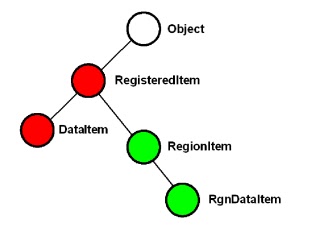

Class names from a particular scenario are used in examples but the scenario is not described in detail. The resulting class hierarchy is shown below:

|

DataItem has a type (1) equality relationship with RegisteredItem in the Red comparison set, RegionItem a type(2) or type (3) relationship. RgnDataItem has a type (1) relationship with RegionItem in a Green comparison set. Type (3) may be considered an unusual requirement but there can be advantages in implementing it when instances of all four classes are to be stored in the same hashed structure: a HashSet for example.

( Readers acquainted with the alternative equals() implementations may now like to skip forward to 'A simple solution'. Otherwise problems with these implementations are discussed below. )

equals() using instanceof

An equals() implementation for RegisteredItem using instanceof might be:

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true; // optional same-object check

if (obj instanceof RegisteredItem) {

final RegisteredItem other = (RegisteredItem) obj;

return (this.itemID == other.itemID &&

this.categoryID.equals(other.categoryID));

}

return false;

}

By making other final we can hope that the compiler will not allocate this local on the stack and generate the assignment but will use the now typechecked reference to obj instead. Otherwise how it works is straightforward: if obj is not null and a RegisteredItem, compare fields for equality, else return false: istanceof includes the not-null check. No provision is made for a situation where categoryID is null and if this field is null in an object submitted to the HashSet a NullPointerException will result.

Think an exception is probably in order when this object's categoryId field is null but if not and we want equals() to return true when itemIDs match and both categoryIds are null the return statement needs to be:

return (this.itemID == other.itemID && ((this.categoryId == null) ? other.categoryId == null) : this.categoryId.equals(other.categoryId)));

RegisteredItems contain only the IDs and details of the server where full data is stored. Updates and new items arrive as ItemData instances carrying the full data set. A new ItemData is put into the HashSet where it remains until data is stored and it is replaced with a RegisteredItem.

When obj is an ItemData it is still a RegisteredItem so proceed as before. As a subclass ItemData inherits the equals() shown above. When this is an ItemData and obj is an RegisteredItem the inherited instanceof check will admit the RegisteredItem object. Using the standard implementation there is no problem, we can simply derive a new class without defining a new equals() and comparison complies with the symmetry requirement of the equals contract.

Note that the equals() method can be rearranged as below with the same effect:

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

if (!(obj instanceof RegisteredItem))

return false;

final RegisteredItem other = (RegisteredItem) obj;

if (this.itemId != other.itemId)

return false;

return (this.categoryId.equals(other.categoryId));

}

An overridden hashCode method is also required for RegisteredItem and this can be got using NetBeans 6.x code completion. (Press Alt + Insert and select hashCode() from the list):

@Override

public int hashCode() {

int hash = 7;

hash = 79 * hash + (this.categoryID != null ?

this.categoryID.hashCode() : 0);

hash = 79 * hash + this.itemID;

return hash;

}

equals() using class-comparison

So why not use code completion to get the equals method for RegisteredItem? Doing this and deleting the redundant curly brackets that don't do a lot for clarity and can nearly double the height of the method, gets:

@Override

public boolean equals1(Object obj) {

if (obj == null)

return false;

if (this.getClass() != obj.getClass())

return false;

final RegisteredItem other = (RegisteredItem) obj;

if ((this.categoryID == null) ? (other.categoryID != null) :

!this.categoryID.equals(other.categoryID))

return false;

if (this.itemID != other.itemID)

return false;

return true;

}

This is the class-comparison approach, quite a surprise when it first appears from code-completion because code generated by the 'Entity Classes from Database ...' wizard with TopLink generates equals() with the standard format. Here the optional same-object check has been omitted but a check for a null argument - implicit to instanceof, is now required. Class comparison rejects any object that is not a RegisteredItem, otherwise field comparisons are done as before.

Unfortunately, this get-it-for-free equals() does not work as required. Problems come up when incoming ItemData objects are compared with RegisteredItems in the HashSet. These comparisons always return false even when fields are equal. Class-comparison rejects an object of any other class and in this case the inherited equals() in ItemData objects rejects RegisteredItem objects in the HashSet.

Such non-intuitive rejection-by-proxy - modified behaviour without modifying a corresponding method, looks error prone to me. Class-comparison provides the second equality relationship with all subclasses doing so whether required or not.

But let's suppose a new scenario requirement is to produce a descendant of RegisteredItem - RegionItem say, that includes a region identifier, significant for equality, and has a similar relationship to a further subclass RgnItemData.

- The standard equals() implementation cannot be used: it works OK in the derived class - superclass instances are rejected, but the superclass equals will accept the derived class. It has no knowledge of new significant fields, will do the comparison based on fields inherited by the subclass and produce a meaningless result.

- Class-comparison cannot be used: in RegisteredItem it will will reject instances of RegionItem as might be required but scuppers the required type-one relationship with RgnItemData.

Fortunately the solution to this false dichotomy between the standard implementation and class-comparison is remarkably simple.

A simple solution

To allow for both inheritance options - overriding equals to get symmetry or not overriding equals and maintaining possible equality with a base-class instance, all that needs to be done is to factor off field comparison to a separate method and reverse the logic in the base-class equals(obj) so that obj calls the method passing the current object.

methods in base-class RegisteredItem:

protected boolean equalFields(RegisteredItem other) {

return (this.itemID == other.itemID &&

this.categoryID.equals(other.categoryID));

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

return (obj instanceof RegisteredItem &&

((RegisteredItem)obj).equalFields(this));

}

instanceof fixes the compared class as the base RegisteredItem, not the type of any class that happens to inherit the method. Classes, like ItemData, comparable with the superclass that do not override equals inherit symmetrical comparison with superclass instances. A class like RegionItem with instances that must never be equal to an instance of the superclass override the inherited fields comparison method to return false.

methods in derived-class RegionItem:

@Override

protected boolean equalFields(RegisteredItem other) {

return false;

}

The derived class then provides the root of a new comparison set: no instance of the superclass or any of its other subclasses will ever get a true result when equals() is called with an argument of this class. Reason - the call goes to the equalFields() method shown above or the comparison is rejected by a new instanceof test in that subclass' overloading of equals().

The equals() implementation used in the derived class is then optional. Code-completion could be invoked to get a class-comparison implementation for example, but to provide the same options for further subclasses, the equalFields format must be repeated at this level:

private int regionID;

protected boolean equalFields(RegionItem other) {

// field comparisons can be in any order - lightest first looks good

if (this. regionID != other.regionID)

return false;

if (! super.equalFields(other))

return false;

return true;

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

return (obj instanceof RegionItem &&

((RegionItem)obj).equalFields(this));

}

This approach requires little beyond what might be done anyway - factoring off field comparisons to improve clarity and facilitate amendments. Its simplicity means that coding errors are unlikely but a few criticisms have been made that I will try to answer here:

You can get incorrect results by calling equalFields directly - don't call this protected method using the same package get-out unless you are entirely confident in what you are doing.

It has sacrificed the simplicity of the canEqual solution for execution efficiency - the solution described here looks much simpler to me; it requires no new base-class methods above those that might be included to improve clarity in a standard implementation and resulting efficiency can only be a plus.

The solution presupposes knowledge of the hierarchy - a knowledge of the class-hierarchy is generally a prerequisite for coding descendants. Using @Override ensures inherited equalFields methods are overridden with a matching signature to return false and not overloaded by mistake.

Any further criticisms would be welcome - can't see any real drawbacks but here is a criticism of my own: code-completion cannot be used to get an equals() with this format. This is true but it can be used to generate a set of field comparisons in a form that can be put straight into an equalFields method without modification.

Equality of the third kind

Another benefit of the approach is that descendants of any class that implements the equalFields format can be coded to have any of the three possible equality relationships with a superclass. The code to implement relationship (3) is only slightly more complex but again readers are invited to skip forward. However, having pulled a scenario out of the hat to use in code examples it looks like the ability to implement (3) could be a real advantage.

A requirement for the third relationship might result if the 'Red' comparison set, shown again below, represents the initial set of classes to be stored in a HashSet. Circumstances change requiring the introduction of RegionItem etc. and life will be much easier if updates to existing items can arrive as either a DataItem or a RgnDataItem with a null regionID. The null is a zero in this case because regionID is an integer:

|

The proposal is to make the Green set not completely separate from the Red set, as it would be using the equals() shown above. Here equals() and equalFields() for RegionItem must do field comparison between all RegionItems and also between RegisteredItems and RegionItems but only if the RegionItem has a regionID of zero.

Looking first at the field equality method that will be called when a RegionItem is the argument of RegisteredItem equals():

private int regionID;

@Override

protected boolean equalFields(RegisteredItem other) {

return (regionID == 0 && super.equalFields(other));

}

Equality for RegionItem against RegionItem tests all fields:

protected boolean equalFields(RegionItem other) {

if (this. regionID != other.regionID)

return false;

if (! super.equalFields(other))

return false;

return true;

}

The RegionItem equals() must now exclude any objects that are not RegisteredItems, call ((RegionItem) obj).equalFields(this) if obj is a RegionItem, equalFields(RegisteredItem) otherwise:

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

if (obj instanceof RegisteredItem) {

if (obj instanceof RegionItem)

return ((RegionItem) obj).equalFields(this);

return equalFields((RegisteredItem)obj);

}

return false;

}

At the risk of obfuscating the code, this equals() can be made slightly more execution efficient by replacing the inner instanceof with an isA (RegionItem), to get rid of the redundant second check for a null argument, and by calling the superclass equalFields() directly:

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

if (obj instanceof RegisteredItem) {

// if obj isA RegionItem

if (RegionItem.class.isInstance(obj))

return ((RegionItem) obj).equalFields(this);

return (regionId == 0 && ((RegisteredItem)obj).equalField(this));

}

return false;

}

Trust me, used as above Class.isInstance does provide an isA, although it may be hard to know that from either the method name or its JavaDoc.

Overriding hashCode() in subclasses

hashCode() implementations produced by code completion introduce a small prime, multiply this value by another small prime and add in a value for the first field. The field value is either an integer equivalent or its hashCode() return if the field is an object. The process is then repeated for any further fields.

Extending this format to derived classes, a 'simple solution' version of RegionItem gets say:

@Override

public int hashCode() {

int hash = super.hashCode();

hash = 83 * hash + this.regionID;

return hash;

}

However, when a derived class instance with null fields may be equal to a superclass instance we need to make sure that under these circumstances equal inherited fields get equal hash codes.

One option is to omit overriding hashCode() in the subclass. Alternatively, null fields in the subclass must result in a zero hashcode contribution and the multiplicative factor be applied to this contribution rather than the inherited value:

@Override

public int hashCode() {

int hash = super.hashCode();

hash = hash + 83 * this.regionID;

return hash;

}

One reason for ensuring that hashCode() is never zero is to allow for lazy initialization and as the cumulative number of fields increases a lazy approach is worth considering. Keep in mind however that String already implements a lazy hashCode(). A final example: a RegionItem of the third kind has grown an additional significant field and implements a lazy hashCode():

private int regionID;

private LocalID localID;

private int hashcode;

@Override

public int hashCode() {

if (hashcode == 0) {

int hash = 79 * this.regionID +

(this.localID != null ? this.localID.hashCode() : 0);

hashcode = 101 * hash + super.hashCode();

}

return hashcode;

}

Afterword

Hopefully equality of the third kind has not obscured the nature of 'A simple solution'. This implementation is simple, very simple, and relies on nothing more complicated than basic OOP. The minimal nature of modifications to the standard implementation makes the simple solution suitable for general use where there is any possibility that a class may need to be subclassed at a later date. It seems strange that it is not more widely used but I have not seen it anywhere other than in my own code and web postings. Any comments would be greatly appreciated.

In Effective Java (Bloch 2008) Joshua Bloch condemns class-comparison in equals() as capable of violating the Liskov substitution principle and supplies examples showing how both the standard implementation and class comparison can be used to get such violations.

In Data Abstraction and Hierarchy (Liskov 1987) Barbara Liskov defines a subtype as one that can be substituted for a supertype without changing program behaviour. Her final conclusions recommend separation of interface and implementation inheritance. Josh is of the same mind identifying composition as a way around the equals problem but his example (page 40) demonstrates another OOP language problem identified by Liskov: broken encapsulation. To maintain encapsulation the aggregated object cannot be exposed as shown and numerous current class methods are required to call aggregated object methods. This work and resulting performance degradation is avoided by the simple solution.

A later paper (Liskov, Wing 1994), identifies object-equality as falling into a class of behaviour 'Nothing bad happens'. Ensuring that nothing bad happens, particularly when code is maintained and extended at a later time, is a major factor in writing real-world applications. To comply with good coding practice the standard equals() method needs to be final and any class using class-comparison should either be final or carry a prominent health warning 'DO NOT SUBCLASS WITHOUT OVERRIDING equals(Object)'.

However, Josh goes on to say, 'There is no way to extend an instantiable class and add a value component while preserving the equals contract, unless you are willing to forgo the benefits of object-oriented abstraction.' The simple solution does provide for extension of an instantiable class with equals contract compliance, which leaves us with 'object-oriented abstraction'.

Using the simple solution, calling contains(RegisterdItem) on a HashSet<RegisteredItem> - if fields match returns true, not otherwise. A RegionItem in the set has an additional field so fields can never match unless equality of the third kind is a requirement. Similarly for calls passing a RegionItem. RegionItems can be introduced with no modification of calls to HashSet methods needed to make things work as before - looks like abstraction to me! In the scenario it is more than likely that other work would result from introducing RegionItem, integration with existing database connectivity for example, but such problems are unrelated to equals() functionality.

Overriding equals() - a simple solution © Martin Humby November 2010 - all rights reserved.

References

canEqual solution [online] Martin Odersky, Lex Spoon, and Bill Venners How to Write an Equality Method in Java http://www.artima.com/lejava/articles/equality.html (accessed 06/11/2010)

Bloch 2008. Joshua Bloch. Effective Java Second Edition Adison-Wesley, © Sun-Micosystems 2008

Liskov 1987. Barbara Liskov. Data Abstraction and Hierarchy. In Addendum to the Proceedings of OOPSLA ‘87 and SIGPLAN Notices, Vol. 23, No. 5: Pages 17–34.

Liskov, Wing1994. Barbara Liskov, Jennette Wing. A Behavioral Notion of Subtyping ACM Transactions in Programmmg Languages and Systems, Vol 16, NO 6, November 1994, Pages 1811-1841

Comments

New comment

Would be utterly wrong to suggest that we override the toString() method and use that?

It would, wouldn't it? But there's something wonderful about...

public String toString(){

return super.toString() + ourChanges;

}

public int hashCode(){

return this.toString().hashCode();

}

public boolean equals(Object obj){

return this.toString().equals(obj.toString());

}

I'm a very bad boy amn't I?

New comment

At 21:13 06/11/2010 Neil Anderson wrote

>Would be utterly wrong to suggest that we override the toString() method and use that?

>It would, wouldn't it?

No, with some limitations it would work fine I think providing toString() reflects all significant fields and no others - similar idea to Radix sort O(n.k) only problem might be execution speed, k is the cumulative length of the string, but if most fields are strings not a lot of difference.

Problems: unless strings for each field are fixed length two unequal objects could have same toString() e.g. "123" + "456" == "123456" + "". If some kind of class identifier is not included totally alien classes can get in on the act. Then, if we are not going to get the same problems as class comparison a getClassID() method is required so it can be inherited by type (1) classes and things probably start to get too complicated but look forward to any further thoughts.

>I'm a very bad boy amn't I?

Wouldn't go that far

OTB Martin