As Lady Hale thanked those who had provided submissions in the UK Supreme Court consideration of the Scottish Parliament's Continuity Bill, she

noted that this case was, “definitely one for the wet towels". This likely means that a

good deal of thought would have to be applied to these vexed constitutional

issues by the Supreme Court justices.

Judgment may not be delivered until the Autumn.

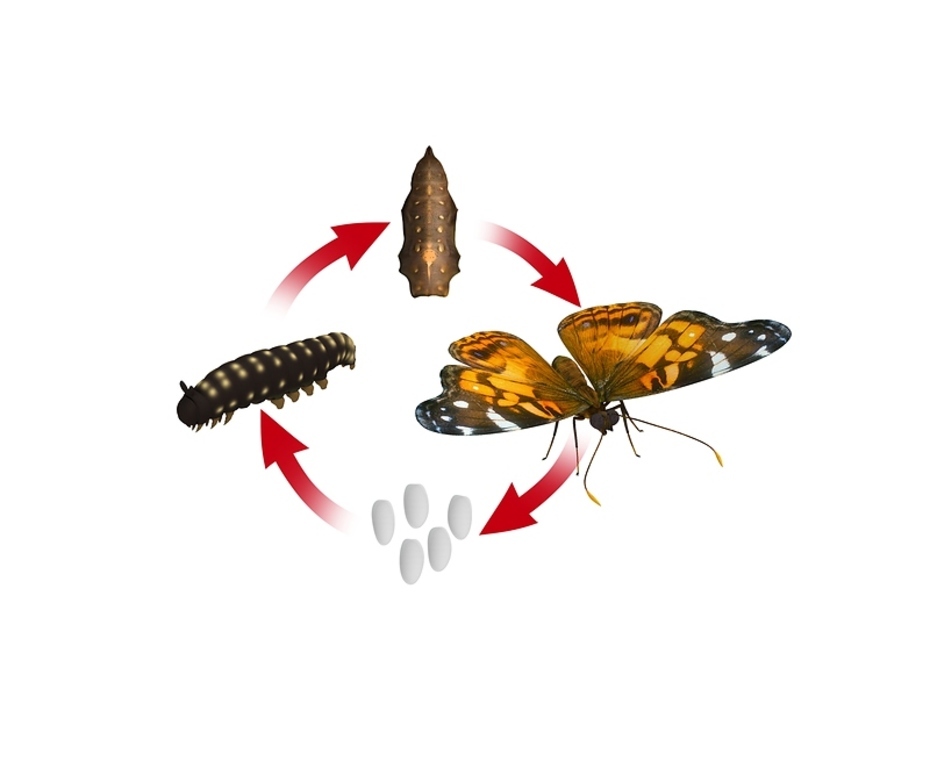

The difficulty of determining which legislative pupae will emerge as 'butterflies' deemed to be within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament and those Continuity Bill provisions which are instead to be considered as ultra vires 'moths' (see previous post) will seemingly be addressed by an agreed Schedule of the contested provisions.

This Schedule will identify whether the provisions are within Holyrood’s legislative competence and will be narrowed down and mutually determined for the Court’s convenience by both the Advocate General for the Westminster Government and the Lord Advocate from the Holyrood perspective.

However, as the tide of EU law goes out, and Westminster and Holyrood seek to determine who should properly have constitutional custody of the accumulated body of EU law - the acquis communautaire - left behind (bobbing on the surface, washed ashore or otherwise sunk) it seems not entirely inappropriate in the circumstances to view the matter of claiming the residual legal control jettisoned by EU law following UK secession as being broadly analogous to circumstances where flotsam, jetsam and lagan in water are claimed.

Flotsam (1871) by L Artan de Saint - with others in this topic from Britannia Images. Flotsam describes things floating on the water's surface. Jetsam is what washes ashore. Lagan is wreckage on the sea-bed usually marked by a buoy.

As the tide of EU law ebbs away the Scottish Parliament will be liberated from one of the restrictions on its legislative competence (Holyrood legislation will no longer need to accord with EU law under section 29(2)(d) of the Scotland Act 1998).

But just what will Holyrood be able to claim as its rightful salvage?

An extremely brief survey of the (Scots) law of property seems to suggest that the Crown (through the Crown Estates Commissioners) has the default claim.

It's worth pausing here to note that this point of property law has some scope to be considered analogous to the rights of 'constitutional salvage'.

Care has to be exercised in trying to make comparisons between distinct fields of law - there is no actual notion of constitutional savage - but the comparison, even if strained - might help understanding.

With that caution in mind discussion can return to property law.

Volume 18 (para. 102) of the Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia (SME) says that “water boundaries are particularly difficult”.

Variables including full sea, flood and spring tides with different land boundaries such as beach or otherwise all make fluid physical boundaries difficult to determine without a considered application of the law.

“In the Land Registration etc (Scotland) Act 2012 (asp 5), 'land' now includes the seabed of the territorial sea of the United Kingdom adjacent to Scotland (including land within the ebb and flow of the tide at ordinary spring tides)” (SME Vol. 18 para.105)

Then there is the instance of things foundering at sea as a result of ship-wreck: The SME later (para. 213) notes: “If at the end of a period of one year from the time when the wreck first came into the possession of the receiver no claim thereto has been established, the wreck will be delivered to the Crown grantee on payment of all expenses, costs, fees and salvage dues in respect thereof”.

Applied to the constitutional context, that suggests that the Scottish Parliament is wise to assert a right of 'constitutional salvage' to those aspects of EU law retained by Westminster that can properly be considered to be aspects of devolved competence.

Statute law has impacted upon - or solidified in legislation - the pre-existing common law that dealt with things jettisoned following a watery break-up. “Detailed rules for the administration of wreck are contained in the Merchant Shipping Act 1894…[Although there is no express exclusion in Part VI (ss 67–79) of the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982, it may be assumed that the provisions of that Part as to the disposal of lost and abandoned property are not intended to apply in the case of wreck].”

Loss of the Brig Vine of Bristol off Whitby (Britannia Image quest)

The Merchant Shipping Act 1995 now also addresses pollution. It may be that there are issues within retained EU law over which neither Westminster nor Holyrood will wish responsibility.

There is also an interesting case from the House of Lords, between the two World Wars, concerning the wreck of the brig Elizabeth that might speak to the likelihood of the UK’s membership of the EU being salvageable now that Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union has holed the UK’s EU position in the great continental convoy below the water-line:

"The Elizabeth , a brig, sailed from London in June, 1818, on a voyage to St. Petersburg and back to Portsmouth. She arrived in due course at St. Petersburg, and, having loaded a cargo of hemp and deals, she sailed thence on her return voyage to England on September 25. On September 27, "without the default of any person," she ran on to a reef of rocks near the Island of Gothland…

Here was a ship that had encountered what the law might call a semi-naufragium - full of water, as they themselves [that is, the seamen] state, so that they could not live on board. She is put into the hands of foreign carpenters for the course (a protracted course) of necessary repairs. It was doubtful whether she could at all receive such repairs as would restore her to a navigable state. It was by no means doubtful that she could not receive such repairs as would enable her to proceed till after the approach of spring in that climate had restored the seas to a navigable state, so as to allow her a passage."

Barras Appellant; v Aberdeen Steam Trawling and Fishing Company, Limited Respondents [1933] A.C. 402