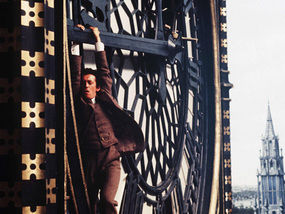

"It had been a close shave,

but I had been in time".

Judgment in Case C-621/18 Wightman and Others v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union has followed the Opinion of the Advocate General, though with slight nuance.

The nuance a little below but the main thrust of the judgment distilled to its essentials is:

“[G]iven that a State cannot be forced to accede to the European Union against its will, neither can it be forced to withdraw from the European Union against its will.” (para. 65).

Interestingly this refers to the 'will of the state' yet in the preceding paragraph, the focus falls upon individuals:

“It must also be noted that, since citizenship of the Union is intended to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States (see, to that effect, judgments of 20 September 2001, Grzelczyk, C‑184/99, EU:C:2001:458, paragraph 31; of 19 October 2004, Zhu and Chen, C‑200/02, EU:C:2004:639, paragraph 25; and of 2 March 2010, Rottmann, C‑135/08, EU:C:2010:104, paragraph 43), any withdrawal of a Member State from the European Union is liable to have a considerable impact on the rights of all Union citizens, including, inter alia, their right to free movement, as regards both nationals of the Member State concerned and nationals of other Member States.”

This brushes up against a constitutional conundrum without resolving it: The contested notion of the ‘will of the people’ and the true consequences of a public debate that has, at least partly, been shaped by interests that may not always align with the interests of either the state or the its individuals.

That is not to say that state interests are not well served. However it may not be the interests of the UK or its fellow EU member states but the interests of states outside of the EU that are best satisfied. Equally, the self-interest of a few influential individuals (whether economic or political) must be distinguished from individual interests (such as inure within EU citizenship) more widely. Andy Serkis's recent depiction of Kipling's Jungle Book portrays such competing interests in a very entertaining, if chilling, way.

At risk of making this blog even more like a penny novelette this part of the Court's judgment reminds me of the moment in John Buchan's Thirty-nine Steps when Richard Hannay bursts into Sir Walter Bullivant's home sanctuary to warn him of the 'Black Stone' organisation as Hannay suddenly realizes what is at stake:

"The door of the back room opened, and the First Sea Lord came out. He walked past me, and in passing he glanced in my direction, and for a second we looked each other in the face. Only for a second, but it was enough to make my heart jump. I had never seen the great man before, and he had never seen me. But in that fraction of time something sprang into his eyes, and that something was recognition. You can’t mistake it. It is a flicker, a spark of light, a minute shade of difference which means one thing and one thing only."

But back to the nuances within the main thrust of the Court’s judgment:

A return to the status quo ante

It is made explicit that if a member state chooses, following Article 50 notification of withdrawal, to reverse its decision, pre-existing conditions of membership are not affected.

This is an enormously significant aspect of the judgment. It was not at all certain that this would be the case and it could have been that membership following a reversal from article 50 notification would be based on revised terms. The Court's reassurance here is important.

Tempus fugit

However the Court’s judgment has a little more 'chronological urgency' than the formulation provided by the Advocate General.

The Press Summary notes: “ That possibility exists for as long as a withdrawal agreement concluded between the EU and that Member State has not entered into force or, if no such agreement has been concluded, for as long as the two-year period from the date of the notification of the intention to withdraw from the EU, and any possible extension, has not expired."

The dispositif:

“Article 50 TEU must be interpreted as meaning that, where a Member State has notified the European Council, in accordance with that article, of its intention to withdraw from the European Union, that article allows that Member State — for as long as a withdrawal agreement concluded between that Member State and the European Union has not entered into force or, if no such agreement has been concluded, for as long as the two-year period laid down in Article 50(3) TEU, possibly extended in accordance with that paragraph, has not expired — to revoke that notification unilaterally, in an unequivocal and unconditional manner, by a notice addressed to the European Council in writing, after the Member State concerned has taken the revocation decision in accordance with its constitutional requirements. The purpose of that revocation is to confirm the EU membership of the Member State concerned under terms that are unchanged as regards its status as a Member State, and that revocation brings the withdrawal procedure to an end.”