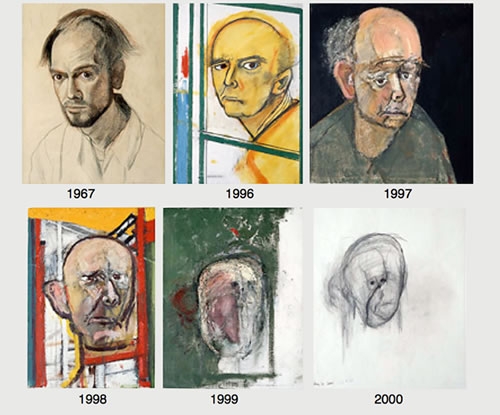

Anyone with any sensitivity to art could not look upon these images and remain unaffected by it. Painted between 1967 and 2000 they are self-portraits by American born artist, William Utermohlen, and created at a time when the ravages inflicted upon his brain by Alzheimer's disease were already such that his work tangibly manifests his dwindling capacity to externally reflect upon and render his sense of self. The paintings and drawings stop in 2000.

“He died in 2007, but really he was dead long before that," explains the bright-eyed woman to a room full of sympathetic listeners. "Bill died in 2000, when the disease meant he was no longer able to draw.”

This painting was one of a series presented by Utermohlen's widow, Patricia Utermohlen, and Dr Shelley James at an Urban Times supported event held in the GV Art Gallery, London on 26th January 2012 as part of the Trauma series.

The press notes for the event explain the nature of the exhibition and seek to contextualise Utermohlen's work. While the paintings undoubtedly function as an artistic and artifactual record of the artist's tragic decline into cognitive oblivion, they also serve a role as medical documentary evidence that might contribute to some advance in understanding the aetiology of Alzheimer's:

Doctor Rossor’s team and his nurse Ron Issacs encouraged him to continue drawing and portraying himself. The last self portraits painted between 1995 and 2001 are unique artistic, medical and psychological documents. They portray a man doomed, yet fighting to preserve his identity in the face of an implacable disease encroaching on to his mind and senses. With perseverance, courage and honesty the artist adapts his style and technique to the growing limitations of his perception and motor skills to produce images that communicate his predicament.

The series of paintings created between 1967 and 2000 - and especially those from 1996, painted within a year of the initial diagnosis - record with frightening clarity the dreadful, inexorable destruction of a mind. The last image, drawn in 2000, is almost too painful to regard. It's as though for one final, vanishingly small moment Utermohlen was able to see and know himself for one last time before the blackness overcame him.

I wasn't at the event itself, but a reviewer for the New Scientist, Andrew Purcell, was and his words echo my own horrified realisation of what Utermohlen must have endured before he succumbed to nothingness.

"That Utermohlen was able to continue with his art as his disease progressed amazed the evening's final speaker, Stephen Gentleman, neuropathologist at Imperial College London. “It’s astounding,” he says. “Utermohlen just shouldn’t have had the mental ability to be able to carry on doing these as long as he did.”

"Then came the bombshell - the words that stuck with me and played over in my head as I lay in bed later that evening: “It sounds awful,” Gentleman told me, “but in cases like these, you really hope that the patient themself loses understanding as quickly as possible, because to be in a body whose brain is failing and still have insight into what is going on must be simply horrendous.” The works on display indicate that Utermohlen did not have even this small mercy."

Tragic and unsettling though Utermohlen's final paintings are, when one looks beyond the bleakness of his fate what comes through is the realisation that creative expression and the capacity and overwhelming drive to create, to record and to leave some tangibly unique testament to one's existence appears to be so strong, so primordial and so intrinsic to the human condition that it is metaphorically hard-wired into our brains. And it's only when Alzheimer's has finally wrought its ultimate necrotic havoc and the creative light flickers out that we can reluctantly face the painful reality that while the body might continue to survive, beyond any shadow of doubt, the light of a mind has been forever extinguished.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Jeremy for bringing this to my attention.

New Scientist, Culture Lab: Self-portraits of a declining brain

William Utermohlen's official website

Urban Times - Art & Alzheimer's

Comments

New comment

This post touched me, thanks.

One of my very best friends is slowly being lost to Alzheimer's. Occasionally there is humour to be found, but mostly it's frustration my end which results in guilt, and the gradual mourning of the life being lost to the disease. It makes me very sad if I dwell on it for too long.

New comment

Thank you for your thoughts, Rosie. I lost my grandmother to dementia - though any medical distinction between Alzheimer's and dementia is largely irrelevant when essentially they both lead to the piecemeal disintingration of a person one once loved.

I look upon these paintings and my first response is probably something closer to fear than sadness. If I dwell longer I can see the tangible evidence of a sheer force of will of the human spirit at work and knowing that we are all mortal, I guess that is a positive.

But ultimately, above all, I simply hope I never have to face the same fate.

New comment

Am glad I saw Rosie's post before commenting, because I didn't read the text first off......I was going to say that I think your portraits Clive are better (in my eyes) than the famous artist here....well I still think that, but now I know the story....and i was going to say that out of those portraits it's the 1996 one that I think/thought was the most compelling to view, and that is the year he was diagnosed.New comment

Hi Clive..Anthony here..The portraits are sad..but the very last one is devastating..this destruction of self..there is nothing of the mind left just an empty space..its very abstract..almost as if he is dissolving before our eyes..very important piece..Thanks for putting this up and I will now keep an eye on Urban Times for more ..Oh..and I also have been following your work..very good(although I'm more Mondrian than Freud these days)..be well..AnthonyNew comment

Emily - thank you for your supportive comments, I'm touched. (My mum would say that I've been touched for years!). I see what you mean about the first portrait done in the year of his diagnosis - there's a real stripping back to the essential elements. Powerful.New comment

Hello Anthony; yes, I very much agree with you on that last image, it really is like he is dissolving in front of his (and our) eyes. From Freud to Mondrian - that's quite a journey!

Clive

New comment

This is so vivid isn't it? and somehow, for me , creativity is always such a positive thing so i cant make up my mind whether its positive 'cos he was still using his skills , or not 'cos the creativity seems so gnarled.

But it makes me feel damned lucky that i can do so many things still and will keep thinking positively .....things like this always make me resort to selfish thoughts, but thats ok, i share them around afterwards!!

Have you done any more paintings/drawings?

Gillian

New comment

Gillian - I know what you mean about feeling lucky in regard to these sorts of tragic twists of fate.

As it happens, I've started another effort, but it looks like I'll have to put it on hold as I've now got to mark a whole bunch of TMAs!

Stay tuned.

New comment

Good morning. How is your painting/drawing coming along? Or are you still marking TMA's?

I'm doing my 3rd assignment at the moment, it's sheer luxury-I have to write poetry and I'm loving it. I'm not sure my very helpful tutor will agree with me though.

Gillian

New comment

Hello Gillian, still marking - phew! they're taking for ever. In the meantime, I've put a new post up that you might like. Not my work, I'd hasten to add!