Regards: McAndrew, P. & Farrow, R. (2013) ;Open Education Research: from the practical to the theoretical' in McGreal, R., Kinuthia, W & Marshall, S. (eds.) Open Educational resources: Innovation, Research and practice Vancouver, Commonwealth of Learning & Athabasca University, pp. 65-78.

Consider the following questions:

How would you judge OpenLearn in terms of your definition of innovation?

I consider my definition of ‘innovation’ to be still emerging out a cluster of issues that, at the moment don’t yet have, for me, clear boundaries. I suppose the nearest I get to it yet is: ‘something in the process of changing where the product is not yet fully known.’

I think that is why innovation is as likely to raise anticipatory fear as well as anticipatory pleasure. I think it is also why people, I include myself here, sometimes resist change. I suppose I believe that any ‘change’ worth the name isn’t innovation unless it provokes that resistance. That isn’t to say that the resistance is of anxiety. Sometimes it is formed from a kind of denial: ‘nothing new there ….’, ‘nothing new under the sun …, ‘yes, we’ve seen it all before…, and the belief (which often survives despite contrary evidence) that all change is cyclical. These are the myths about innovation that create stasis – or worse, stagnation. The most conservative thinkers are not against change: Lampedusa in The Leopard has his Sicilian Prince advise his heirs: “If you want things to stay the same, things will have to change.’

And I think change is also something with multiple meanings – to different people (and sometimes to the same person in a form of ambivalence). That is why I think we can’t really define ‘change’ without having multiple perspectives that might be those of the stakeholders involved in the change. That is more difficult than it seems because sometimes changes reveal, or even create, new stakeholders in the process and its products. This has been happening in the NHS for some years – to effects that are not all good. We can only regard the Open University as new and innovative if we disregard the conservative resistance and denial of the value of digital innovation of some of its institutions, professional role-bearers and people (of course not all).

All of these stakeholders will perceive and assesses (and possibly be effected) by ‘innovation’ in different ways and this is one reason for the difficulties of bringing change about collaboratively without it being fundamentally robbed of its central intended meanings. This happened to social work reform in the 1990s.

I think McAndrew and Farrow suggest that OER is a kind of cultural object, whose meaning and potential is yet unfixed, other than in rhetorical hype (see sentence 1). Its meaning is not in what it is or does but in its ‘attractive affordances’. It is something as yet unrealised as product or process, both of which contain imponderables, a potential for re-visioning the roles, relationships and practices of an organisation, group or person. Hence for me the key stage is the sixth (‘Transformative: change ways of working and learning.’)

In education this has an effect on issues of identity, authority, power and, of course, the distribution between stakeholders of rewards. Think of the real revolutionary effect of fundamentally changing the relationship of learner and teacher, the employment of bot devices (Bayne 2015): ‘Any teacher that can be replaced by a machine SHOULD be replaced by a machine’ (for reference see the blog on Bayne 2015 below). I think this is why McAndrew and Farrow disappoints a little – positivity about ‘growth’ and ‘progress’ forgets to point out that these processes are necessarily complex with many facets: quantitative, qualitative or occurring internally or externally to the changing thing. That is why the debate in the OU can seem rather unsatisfactory. What looks like a massive amount of external change may not be even perceived within some of the institutions internal agencies. I remember once making a suggestion for reviewing the access to discussion forums between learners and Associate Lecturers. The outcry was so phenomenal from other ALS, my suggestion was shut down only weeks after it went live, with a minus score that would challenge greater ‘losers’ than I to prove themselves.

For me the great untested element in this paper is the assumption that the ‘potential of OER to act as an agent of change’ can be realised without those changes being end-stopped by resistance. The paper talks of a pilot that cannot be expected to test the longevity and uncertainties of emergent forms.

What key challenges facing the OER movement can be dealt with more quickly than others?

Of those listed on p. 68, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 11 are relatively easy to provide and positively adopt. But changing the control of teaching/learning and assessment/evaluation design will meet resistance from paid professionals and their unions and threaten promotion or adoption, or fundamentally disempower the innovation’s potential to project into future renewal. This is in part for reasons mentioned above.

How do open educational resources challenge conventional assumptions about paying for higher education modules?

This relates to the issue of distribution of costs and benefits between stakeholders in education. The tendency, even in ‘empowerment’ models of teaching has been to increasingly shift the ‘costs’ of education to its consumer (not least in this new term for learner). Thus teaching has become, in defence of its right to maintenance of financial and other rewards, increasingly polarised from learning as either a process or product, in favour of models of the necessity of control and authority. There is something to this argument but it can be answered by innovative learning design which distributes costs and benefits somewhat differently. The control role of accreditation (p. 74) in maintaining teacher and institutional authority is the hardest nut to crack I think and perhaps one where certain key stakeholders will recognise no debate worth having. When I taught in a university, one teacher was reported, by learners to me as then subject head, to have told his groups: ‘remember I mark your assignments.’

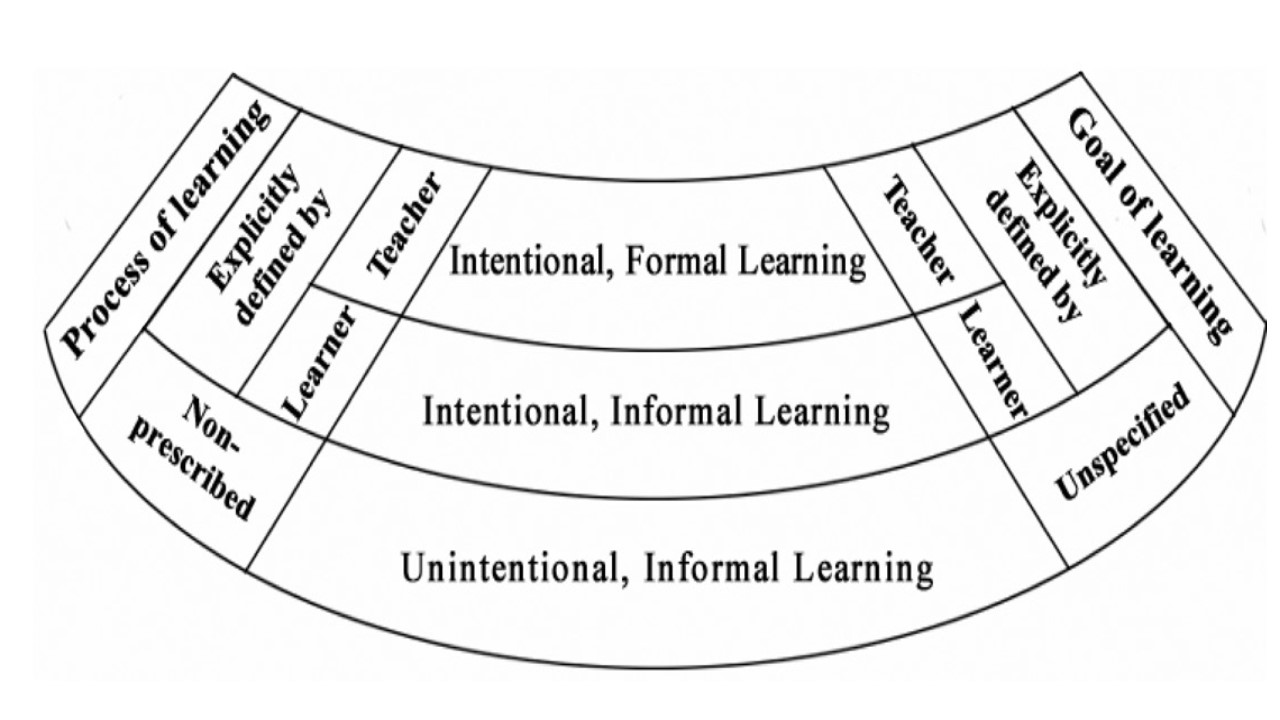

Vavoula’s useful model, which finds

a place for what we use to call the ‘hidden curriculum’ – in the formally

unspecified and non-prescribed. This is where the values of any ideology can

subsist, but especially those who claim, like the ‘open market’, that they are

not ideological. It doesn't take a Zizek to disprove this.

Vavoula’s useful model, which finds

a place for what we use to call the ‘hidden curriculum’ – in the formally

unspecified and non-prescribed. This is where the values of any ideology can

subsist, but especially those who claim, like the ‘open market’, that they are

not ideological. It doesn't take a Zizek to disprove this.

All the best

Steve

Comments

New comment

I read this post with enormous interest on the eve of the 3rd iteration of the School for Health and Care Radicals, a NHS-led initiative to bring about purposive change in the field. Your post has made me reconsider this OER as a cultural artefact as much as an agent of change. Very thought provoking and impactful. Thanks Steve.Victoria