West (2018)[1] writes:

Writing about architecture takes several approaches, and it is important to distinguish between them. These can be summed up as a connected trio:

· history

· theory

· criticism.

Few individuals can combine these three approaches, although knowledge of each must inform the output for any one of them. Be careful that you understand the difference between writing a historical account and writing a critical assessment of a work. TMA 03, for example, does not ask you to assess the success or failure of a work.

As a learner, I find that unhelpful. The point seems to be

that I am warned from assessing ‘the success or failure of a work’. It is hard

to see that anyone approaching even the bare title of TMA03 would make this error.

To remind ourselves the title, without the long tail of its ‘guidance’ and ambiguous

references to Susie West’s thoughts in section 4, of which the above is an

example, is:

Part 1

Draft a preliminary literature review incorporating an outline of possible research questions and themes. (1000 words) (34% of your mark).

Part 2

Write up 2–3 of the research themes for your chosen case study. (2000 words) (66% of your mark).

Where therein is an invitation to ‘assess the success or failure of a work’.

And then there is the ‘connected trio’. The warning not to combine these seems also quite leading, as being more than advisory: perhaps threatening failure in the task. What trait, that West imagines to characterise postgraduate learners? I imagine it can only be that such learners might so far outreach themselves as to think that they can aspire to challenge the categorical assumptions she makes about history, theory and criticism. We are to believe, for instance, that distinguishing history from theory is totally possible: that history could be (and should be if that learner know what’s good for him/her) conceptualised a-theoretically. West elides the obvious problems here by choosing to warn us off ‘criticism’ rather than theory, else she would have had to have written:

TMA03 for example does not ask you to investigate the theoretical frames that support the work you are studying.

This would be self-evidently nonsense, since a literature review and exploration of themes at Master's level would clearly be enhanced by some sense of the theoretical approach to history the work will take.

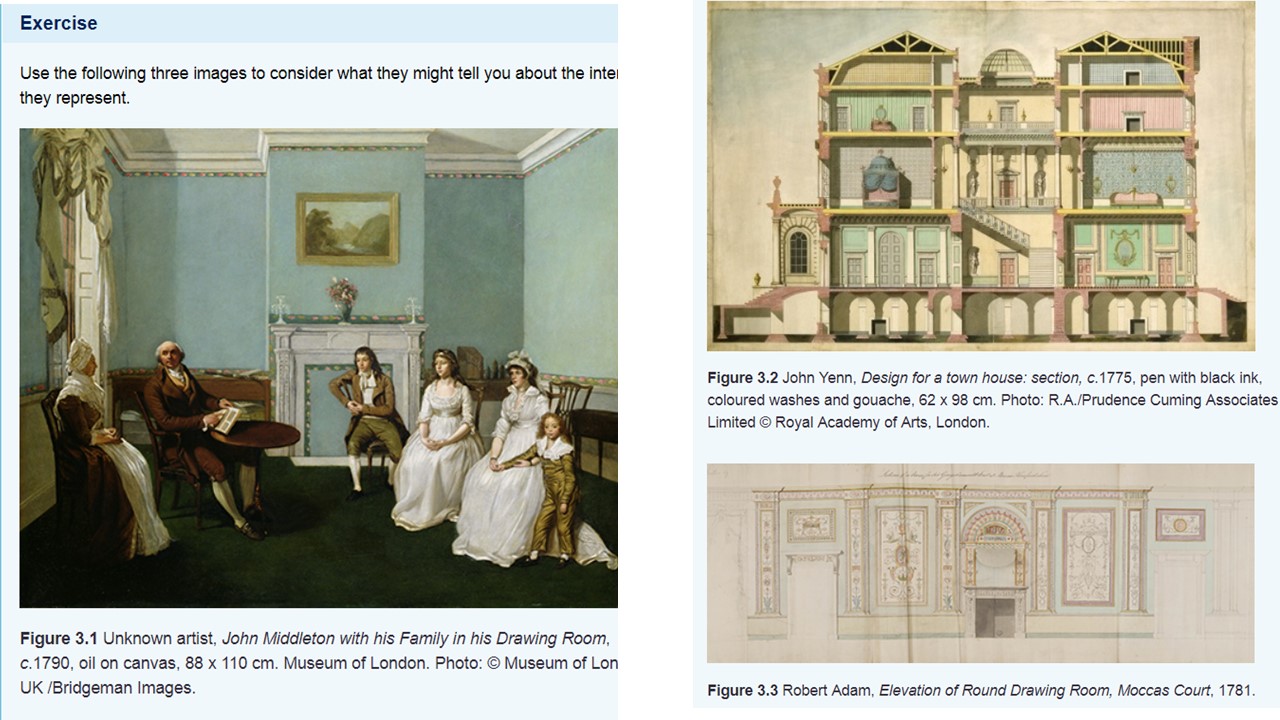

My problem is that, as one of the learners receiving such instruction, it feels appropriate to me to approach the notion of an ‘interior’ precisely through both history the act of capture of the phenomenon in consciousness. We start with the senses, of course, but all the senses in concert and in the light of the body’s sense of space (proprioception). In turn those interact with the cognitive-affective perceptual systems that combine with senses in perception moving both bottom-up and top-down.

And this can be historically validated. Consider a ‘room’ or other space in Woolf’s fiction for instance. Mrs Ramsay apprehends those spaces as knowable only in relation to consciousness. Mrs Ramsey in To The Lighthouse apprehends a room only in terms of the intentional force of her consciousness in shaping it. As the dining-room door is held open for her:

It was necessary now to carry everything a step further. With her foot on the threshold she waited a moment longer in a scene which was vanishing even as she looked, and then as she moved … and left the room, it changed, it shaped itself differently; it had become, she knew, …, already the past.[2]

An interior space here is in fact a ‘time-space’ known only

in relation to the body that moves through it and is agentive in its shaping in

doing so. This could be claimed to be ‘theory’ but it is also ‘history’ since

it involves direct apprehension of the passage of time. For me this can, and

would, shape one’s response to interiors as designed and shaped, and continually

re-configured by the act of living bodies moving through them and moving ‘things’

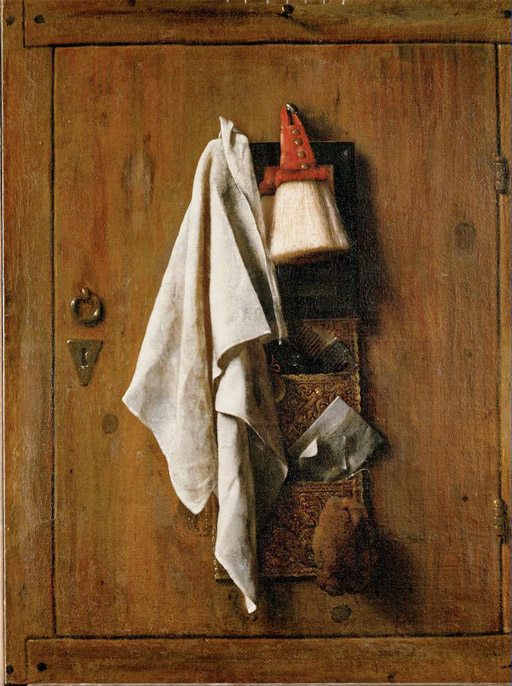

within them, like doors, tables, fire-screens, room-screens, furniture,

ornaments, paper or paint coverings ……

Hence my interest in phenomenology. But while my interest rises, Susie West haunts me with her strictures of over-reaching, of thinking too much for myself, of departing from a template. But taking even a basic definition of phenomenology, its use is apparent:

Basically, phenomenology studies the structure of various types of experience ranging from perception, thought, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, and volition to bodily awareness, embodied action, and social activity, including linguistic activity. The structure of these forms of experience typically involves what Husserl called “intentionality”, that is, the directedness of experience toward things in the world, the property of consciousness that it is a consciousness of or about something. According to classical Husserlian phenomenology, our experience is directed toward—represents or “intends”—things only through particular concepts, thoughts, ideas, images, etc. These make up the meaning or content of a given experience, and are distinct from the things they present or mean.[3]

To study these things is NOT, as West

suggests, to seek to know Duncan Grant’s, or Vanessa Bell’s, intention in

creating the interiors they did – in shaping space, light, lines and pattern

etc. It is to research how meanings in the cognitive-affective realm, overdetermined

almost certainly by the socio-cultural semiological-domain, shape and reshape sense perception and

Husserlian ‘intentionality’ of that we call, once apprehended, an ‘interior’.

That is to say that the placing and decoration of a mantelpiece is not immune

from the meanings associated with the ‘fireplace’ or ‘hearth’ it surmounts. It

is even less immune from meanings of hearth that helped co-shape notions of

family, subjectivity and collectivism that are part and parcel of the things

assembled to make up interiors.

This is a personal argument but it feels urgent. To learn is to adventure but it ought not to be to accept over-prescription. Educators can lead but they can’t determine – that is a much more complex cooperative endeavour between persons, and including autonomous learners, objects and their intersecting agencies. I feel as if I becoming drawn into Bruno Latour here – but let’s leave it there. Course leaders in the history of art have to empathise with learner aspiration, in as far as this is confined to learning and not ‘grades’, and not put up barriers, whose sole purpose is to lower expectations of not only learners but learning as the intentionality behind the existence of institutions like the Open University.

[1] West, S. ‘The Scope of Architectural History’ in A844 Block 3: Section 4 Research issue: researching architecture. Available at: https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=1312044§ion=3 (accessed 10/02/19)

[2] Woolf, V. (1964 Penguin Ed.) To The Lighthouse, Harmondsworth, Penguin, p.128

[3] Smith, David Woodruff, "Phenomenology", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/phenomenology/>;.