This is Fig.1 from Scanlon et. al. (2013:29)

This is Fig.1 from Scanlon et. al. (2013:29)

Coketown University Report.

Introduction.

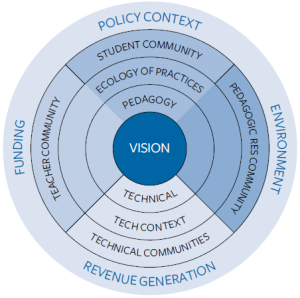

The long-term goal of senior managers at Coketown is to ensure that it can state and provide evidence that ‘learning and teaching at this institution are supported by learning analytics (LA)’. It equates this aim with a vision for the development of LA that can be carried forward into future goals, even ones as yet unknown. This is visionary because LA does not only aim to support teaching and learning but to uncover data that enables its transformation moving forward. This is why Fig 1 above has VISION at its centre.

This report, without denying the value in potential of that vision will argue that no single and unitary process of holistic change is likely to be possible, and that the immediate aim should be to state that ‘learning and teaching at Coketown University is being currently transformed by an active and ongoing process that will aim to build its future with the fullest support of LA. That process of transformation is shared and ‘owned’ by the university’s staff, learners, partners and funders ensuring that change occurs within a sustainable and stable framework.’

The problems raised by change

Even when senior managers express a vision with conviction, integrity and in the best interests of all stakeholders in the pedagogic enterprise, they have to face the realities posed by change, especially in an institution with the history and well-earned pride as Coketown.

That reality can be expressed in terms of seeing the core elements of the practices which support vision in terms of the strong communities which engage these practices and a long history of having successfully done so, We can (as in Fig. 1), express the university’s practices under 3 headings of practice necessitated by maintain and sustaining the university over time:

1. Policy creation, update and revision

2. Management of the Environment (including a wide range of resources from buildings, open or dedicated spaces and core equipment).

3. The generation and maintenance of revenue in terms of the relationship between the university’s income and expenditure, including non-returnable funding from partners in government, business & the 3rd sector (I have chosen not to make these appear two headings as might be suggested in Fig. 1).

Under this mantle exist 4 communities of variable distinctness. Some of the changes we envisaged involve working with current best practice of successful and evidence-based interactions between these communities and supporting their semi-independent growth outwith the constrictions of a single vision.

These elements of co-produced change will form the patches of the bricolage which will build to our ultimate vision.

At base these communities are those based in pedagogical and technological practice.

1. Pedagogical communities with different traditions and structures (and sometimes apparently different goals) include:

1.1. The Student Community, with a clear stake in successfully applied pedagogical practice, which we have found to be best supported by involvement in those practices.

1.2. The Teacher Community, sometimes divided into subject-discipline departments with different traditions but a common aim. Our aim is to build on that commonality.

1.3. The Pedagogical Resource Community, including administrators, rooming, catering as well as educational equipment. And;

2. The Technical Communities, often apparently operating in (what appears to others) an impenetrable world of technological knowledge, skill and linguistic exchanges. Thus while we often speak of an ‘ecology of practices uniting the pedagogical community, the context of technology is in practice often seen as remote from those practices – a fact revealed in Macfayden & Dawson’s (2012:157) finding that in one sister university 70% of teaching staff made no use of the university’s LMS.

Clearly one major aim is to bring the technical context within the embrace of the ecology of practices that currently sustain community alliances in Pedagogical matters. This is easier envisioned than brought about and we see change as occurring piecemeal (or so it might appear) but under the aegis of a persistent intent to turn co-construction of new practices (and the community alliances involved) under one umbrella.

In the mean-time, though our umbrella may look to the aspirant like a leaky patchwork, we endeavour to achieve stability in stages (often uneven stages, of discrete development overseen by senior managers. This is the process Scanlon et. al. (2013:33) call ‘bricolage’. When ‘vision’ appears to everyone except senior managers as a potential imposed ‘nightmare; we agree with Scanlon et. al (2013:33) that:

Vision often emerges and evolves through exploration, through networking and through active engagement in research, development and educational practice.

RECOMMENDATION

Hence our recommendation that policy and advertising material bear the statement:

‘Learning and teaching at Coketown University is being currently transformed by an active and ongoing process that will aim to build its future with the fullest support of LA.

That process of transformation is shared and ‘owned’ by the university’s staff, learners, partners and funders ensuring that change occurs within a sustainable and stable framework.’

One example from our current ‘bricoleur’ activity is the Life-Long Learning Advisory Project, PEAR.

All I can do for now.

All the best

Steve

Macfayden, L.P. and Dawson, S. (2012) ‘Numbers are not Enough. Why Learning Analytics Failed to Inform an Institutional Strategic Plan’ in International Technology & Society, 15 (3), 149 – 163.

Scanlon, E., Sharples, M., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Fleck, J., Cooban, C., Ferguson, R., Cross, S. and Waterhouse, P. (2013) Beyond Prototypes: Enabling Innovation in Technology-Enhanced Learning. Technology-Enhanced Learning Research Programme; also available at http://beyondprototypes.com/ (accessed 15 June 2016).

Comments

New comment

Thanks Steve, this blog has helped to shape my thinking on this task.