There is anxiety among feminists, both those questioning and those supporting transgender politics. Transgender activists find comments from feminists questioning their identity particularly confusing and upsetting (compared to the expected critique from right wing thinkers), as the struggle for transgender equality is based in the feminist movement and thinking. Feminists feel that a gender identity they have fought hard to establish as strong and positive in the face of continual and ongoing patriarchal violence and backlash is undermined in the rise of ‘queer’.

Here I will explore some of these issues through my personal memories of gender and sexuality in the 1990s London scene, and academic thinking on gender identity. I hope to offer tools and insight about the positions both sides are taking. Using ideas about hetero-patriarchy and an ‘economy’ of sexuality, I hope to clarify what is at stake for each of these sides in a new ‘sex wars’.

The 'Sex Wars' and other history.

I was startled and felt kinda old when I read about the ‘sex wars’ in books and realised that this had become history! The ‘sex wars’ could be seen as a fore-runner to the current transgender debate. This was an intense debate in metropolitan lesbian circles in the 1990s, when feminist lesbians turned our backs on standard male/female role models. The classic butch/femme identities in lesbian culture were widely questioned. I and my friends sought to dress in androgynous outfits (we couldn’t afford glamourous new clothes anyway!). One gay guy pal remarked to me: “But why do lesbian women have to dress in such an unattractive way?” and we both laughed as he went on: “I suppose you don’t want to attract men.”

Later I was to realise that my own identity is high femme. I find it affirming and enjoyable to dress in exaggerated feminine style. (I used to say I was a drag queen in the wrong body.) I recently posted a meme from Some Like It Hot on our office internet chat board, saying I was going to practise walking up and down my hallway in heels as I wanted to look more like Tony Curtis coming out of lockdown than Jack Lemon.

LGBTQ people can now choose from many more diverse ways to express ourselves and are not expected to represent our politics in an Epistemology of the Closet (Sedgwick, 1990). It seems absurd now that back then we were saying ‘Thou shalt not dress’ in any way at all, but in that time of political repression (I am old enough to remember Section 28 being brought into effect, as well as being repealed) everything was a gesture at attempts in the broader discourse to control us. Insisting that we existed was a political act that brought violence in response. I remember pictures of Adam and Steve on one Australian Pride float in a retort to right wing Christian groups who would hold up posters saying ‘It’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve’. People like Harvey Milk paid the ultimate price for being publicly out as gay. This activism followed feminist protest in the 1970s, marching in the streets to ‘take back the night’ after being told that if we wanted to be safe from rape and murder, we should stay at home.

On the London scene, I remember ideological debate exploring the way that two women living together were economically disadvantaged, while two men usually had much better household incomes (DINKies – Double Income, No Kids). Lesbian separatists would refuse to talk to bisexual women, as being traitors to the cause. Lesbian women who accidentally fell in love with a gay guy pal were castigated and banned from friendship groups, as if their choice of partner meant they could no longer think clearly about feminism or gay rights. The publication of texts explaining how to artificially inseminate, and campaigns for gay and lesbian marriage rights led to further intense debate about ‘queer’. Were these efforts to be a 'family' just propping up hetero-patriarchy? The HIV/AIDS epidemic, and moral judgements about this from the Christian right wing, made a culture of casual sex built up during centuries of oppression in gay male communities suddenly life-threateningly problematic.

This historical background offers an epistemological tradition of community discussion about sexuality and gender as context to the current debate about transgender. Hopefully lessons can be learnt from the past too, about how to engage in this debate in ways that don’t exclude and hurt those who are in need of our support – on both sides.

Current debates about transgender.

For ease of reference, let’s take JK Rowling’s tweets, widely criticised as transphobic not only by general commentators, also by actors and actresses made famous by starring in her films like Daniel Radcliffe and Emily Watson.

In an interesting twist, the media host Jonathan Ross initially posted strongly in support of Rowling, then after discussion with his daughter, retracted his support saying he had re-thought his stance.

Meanwhile, Rowling entered a fresh media storm, blogging to explain that her concern about transgender arose from her history in a relationship where she was abused by her male partner. The Sun newspaper was censured (what a surprise) for interviewing her former husband who made controversial headline-grabbing statements about the violent manner in which he had behaved towards Rowling.

This is a core part of argument about transgender rights. Cases are cited where men have posed as transgender, gained admittance to women’s facilities (eg prison) and perpetrated ongoing abuse. Feminists who have long battled against the violence and exploitation in male supremacy which is so routine and mundane that it often gets accepted without question, are horrified at what appears to be tantamount to opening the door and holding it open for psychopathic rapists to gain access to women whose reasons for being institutionalised are often linked to abuse they have previously suffered, but which the State does not appropriately recognise.

Academic writing.

I’m going to put an existential question mark over this argument. Should there not be a distinction between the transgender identity and the psychopathic abuser identity – these two are not essentially the same. In guarding institutional facilities against a manipulative hyper masculinity, should our attention be focussed on transgender people; are manipulative psychopaths actually transgender or posing as transgender to achieve their aims?

- Are transgender politics part of hetero-patriarchy? Or,

- Does transgender politics offer further opportunity to dismantle a system which has long exploited binary sex-gender subject positions?

Below this concern about potential abuse, there is the anxiety about binary gender positions, and in particular the identity which many now call ‘cis-woman’. Having fought long and hard for society to recognise ‘the second sex’ (de Beauvoir, 1949a, 1949b) as a strong and positive identity, it is difficult to see it apparently being thrown under the bus in a movement away from binary sex/gender. Questions still remain about how to ‘be’ woman. Should women aim to break the glass ceiling and achieve as brilliantly in the board room as men? leaving their children and domestic responsibilities to others (quite often women who immigrate to earn money they send home to their own families while bringing up others’ children). Should we aim to change society so that men become more feminine as well as feminist, all of us aiming to balance a good home and family life with career ambitions?

Focus on transgender may distract from these essential questions, leading to men quietly continuing to dominate positions of social power.

Is the transgender cause simply about being recognised and supported with appropriate interventions? which could be argued is a distraction from core feminist aims yet to be achieved. There’s also an argument that it is about changing our society beyond the binary sex/gender divide; that it is about undermining artificial male/female distinctions, and therefore is a feminist cause.

Judith Butler wrote that lesbian women and gay men are highly likely to find transgender troubling. Their sense of identity as much as that of heterosexual people’s, depends on a binary gender: if you are attracted to people of the same sex, then there need to be a different and a same sex for you to be clear about who you find attractive.

A good read to start with, in search of a better sense of how we have arrived at an unpicking of the binary sex/gender which seems so biologically fundamental, is Gayle Rubin’s ‘The Traffic in Women’: a Marxist exegetical examination of the work of Freud and Levi-Strauss – originally written as Rubin’s undergraduate student dissertation. Rubin argues for a ‘political economy of sex’ – an understanding of the binary sex/gender system as underwriting our social systems. “The organization of sex and gender once had functions other than itself – it organized society,” Rubin argues. “Now it mainly organizes and reproduces itself.” (p.65). “We are not only oppressed as women; we are oppressed by having to be women – or men” (p.61). In this classic account, we slowly come to see a system in which sexuality does not arise from there being two biological sexes: heterosexual, you are attracted to the opposite sex; homosexual, you are attracted to the same sex. Rather we come to understand that if sexuality is an ‘economy’, it needs the dynamism created between two different sexes (dynamic energy is generated by both attraction to different and to same sex). It is sexuality – as a crucial driver for society, that gives rise to the need to have two biological sexes. (The term ‘hetero-patriarchy’ acknowledges the key influence of sexuality as well as that of sex/gender.)

This leads us to Butler’s argument that gender is performative, which I haven’t room to go into here (except to say this is not at all the same as saying ‘gender is a performance’ – a persistent misinterpretation of her case which led to Butler having to write a whole second book!).

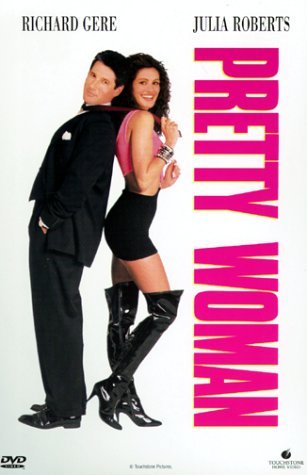

It’s a big ask to throw our sexual economy into the bin, and difficult to imagine erotic feeling without the accoutrements of the binary gender system: stockings and high heels – whether worn by women or men (when there may be the thrill of extra emphasis lent to gender by the cross-dressing); the suited power play of Richard Gere in Pretty Woman; butch/femme or the comfort and pleasure of being with someone of your own sex. It may be hard to imagine sexuality without these.

At the same time, we have seen how these identity positions repeatedly lead to abuse of power: difference should not necessarily mean inequality instead of diversity, but somehow it nearly always seems to go there. Having a more diverse fluid concept of sex/gender might destabilise masculine dominance: it might not be so easy to be top gun in a range of identities, as when there are just two. Beginning to unpick the binary sex/gender economy through genderfluid and non-binary identity may offer us an even braver new world than Miranda imagined when she first saw (young) men in The Tempest.

(In this image from Derek Jarman's The Tempest - from the British Film Institute, Toyah Wilcox looks at the elaborate shoe then she puts it on her head - she doesn't understand how to use this signifier of femininity.)

References:

De Beauvoir, S. (1949a [1979 reprint]). Le deuxième sexe I. Paris : Gallimard.

De Beauvoir, S. (1949b [1979 reprint]). Le deuxième sexe II. Paris : Gallimard.

Rubin, G. (1975) ‘The Traffic in Women: Notes on the “Political Economy” of Sex’ in Rayna R. Reiter (ed.), Toward an Anthropology of Women. Monthly Review Press. pp. 157--210 (1975).

Sedgwick, E.K. (1990). ‘Epistemology of the Closet’. University of California Press.

Comments

New comment

Really interesting. A fascinating subject that I don't currently feel qualified to voice an opinion on but I am reading (or listening rather) to a few audible books on the subject. Nice one Anita.