This

blogpost was written to accompany a short presentation for the Future of

Interdisciplinary Teaching & Learning @ The OU (Online) Conference in

June 2022. It considers whether small group learning might support better

achievement for our students, and might help us close our awarding gap for

Black, Asian and minority ethnic students. It concludes that pro-active inclusive

forum moderation, if resourced through training and workload allocation, could

provide support for all our students and particularly for those from groups who

experience specific barriers in engagement with peer students online.

An

understanding of discrimination and the disadvantages faced by those from

global majority backgrounds was sharply brought into focus in Black Lives

Matter and during the pandemic, when it became clear some communities lacked

access to resources which others hardly think of as a 'privilege'. At the same

time, the pandemic brought online learning front and centre stage as a means of

supporting education.

Drawing

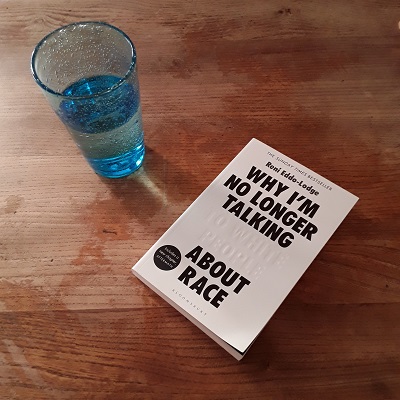

on academic literature about how racism is experienced online (Noxolo, 2022; Noble,

2018), and a small review of literature about issues of race politics in online

learning, this short talk will sketch out some of the issues faced by our

global majority students.

During

the pandemic, it became clearly evident that Black, Asian and minority

ethnic communities and families lack

access to resources which others hardly think of as a ‘privilege’. The murder

of George Floyd and subsequent publicity given to local acts of discrimination

and abuse in the UK also made evident the systemic nature of racism in our

society and institutions. DiAngelo (2018) had written previously about the

insidious ways in which that systemic racism continues to institute a privilege

which global minority people often take for granted, and the ways global

minority people sometimes refuse to acknowledge that the ease with which they

move in society compared to global majority people is other than a norm for

everybody, or a natural state of existence in which they should be allowed to

continue without change. Writers like Noble (2018), Benjamin (2019) and Noxolo

(2022) show how that systemic racism instituted through privilege is also instituted

online. Picower (see my blogpost here) describes the particular struggles for liberal-minded

(school) educators to comprehend systemic racism.

It

has become apparent in Higher Education, that being able to achieve to your

full potential is one of those ‘privileges’ often taken for granted. Here at the Open University, as at

other Higher Education Institutions, we have an ‘awarding gap’ for Black, Asian

and minority ethnic students (Awan, 2020). The size of the gap varies between

different courses of study. It is more substantial for Black students, and

greater for some groups of Asian students than for others. It is clear that we

are not providing all students with the same level of opportunity to gain the

class of degree they deserve. For this reason, we choose to call this the

‘awarding gap’ – putting the responsibility for this failure on our

institution, rather than an ‘achievement gap’ – which suggests that

responsibility rests with individual students (Choak, 2022). We know that

individual Black, and some groups of Asian students, are not getting a ‘level

playing field’ in their studies at the Open University.

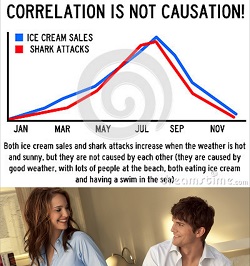

Using

Learning Analytics, Nguyen, Rienties and Richardson (2020) discovered that BME

students at the OU were 19%–79% less likely to complete, pass or achieve an

excellent grade compared to White students. Yet their data also showed that BME

students were studying for 4%–12% more time than White students.

These

findings are echoed in other studies (not very many!) about race and online and

distance learning (based in the United States). There is a shift in these

studies from a qualitative approach (De Montes et al, 2002 and I’m going to

include Triesman, 1992), to a quantitative approach (as can be seen in Nguyen,

Rienties and Richardson’s 2020 study).

Some

studies are about registration rather than an ‘awarding gap’. They explore race

and ethnicity together with other demographic factors (not as ‘intersectional’

identity - Crenshaw, 1989, simply as a set of groups who potentially experience

disadvantage in Higher Education). They find that similar proportions of ethnic

minority students apply to study online as to study on campus (Goodman et al,

2019; Doyle, 2009), although Wladis et al (2015) find that Black and Hispanic

students are significantly under-represented in STEM (Science, Technology,

Engineering and Maths) courses online.

Athens

(2013) offers a more in-depth exploration of ethnicity, achievement and

retention than other quantitative studies. In a similar finding to that of

Nguyen, Rienties and Richardson, she found that young ethnic minority men were

more engaged in their studies than other groups of student, yet got lower

grades and were less likely to continue their studies (retention gap).

Athens’

study defines ‘engagement with studies’ as both engagement with course

materials and interaction with peers. However an earlier study separates these

kinds of engagement. In a study on calculus students, Triesman (1992 and see

discussion in Steele, 2010) found that African-American students spent longer

working with course materials, but did not ask for support not only from

classmates (key in the success of other ethnic groups’ success) – even from

class assistants and lecturers. Their achievement was significantly lower than

both white students (casual chat about studies) and Asian-American students

(regularly working in study groups in the library). This suggests a possible explanation for the

puzzling finding by Nguyen, Rienties and Richardson. BME students at the Open

University may be spending more time studying: but in isolation. Triesman’s

findings suggest that peer group study chat could be a factor in student grades.

(This hypothesis is supported by a large body of literature on small group chat

in online education.)

At

the Open University, the main formal way students are supported to chat about their studies is through online fora. However, there may be good reason

why global majority students would eschew forum discussions.

A small

informal account of forum posting in support of study by Baker et al (2018)

shows that while students would respond at similar levels to posts from other

students with names suggesting diverse ethnic/gender identities, tutors were

twice as likely to respond to a student with a white male sounding name than to

other demographics of student. An earlier qualitative study on forum posting by

De Montes et al (2002) found problematic exchanges between “Anglo”, “Hispanic”

and “Navajo” students. Tutor intervention – in spite of efforts to be neutral

and even-handed, made matters worse. Using a constructivist ontology with

symbolic interactionism and critical theory, the authors identified how “Anglo”

students exert privilege online. They found that when a tutor tried to

intervene in a neutral even-handed way this further instituted white

privilege.

“Computers

are not culturally neutral, they amplify the dominant culture” (Bowers, 2000,

cited in De Montes et al, 2002, p.268). Like Google algorithms (Noble, 2018),

online education is designed and run by (white) humans. These two studies begin

to show how white privilege can be continually re-inscribed into online

learning. This makes group learning opportunities uncomfortable and sometimes

even hostile spaces for global majority students.

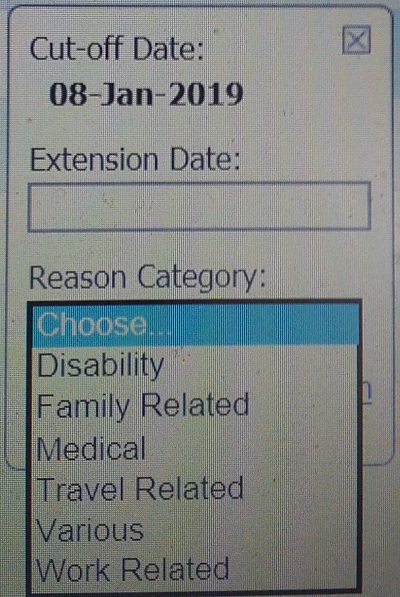

At

the Open University, there are usually two, sometimes three, kinds of fora

provided on each module:

- a forum for a group of 12-25 students run by their own tutor

(Tutor Group Forum),

- a forum for the ‘cluster’ run by tutors who are in a team,

usually teaching across a geographic region (Cluster Forum),

- a ‘Module Forum’, on which the Module Team or Associate

Lecturers employed on separate contracts, will engage with students from across

the module as a whole.

The

amount of time Associate Lecturers spend moderating their own and the Cluster

Forum varies considerably according to personal teaching preferences. (While

some invest time in group forum moderation, others prefer to offer synchronous

one to one tutor-student interaction.) Associate Lecturers can voluntarily sign

up for training in forum moderation. The training, provided by Peer Associate

Lecturer Support and Associate Lecturer Staff and Professional Development

teams, is of a high quality however it is unpaid and busy ALs are unlikely to

prioritise it.

The

human support provided by tutors, with touches of humour and with sympathy or

empathy in difficult situations, is highly valued, especially by under-confident

students who need reassurance to fully engage with their studies. Moderating

fora, and particularly doing so through pro-actively inclusive exercises, is a

technical skill. It can be a time-consuming and emotional labour. Engaged and

open-minded forum discussion could support all of our students to achieve

better. Providing this effectively requires resource investment in training and

workload allocation for our teaching staff.

What can I do?

Central

academic staff: explore whether forum exercises are part of the module

materials. Can these be designed to be more inclusive of global majority

students. Is there scope to allocate teaching hours to bring Associate

Lecturers together for team discussion about how to manage forum moderation,

and perhaps also for workshops on inclusive teaching practice and forum

moderation skills.

Staff

Tutors: discuss with your team of Associate Lecturers whether there are ways to

manage forum moderation so that it is more consistent and more inclusive (if

paid time is available on the module for this discussion work). Many cluster forums

are run on a rota basis, with the moderator changing every couple of weeks to a

different tutor from the cluster: this leads to inconsistent forum support. On

some cluster forums, one tutor or a team of tutors, can use teaching hours to undertake

the forum moderation, with other tutors choosing to do more teaching via

cluster tutorials. Consider which approach would best support students in your

cluster. Can teaching time also be utilised to allow the tutor moderators to

undertake training.

Associate

Lecturers: inclusive education teaching is often additional work which should be part of

your paid hours. (If some of us undertake additional work voluntarily, while others

stick to core contractual teaching tasks, it will not be possible to support a

fully inclusive environment at the university.) If you have got scope in your

paid teaching duties to develop inclusive teaching as part of forum moderation,

you might like to consider:

- Putting up a thread at key dates (see blogpost);

- Highlighting material in the module which allows students to have

a discussion about equalities;

- Putting up material about topical events or other items about

equalities, which are also of relevant interest for the students on that

module, for moderated discussion.

References:

Athens, W. (2018)

‘Perceptions of the persistent: Engagement and learning community in

underrepresented populations’, Online Learning Journal, 22(2), pp.

27–58.

Awan, R. (2020). ‘The

awarding gap at The Open University’ on OpenLearn. Available at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/education-development/the-awarding-gap-the-open-university (accessed 17/06/2022).

Baker, R., Dee, T.S., Evans,

B. and John, J. (2018) ‘Race and gender biases appear in online education’.

Available at:

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/04/27/race-and-gender-biases-appear-in-online-education/

(Accessed: 11/072020).

Benjamin, R. (2019) Race

After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge:

Polity Press.

Choak, C. (2022). ‘Decolonisation

and Higher Education: Closing the Degree Awarding Gap’ on OpenLearn. Available

at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/education-development/decolonisation-and-higher-education-closing-the-degree-awarding-gap (accessed 17/06/2022).

Crenshaw, K. (1989)

‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of

antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’.

University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139, 139–167.’, University of Chicago Legal

Forum.

De Montes, L. E. S., Oran,

S. M. and Willis, E. M. (2002) ‘Power, language, and identity: Voices from an

online course’, Computers and Composition, 19(3), pp. 251–271.

DiAngelo, R. (2018) White

Fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Allen

Lane.

Doyle, W. R. (2009) ‘Online

Education: The Revolution That Wasn’t’, Change: The Magazine of Higher

Learning. Informa UK Limited, 41(3), pp. 56–58.

Goodman, J., Melkers, J. and

Pallais, A. (2019) ‘Can Online Delivery Increase Access to Education?’, Journal

of Labor Economics. University of Chicago Press, 37(1), pp. 1–34.

Nguyen, Q., Rienties, B. and

Richardson, J. T. E. (2020) ‘Learning analytics to uncover inequality in

behavioural engagement and academic attainment in a distance learning setting’,

Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), pp. 594–606. doi:

10.1080/02602938.2019.1679088.

Noble, S. U. (2018) Algorithms

of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York

University Press.

Noxolo, P. (2022). ‘Dreading

the Map’. Talk given at the Royal Geographical Society, on 28 Apr 2021.

Details: https://www.rgs.org/geography/news/dreading-the-map/ (Accessed 17/06/2022).

Steele, C. (2010) Whistling

Vivaldi: how stereotypes affect us and what we can do. New York: W.W.

Norton.

Treisman, U. (1992)

‘Studying Students Studying Calculus: A Look at the Lives of Minority

Mathematics Students in College’. The College Mathematics Journal Vol.

23, No. 5 (Nov., 1992), pp. 362-372.

Wladis, C., Hachey, A. C.

and Conway, K. (2015) ‘Which STEM majors enroll in online courses, and why

should we care? The impact of ethnicity, gender, and non-traditional student

characteristics’, Computers and Education. Elsevier Ltd, 87, pp.

285–308.

I did laugh when I saw that the garden which won was the one that I admitted was my personal favourite - which I had set aside in the voting in order to support my political convictions. However this choice by so many other people made me think.

I did laugh when I saw that the garden which won was the one that I admitted was my personal favourite - which I had set aside in the voting in order to support my political convictions. However this choice by so many other people made me think.  I have put aside a square of garden for loose wildflower planting, but in the rest of my garden I use arches and a trellised arbour seat to give a sense of structure.

I have put aside a square of garden for loose wildflower planting, but in the rest of my garden I use arches and a trellised arbour seat to give a sense of structure.

The Perennial Garden 'With Love' by Richard Miers (@richardmiers on Instagram) is a return to formal garden design, with playful touches. Its model is the arty witty

The Perennial Garden 'With Love' by Richard Miers (@richardmiers on Instagram) is a return to formal garden design, with playful touches. Its model is the arty witty  This year, the Hands Off Mangrove garden (designed by Tayshan Hayden-Smith, @ths62 on Instagram, and Danny Clarke, @theblackgardener on Instagram) brings racial justice sharply to the forefront, in a showcase event which has been a traditional preserve for those at the highest levels of society. Even the Queen comes every year to RHS Chelsea. I would like to be able to say, this shows that society is shifting towards a time when we might not see a

This year, the Hands Off Mangrove garden (designed by Tayshan Hayden-Smith, @ths62 on Instagram, and Danny Clarke, @theblackgardener on Instagram) brings racial justice sharply to the forefront, in a showcase event which has been a traditional preserve for those at the highest levels of society. Even the Queen comes every year to RHS Chelsea. I would like to be able to say, this shows that society is shifting towards a time when we might not see a  Personally I did like seeing a return to the formal design represented in The Perennial Garden 'With Love', its explicit reference to Victoriana and the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. I grew up visiting gardens with my mum, and inherited her books about Italianate gardens where roses gracefully soften the lines of stone ruins. Like many immigrants, mum carefully studied and reproduced English style in her life, particularly in creating her elegant garden. I favour a loose informal planting style myself, however seeing Richard Miers' garden made me realise how I prevent this becoming just a plant-y mess by using a framework of formal structures.

Personally I did like seeing a return to the formal design represented in The Perennial Garden 'With Love', its explicit reference to Victoriana and the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. I grew up visiting gardens with my mum, and inherited her books about Italianate gardens where roses gracefully soften the lines of stone ruins. Like many immigrants, mum carefully studied and reproduced English style in her life, particularly in creating her elegant garden. I favour a loose informal planting style myself, however seeing Richard Miers' garden made me realise how I prevent this becoming just a plant-y mess by using a framework of formal structures.

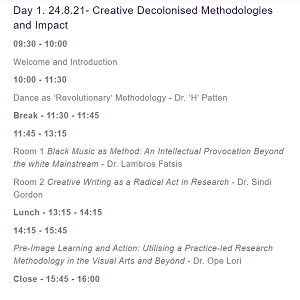

On Instagram recently, an event caught my eye: epitomising some of the differences I have begun to think through about ways that global majority scholars go about our research. Even the fact that the event was being advertised on Instagram, rather than just via a scholarly email list, was different. The programme is not aimed at peers with influence in the editing boards of prestigious journals, but at PhD and doctoral researchers: at reaching out to upcoming scholars. It offers different approaches to research: dance, music and creative writing as method; finding your 'voice', community transformation in research (Ebony Initiative, 2021).

On Instagram recently, an event caught my eye: epitomising some of the differences I have begun to think through about ways that global majority scholars go about our research. Even the fact that the event was being advertised on Instagram, rather than just via a scholarly email list, was different. The programme is not aimed at peers with influence in the editing boards of prestigious journals, but at PhD and doctoral researchers: at reaching out to upcoming scholars. It offers different approaches to research: dance, music and creative writing as method; finding your 'voice', community transformation in research (Ebony Initiative, 2021).  During my own research career, initially as a PhD student, now as an academic educator, I have been conscious of struggling to fit my ideas into mainstream academic writing. Here I reflect on some of the different ways in which those from the 'global majority' might slip through 'global minority'/'global North' (Europe, USA, Australasia) ways of measuring and capturing academic thought. This makes us look as if we are not achieving well in the ivory tower of a white higher education system.

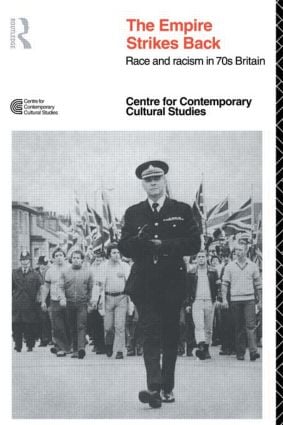

During my own research career, initially as a PhD student, now as an academic educator, I have been conscious of struggling to fit my ideas into mainstream academic writing. Here I reflect on some of the different ways in which those from the 'global majority' might slip through 'global minority'/'global North' (Europe, USA, Australasia) ways of measuring and capturing academic thought. This makes us look as if we are not achieving well in the ivory tower of a white higher education system.  In 1982, a collection of essays was published by a group of young scholars at Birmingham University. Unlike other scholarly collections, it didn't bear the names of individuals who had edited it. It has to be referenced as (Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 1982). Inside, the scholars wrote of the way in which all had influenced each piece of writing, of how they had supported each other and thought through ideas being offered together. They didn't want to claim individual acknowledgement for the collection, they wanted to acknowledge their collaborative approach to writing.

In 1982, a collection of essays was published by a group of young scholars at Birmingham University. Unlike other scholarly collections, it didn't bear the names of individuals who had edited it. It has to be referenced as (Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 1982). Inside, the scholars wrote of the way in which all had influenced each piece of writing, of how they had supported each other and thought through ideas being offered together. They didn't want to claim individual acknowledgement for the collection, they wanted to acknowledge their collaborative approach to writing.  In their 2020 review of innovations in pedagogy, Kukulska-Hulme

et al suggested we take a post-humanist approach in education. Here I argue

instead for a ‘small is beautiful’ (Schumacher, 1973) humanist approach,

particularly for distance and online learning institutions like the Open

University.

In their 2020 review of innovations in pedagogy, Kukulska-Hulme

et al suggested we take a post-humanist approach in education. Here I argue

instead for a ‘small is beautiful’ (Schumacher, 1973) humanist approach,

particularly for distance and online learning institutions like the Open

University.

The extreme variability of broadband provision across the UK

is such a known issue that it formed part of the Labour Party’s last election manifesto

(2019). A tutor for the Open University in South Wales, I am constantly minimising

the data used in my online teaching, to ensure access for students in remote

rural and coastal locations with poor broadband and mobile signal provision. I sometimes

have to go back over tutorials in one to one sessions with students who dropped

out of the tutorial. When teaching colleagues have asked about problems

dropping out of their own tutorial because of issues with their broadband

provision, we have been advised to tell our children not to livestream while we

teach. This is not a sympathetic humanist or feminist solution. (I wish those

people would try teaching with a small child loudly demanding chocolate down

the microphone because they aren’t able to watch what they wanted to for the

hour of the tutorial.)

The extreme variability of broadband provision across the UK

is such a known issue that it formed part of the Labour Party’s last election manifesto

(2019). A tutor for the Open University in South Wales, I am constantly minimising

the data used in my online teaching, to ensure access for students in remote

rural and coastal locations with poor broadband and mobile signal provision. I sometimes

have to go back over tutorials in one to one sessions with students who dropped

out of the tutorial. When teaching colleagues have asked about problems

dropping out of their own tutorial because of issues with their broadband

provision, we have been advised to tell our children not to livestream while we

teach. This is not a sympathetic humanist or feminist solution. (I wish those

people would try teaching with a small child loudly demanding chocolate down

the microphone because they aren’t able to watch what they wanted to for the

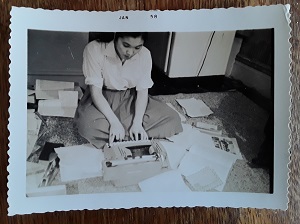

hour of the tutorial.)  Kukulska-Hulme et al (2020) provide examples of education

projects in the global South which successfully engaged learners with offline

learning, connecting them in ‘communities of practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991).

These could offer value not only to students with poor broadband; also to Students

In Secure Environments (prison). (Illustration on the right is from the report.)

Kukulska-Hulme et al (2020) provide examples of education

projects in the global South which successfully engaged learners with offline

learning, connecting them in ‘communities of practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991).

These could offer value not only to students with poor broadband; also to Students

In Secure Environments (prison). (Illustration on the right is from the report.)

(By British Government - This is photograph Q 71073 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums., Public Domain,

(By British Government - This is photograph Q 71073 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums., Public Domain,  (Photo from frontispiece of Owen's collection of poerms

(Photo from frontispiece of Owen's collection of poerms  (A Cornfield by Moonlight with the Evening Star, by Samuel Palmer - image available copyright free from Wikipedia.

(A Cornfield by Moonlight with the Evening Star, by Samuel Palmer - image available copyright free from Wikipedia.

Victoria Drummond OBE - Day 2. Check out the link to see the rest.

Victoria Drummond OBE - Day 2. Check out the link to see the rest.