The idea of gathering a substantial part of one’s life experience fascinates me, as it has often inspired others

Thursday 31 January 2013 at 05:03

Visible to anyone in the world

Edited by Jonathan Vernon, Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 09:42

Fig. 1. Hands by Escher.

The danger is for it to become one’s modus operandi, that the act of gathering is what you become. I recall many decades ago, possibly when I started to keep a diary when I was 13, a documentary - that can no doubt now be found on the Internet - on a number of diarists. There were not the well-known authors or celebrity politicians, but the obscure keeper of the heart beat, those who would toil for two hours a day writing about what they had done, which was to edit what they’d written about the day before … if this starts to look like a drawing by Escher then perhaps this illustrates how life-logging could get out of hand, that it turns you inside out, that it causes implosion rather than explosion. It may harm, as well as do good. We are too complex for this to be a panacea or a solution for everybody. A myriad of book, TV and Film expressions of memory, its total recall, false recall, falsehoods and precisions abound. I think of the Leeloo in The Fifth Element learning about Human Kind flicking through TV Channels.

Fig. 2. Leeloo learns from TV what the human race is doing to itself

Always the shortcut for an alien to get into our collective heads and history. Daryl Hannah does it in Splash too. Digitisation of our existence, in part or total, implies that such a record can be stored (it can) and retrieved in an objective and viable way (doubtful). Bell (2009) offers his own recollections, sci-fi shorts and novels, films too that of course push the extremes of outcomes for the purposes of storytelling rather than seeking more mundane truth about what digitization of our life story may do for us.

Fig. 3. Swim Longer, Faster

There are valid and valuable alternatives - we do it anyway when we make a gallery of family photos - that is the selective archiving of digital memory, the choices over what to store, where to put it, how to share then exploit this data. I’m not personally interested in the vital signs of Gordon Bell’s heart-attack prone body, but were I a young athlete, a competitive swimmer, such a record during training and out of the pool is of value both to me and my coach. I am interested in Gordon Bell’s ideas - the value added, not a pictoral record of the 12-20 events that can be marked during a typical waking day, images grabbed as a digital camera hung around his neck snaps ever 20-30 seconds, or more so, if it senses ‘change’ - gets up, moves to another room, talks to someone, browses the web … and I assume defecates, eats a meal and lets his eyes linger on … whatever takes his human fancy.

How do we record what the mind’s eye sees?

How do we capture ideas and thoughts? How do we even edit from a digital grab in front of our eyes and pick out what the mind is concentrating on? A simple click of a digital camera doesn’t do this, indeed it does the opposite - it obscure the moment through failing to pick out what matters. Add sound and you add noise that the mind, sensibly filters out. So a digital record isn’t even what is being remembered. I hesitate as I write - I here two clocks. No, the kitchen clock and the clicking of the transformer powering the laptop. And the wind. And the distant rumble of the fridge. This is why I get up at 4.00am. Fewer distractions. I’ve been a sound engineer and directed short films. I understand how and why we have to filter out extraneous noises to control what we understand the mind of the protagonist is registering. If the life-logger is in a trance, hypnotized, day dreaming or simply distracted the record from the device they are wearing is worse than an irrelevance, it is actually a false cue, a false record.

Fig. 4. Part of the brain and the tiniest essence of what is needed to form a memory

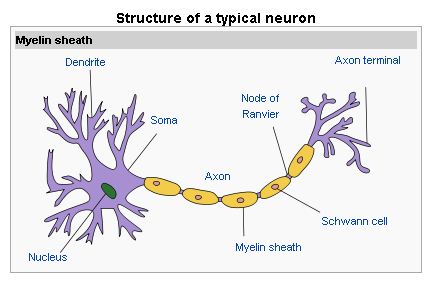

Mind is the product of actions within a biological entity. To capture a memory you’d have to capture an electro-chemical instance

across hundreds of millions of synapses.

Fig. 5. Diving of Beadnell Harbour, 1949. My later mother in her teens.

An automatically harvested digital record must often camouflage what might have made the moment a memory. I smell old fish heads and I see the harbour at Beadnell where as a child fisherman brought in a handful of boats every early morning. What if I smell old fish as I take rubbish to recycle? Or by a bin down the road from a fish and chip shop. What do my eyes see, and what does my mind see?

I love the messiness of the human brain - did evolution see this coming?

In ‘Delete’ Mayer-Schönberger (2009. p. 1) suggests that forgetting, until recently was the norm, whereas today, courtesy of our digital existences, forgetting has become the exception. I think we still forget - we don’t try to remember phone numbers and addresses as we think we have them in our phone - until we wipe or lose the thing. In the past we’d write them down, even make the effort to remember the things. It is this need to ‘make an effort’ to construct a memory that I fear could be discombobulated. I’m disappointed though that Mayer-Schönberger stumbles for the false-conception ‘digital natives’ - this is the mistaken impression that there exists a generation that is more predisposed and able than any other when it comes to all things digital. Kids aren’t the only ones with times on their hands, or a passion for the new, or even the budget and will to be online. The empirical evidence shows that the concept of a digital native is unsound - there aren’t any. (Jones et al, 2010., Kennedy et al, 2009., Bennet and Maton, 2010., Ituma, 2011) The internet and digital possibilities have not created the perfect memory. (Mayer-Schönberger 2009. p. 3)

To start with how do we define ‘memory’ ?

A digital record is an artefact, it isn’t what is remembered at all. Indeed, the very nature of memory is that it is different every time you recall a fact or an event. It becomes nuanced, and coloured. It cannot help itself.

Fig. 6. Ink drops as ideas in a digital ocean

A memory like drops of ink in a pond touches different molecules every time you drip, drip, drip. When I hear a family story of what I did as a child, then see the film footage I create a false memory - I think I remember that I see, but the perspective might be from my adult father holding a camera, or my mother retelling the story through ‘rose tinted glasses’.

Fig. 7. Not the first attempt at a diary, that was when I was 11 ½ .

I kept a diary from March 1973 to 1992 or so. I learnt to write enough, a few bullet points in a five year diary in the first years - enough to recall other elements of that day. I don’t need the whole day. I could keep a record of what I read as I read so little - just text books and the odd novel. How might my mind treat my revisting any of these texts? How well and quickly would it be recalled? Can this be measured? Do I want it cluttering the front of my brain?

The idea of gathering a substantial part of one’s life experience fascinates me, as it has often inspired others

Fig. 1. Hands by Escher.

The danger is for it to become one’s modus operandi, that the act of gathering is what you become. I recall many decades ago, possibly when I started to keep a diary when I was 13, a documentary - that can no doubt now be found on the Internet - on a number of diarists. There were not the well-known authors or celebrity politicians, but the obscure keeper of the heart beat, those who would toil for two hours a day writing about what they had done, which was to edit what they’d written about the day before … if this starts to look like a drawing by Escher then perhaps this illustrates how life-logging could get out of hand, that it turns you inside out, that it causes implosion rather than explosion. It may harm, as well as do good. We are too complex for this to be a panacea or a solution for everybody. A myriad of book, TV and Film expressions of memory, its total recall, false recall, falsehoods and precisions abound. I think of the Leeloo in The Fifth Element learning about Human Kind flicking through TV Channels.

Fig. 2. Leeloo learns from TV what the human race is doing to itself

Always the shortcut for an alien to get into our collective heads and history. Daryl Hannah does it in Splash too. Digitisation of our existence, in part or total, implies that such a record can be stored (it can) and retrieved in an objective and viable way (doubtful). Bell (2009) offers his own recollections, sci-fi shorts and novels, films too that of course push the extremes of outcomes for the purposes of storytelling rather than seeking more mundane truth about what digitization of our life story may do for us.

Fig. 3. Swim Longer, Faster

There are valid and valuable alternatives - we do it anyway when we make a gallery of family photos - that is the selective archiving of digital memory, the choices over what to store, where to put it, how to share then exploit this data. I’m not personally interested in the vital signs of Gordon Bell’s heart-attack prone body, but were I a young athlete, a competitive swimmer, such a record during training and out of the pool is of value both to me and my coach. I am interested in Gordon Bell’s ideas - the value added, not a pictoral record of the 12-20 events that can be marked during a typical waking day, images grabbed as a digital camera hung around his neck snaps ever 20-30 seconds, or more so, if it senses ‘change’ - gets up, moves to another room, talks to someone, browses the web … and I assume defecates, eats a meal and lets his eyes linger on … whatever takes his human fancy.

How do we record what the mind’s eye sees?

How do we capture ideas and thoughts? How do we even edit from a digital grab in front of our eyes and pick out what the mind is concentrating on? A simple click of a digital camera doesn’t do this, indeed it does the opposite - it obscure the moment through failing to pick out what matters. Add sound and you add noise that the mind, sensibly filters out. So a digital record isn’t even what is being remembered. I hesitate as I write - I here two clocks. No, the kitchen clock and the clicking of the transformer powering the laptop. And the wind. And the distant rumble of the fridge. This is why I get up at 4.00am. Fewer distractions. I’ve been a sound engineer and directed short films. I understand how and why we have to filter out extraneous noises to control what we understand the mind of the protagonist is registering. If the life-logger is in a trance, hypnotized, day dreaming or simply distracted the record from the device they are wearing is worse than an irrelevance, it is actually a false cue, a false record.

Fig. 4. Part of the brain and the tiniest essence of what is needed to form a memory

Mind is the product of actions within a biological entity. To capture a memory you’d have to capture an electro-chemical instance

across hundreds of millions of synapses.

Fig. 5. Diving of Beadnell Harbour, 1949. My later mother in her teens.

An automatically harvested digital record must often camouflage what might have made the moment a memory. I smell old fish heads and I see the harbour at Beadnell where as a child fisherman brought in a handful of boats every early morning. What if I smell old fish as I take rubbish to recycle? Or by a bin down the road from a fish and chip shop. What do my eyes see, and what does my mind see?

I love the messiness of the human brain - did evolution see this coming?

In ‘Delete’ Mayer-Schönberger (2009. p. 1) suggests that forgetting, until recently was the norm, whereas today, courtesy of our digital existences, forgetting has become the exception. I think we still forget - we don’t try to remember phone numbers and addresses as we think we have them in our phone - until we wipe or lose the thing. In the past we’d write them down, even make the effort to remember the things. It is this need to ‘make an effort’ to construct a memory that I fear could be discombobulated. I’m disappointed though that Mayer-Schönberger stumbles for the false-conception ‘digital natives’ - this is the mistaken impression that there exists a generation that is more predisposed and able than any other when it comes to all things digital. Kids aren’t the only ones with times on their hands, or a passion for the new, or even the budget and will to be online. The empirical evidence shows that the concept of a digital native is unsound - there aren’t any. (Jones et al, 2010., Kennedy et al, 2009., Bennet and Maton, 2010., Ituma, 2011) The internet and digital possibilities have not created the perfect memory. (Mayer-Schönberger 2009. p. 3)

To start with how do we define ‘memory’ ?

A digital record is an artefact, it isn’t what is remembered at all. Indeed, the very nature of memory is that it is different every time you recall a fact or an event. It becomes nuanced, and coloured. It cannot help itself.

Fig. 6. Ink drops as ideas in a digital ocean

A memory like drops of ink in a pond touches different molecules every time you drip, drip, drip. When I hear a family story of what I did as a child, then see the film footage I create a false memory - I think I remember that I see, but the perspective might be from my adult father holding a camera, or my mother retelling the story through ‘rose tinted glasses’.

Fig. 7. Not the first attempt at a diary, that was when I was 11 ½ .

I kept a diary from March 1973 to 1992 or so. I learnt to write enough, a few bullet points in a five year diary in the first years - enough to recall other elements of that day. I don’t need the whole day. I could keep a record of what I read as I read so little - just text books and the odd novel. How might my mind treat my revisting any of these texts? How well and quickly would it be recalled? Can this be measured? Do I want it cluttering the front of my brain?