Let’s turn that news off and get into something positive. Let’s rewrite the story. No this isn’t a university essay; there are no bad answers or negative feedback. We all have the story inside us but we have never put pen to paper and told it. Here is the theme:

If You Were to Rewrite the Story of Life on Planet Earth, What Would You Create?

Go on now, get your notebook and start your story. No writer's block, we all have the story in our head and hearts.

No cheating now. Don’t look at my story until you have written yours.

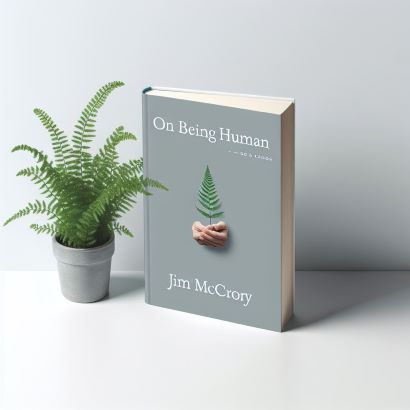

Image kindly provided by https://unsplash.com/@goldenplover31

My Story

I remember walking through a small village in Italy one day when a family spotted us passing and called out from their terrace, “Ciao, benvenuti!”—or words to that effect—welcoming us to join them. I found it deeply moving.

That would be my first quality in the story I’d want to tell: a human family that is welcoming and compassionate. Where empathy isn’t a soft virtue but a foundational principle—extended to every person granted entry into my imagined world. There would be no families dying with their children as they attempted to negociant vast oceans to escape poverty. The migrant would feel safe and wanted and loved.

I’ve visited some stunning places in my life, but when I look at how people treat my own town, I feel ashamed. I see young people throw takeaway cartons and drinks cups out their car windows. I see illegal dumping—mattresses, building waste—left in rural spots like they’re rubbish tips. I read about fishermen scouring the surface of the ocean and reducing it to a desert wasteland. And then there’s the question of how future generations will deal with nuclear waste buried in mountains and other so-called "safe" places.

In my story, the human family would finally learn responsible stewardship of the earth. Humanity would live with nature, not above it. Forests wouldn’t be razed—they’d be revered. Oceans wouldn’t be dumped in—they’d be dwelt beside, with awe. Animals would be treated with respect, and the earth would resemble those beautiful places I’ve been fortunate enough to walk through.

Many people are hurting. There are bullies in schools and workplaces. Young people spiralling into depression because there are no opportunities. Exploitation in work. Child abuse. Economic hardship. Some are relying on foodbanks just to get by. I know that feeling. I remember growing up in Govan, Glasgow, when money would run out on a Wednesday night, and there’d be nothing in the larder for Thursday and Friday until my father got paid.

So in my story, work would mean something. It would nurture instead of consume. Imagine a society where work is aligned with purpose, creativity, and contribution—not just survival. A world where people farm, build, teach, and heal with joy. A place where tribalism gives way to kinship. Where children play safely in a Gyo Fujikawa-type world: treehouses, lakes, talking plants, and wise animals who speak.

But there’s something else my world would need—something crucial.

Redemption built into the system.

The right to begin again.To rewrite your story as part of the bigger one.

A grace-filled society that offers second chances. I’ve spoken to street people whose stories are heartbreakingly raw: thrown out because they were autistic, given drugs and alcohol as children by their own parents, marriage breakdowns that led to financial ruin, and just plain lack of wisdom. We all long for the chance to wipe the slate clean—to keep the good memories and delete the bad ones, to have the right to rewrite the story.

And what about loss? The loss of a child. The loss of more than one child. The loss of a partner. Watching a loved one slowly taken by cancer or another cruel illness. What if we could wipe those slates clean too—and bring them back? Restore everything to perfection. Wouldn’t that be a beautiful story?

That’s why I must include it.

I’ll stop there.

Did you like my story?

I wonder—did you tick some of the same boxes as me?

Go on, tell me your story, even if it’s just a rough outline.

Post it in the comments below. You can do it anonymously email me confidentially

at

planetmilenia@gmail.com

We will return to this later this week.