Over the past two weeks, I experienced the most severe respiratory illness of my adult life.

What started as a cold quickly went to my chest. I lost several days and nights to relentless coughing fits, barely sleeping and feeling completely drained. When I began blowing my nose, the tissues were first speckled with blood, then suddenly drenched in blood mixed with phlegm, which was alarming and heightened the sense that something wasn’t right.

I’m asthmatic but usually well controlled, and initially this presented as a heavy viral cough. As symptoms escalated, I deliberately used AI as a structured thinking and communication aid — not for diagnosis, but to organise information and make sense of what was happening.

I shared accurate background information (age, asthma history, usual peak flow, medications), daily symptoms, objective measurements (peak flow trends, temperature, heart rate), and responses to treatment. The AI helped me interpret patterns, distinguish between infection and airway inflammation, and identify when recovery had plateaued rather than progressed.

Crucially, it helped me translate this information into clear, clinically relevant language suitable for NHS triage systems — concise summaries that highlighted objective deterioration, functional impact, and the reasons for intervention. This avoided both minimisation and alarmism. As a result, I was booked for a face-to-face GP appointment rather than dismissed as “just a cough.”

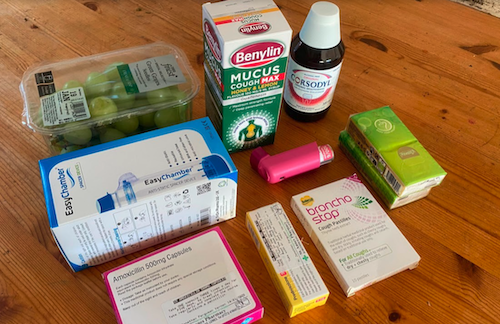

At the surgery, the clinical outcome aligned closely with the structured reasoning developed beforehand: the GP identified a viral-triggered asthma exacerbation and initiated appropriate management—oral steroids, standby antibiotics, improved inhaler delivery via a spacer, and a planned asthma review once recovery was complete. I now have a clear treatment plan, objective markers to monitor recovery, and guidance on pacing my return to work.

The value of AI here was not replacing medical judgment or bypassing clinicians. It acted as a cognitive scaffold, helping me organise complex, evolving information, maintain perspective during illness, and communicate efficiently within a strained healthcare system. It supported timely escalation rather than self-diagnosis. In short, AI functioned as a tool for improved patient advocacy and clearer clinical dialogue, enabling the NHS to do what it does best—assess, treat, and plan care—with better information and less friction.

Over a decade ago, drawing on my MAODE from the Open University, I proposed a PhD research project exploring how online learning could improve compliance with prescribed medication and health monitoring. The aim was to conduct a three-year study using measurable behavioural change and asthma statistics to assess whether structured online learning improved adherence and outcomes. A decade on, the case for this approach remains strong, arguably stronger.

I still have that PhD research proposal. I should give it a second airing. The University of Southampton rejected me at the time.

Quiz time: Study the attached image. For those who were ever tucked into bed with a hot water bottle, off school with a cold, what else did you expect in addition to grapes?!