As part of my applied linguistics learning, a context which I very recently experienced and observed, in which I think ethnography might be appropriate is medical treatment during COVID. Within that context, I would be interested in focusing on intercultural communication / intracultural diversity in healthcare. Ethnography would be appropriate in the context chosen because of the clear differences in clinical outcomes for particular ethnic groups in the NHS - ethnography as a social science. I will not go into the hundreds of studies on this. I will focus on COVID:

'...the failure to record the race and ethnicity of Covid-19 deaths, and the disproportionate mortality impact...on Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities, speaks to a systemic failure to account for the ...the social construction of race, the lived experience of racism, and its biological presentation as 'poor health' amongst the discriminated-against.'

(Fofana, 2020, p.1)

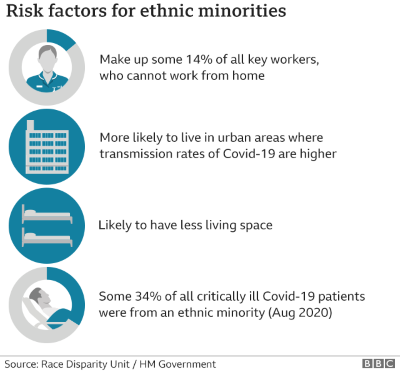

It is also important to note that others have placed other factors above race as a cause of inequalities (see Mundasad, 2020).

The care I received was better than good, I’d say excellent. I’d gone into the hospital partly as a precaution against COVID. I was given a test as a precaution. My test was negative (btw). I went home stable and very thankful to the doctors, nurses, paramedics who showed such sensitive and devoted care. But from the beginning, I felt that need to keep throwing out signals to them that I thought would creae a kind of 'one of us' effect and lessen the effect of society's blind spot in its care of BAME (hate that term) - especially African-Caribbean.

Green and Bloome’s categories (cited in Street, 2010 p.204), an ethnographic perspective would be most relevant - there has already been a lot proven and written on disparities in social services provision along race and ethnic lines. This would focus on staff-staff and staff-patient interactions that impact one control and one study group of patients - an ethnographic account, using theories, practices and ethnographic tools derived from anthropology and sociology (Green and Bloome, 2004). My paradigmatic perspective would be critical and should have a commitment to action and reform as it addressed long entrenched issues, that could end up providing a telling case study. The shortfall in care for BAME I believe is real, bourne out by consistent observations, no matter how heroic our NHS staff is in general, a problem exists. Green and Bloome provide some ethnographic questions (2004, p.2), they say as a way of ‘making visible what those who engage in ethnography mean by this term’ (2004, p.3) and I think these also provide a basis for criticality and reflection on the situatedness of ethnology when looking into the generalizability of the research ‘findings’.

I think that both black and white participant-observers who are sociolinguists would be great assets in this type of research – they can see first-hand how verbal communication is dealt with in interactions with someone of their ‘demographic’. The importance of NVB is crucial here too.

Did my ethnicity become an unwelcome part of my encounter and a possible sign of the above-mentioned cracks in society?

It did, but perhaps not from a negative care perspective. Race was brought up in a context that only presented a danger of misinterpretation in itself but seemed to point to issues below the surface. It was, once again, about how black men are seen as threatening or frightening and our 'physicality' often comes up. It's astonishing how frequently, once people relax with you it comes up. It's a linguistic ritual that accounts for people's knowledge of how BAME people are presented by society. In this case, it seemed to be a deliberate counter to stereotypes I think the staff member may have encountered herself at work. A lot of questions were left unanswered as I was not conducting research at the time.

'cultural differences may also contribute to stereotyping behaviour and biased or prejudicial attitudes toward patients and healthcare providers. At the same time, cultural beliefs and approaches to healthcare are deeply ingrained and most often not overtly communicated'. (Kirschbaum, 2017 p.1 ):

References

Fofana, M.O., 2020. Decolonising global health in the time of COVID-19. Global public health, pp.1-12.

Green, J. and Bloome, D. (2004) ‘Ethnography and ethnographers of and in education: A situated perspective’ Handbook of research on teaching literacy through the communicative and visual arts, pp.181-202.

Kirschbaum, K.A., 2017. Intercultural communication in healthcare. The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication, pp.1-13.

Street, B. (2010) ‘Adopting an ethnographic perspective in research and pedagogy’ in Coffin, C., Lillis, T. and O’Halloran, K. (eds) Applied Linguistic Methods: A reader, Abingdon, Routledge, pp. 201–15.