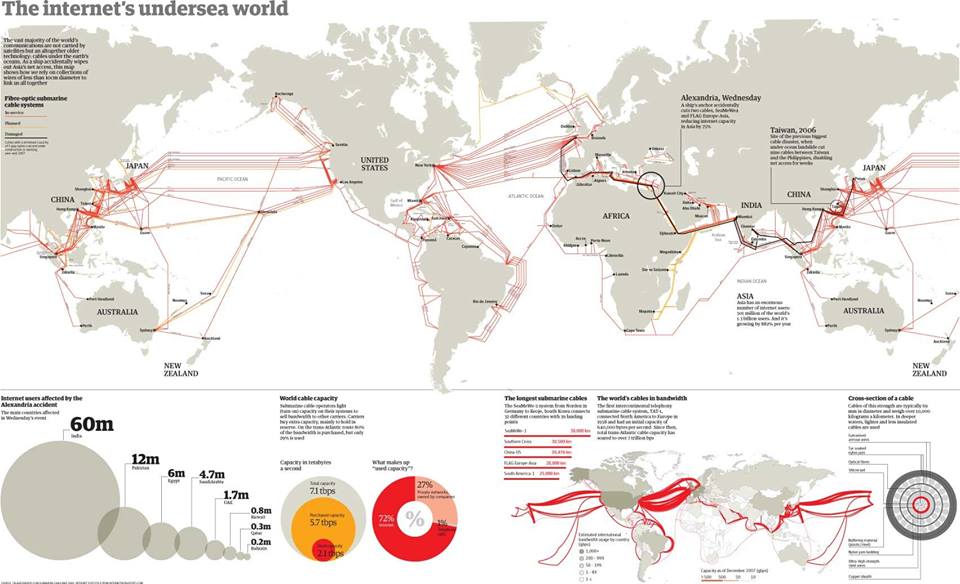

One of the activities I plan to write about in my TMA is the Global Digital Divide. When doing this activity a few weeks ago I looked at the region (ha!) of Africa (a pretty big region!) and speculated that the provision of OERs by western universities would be unlikely to be helpful to most people in Africa as internet connectivity was both rare, poor and expensive. I looked up infographics to show how the undersea cabling simply didn't reach Africa as strongly as it reached North America and Europe.

https://www.submarinecablemap.com/#/

I assumed that the vastness, and relatively emptiness, of the African continent meant that stretching the infrastructure from the coast inland simply hadn't been done and therefore, the videos, quizzes, resources and lectures being provided 'for free' would not actually contribute to the improvement of the learning environment for Africans but rather sit there uselessly - an unusable but expensive white elephant.

However - this was based on the information linked to by H800 - mostly at least 5 years old.

I've now done some much more up to date research (aided by the hive mind that is Facebook and specifically three computer-y friends who exploded with geekiness upon being asked for advice and information!) and see that the global digital divide is narrowing - pretty much before our eyes in a visible way.

This website is full of very up to date information about the whole world and if, how and why it connects to the internet. 153 pages of fascinating data. Yet not one which expressly refers to learning or education. Lots about social media, banking, commerce... but no learning.

I also was linked to this initiative by Facebook which also fails to explicitly refer to education and learning except for two video diaries of learners - one school boy and one adult learner. It addresses connectivity and some of the technical efforts they are making to address the shrinking inequality.

Other projects were linked to which had the aim of both strengthening the internet connection in Africa, and utilizing it for the common good in various ways - though education was, once more, notable in its absence.

So it's back to the drawing board! I think that 10 years ago my planned plea for OERs to be made in text form, avoiding bandwidth munching pictures and videos, would have been right on the money! However - now I think I will have to rethink. Maybe the same problems which always faces schools in Africa will be the key - simply having buildings, teachers, uniforms and equipment will continue to be the challenge. The equipment may be more technological, and the teachers may need more training and the buildings may need internet connectivity.... yeah - there's still 1000 words in that!