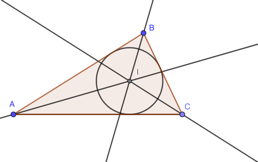

More than 2,000 years ago Euclid proved that in any triangle the three lines bisecting the angles of a triangle meet at a point which is the centre of the circle that touches the triangle's sides.

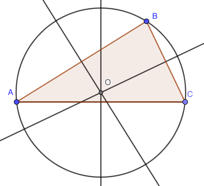

He further proved that the three lines that bisect the triangle's sides at right angles is the centre of a circle passing through the triangles three corners.

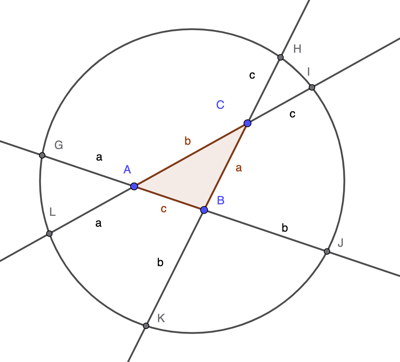

These circles, called the incircle (centre incentre) and circumcircle (centre circumcentre) still studied in schools today, for example here is quite a nice animation showing the construction of the circumcircle, from a GCSE revision site.

And if you are interested in Euclid's original proofs here you can see the relevant pages from the oldest know complete copy of Euclid's Elements, with a transcription into a readable form and an English translation. You want Book IV, Elem. 4.4 and 4.5. This website is an astonishing work of scholarship.

All that was just the preamble. Here is a neat fact I stumbled across about a week ago, when I was just doodling triangles. It's nice because it connects the angle bisectors and the perpendicular bisectors.

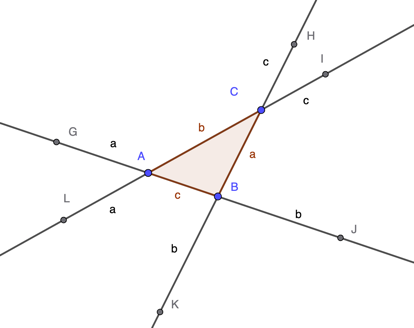

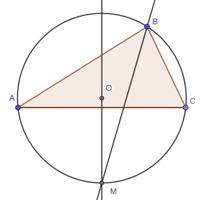

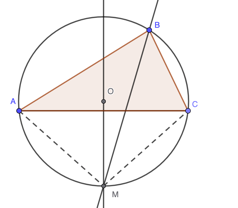

In a triangle the line bisecting an angle meets the perpendicular bisector of the opposite side at a point (M in the diagram below) that lies on the circumcircle.

This was new to me but I thought there ought to be quite a simple and accessible proof. But after a bit of head scratching, I couldn't see one, so I thought it must be a standard result, and looked it up. I did find a few proofs, but they were all more complicated than I was hoping (and at least one was wrong). The problem is discussed on Mathematics Stack Exchange but I still didn't find the "obvious" proof I was looking for.

After days of head-scratching I finally had my eureka moment! The proof I was seeking uses the following fact.

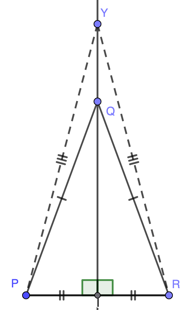

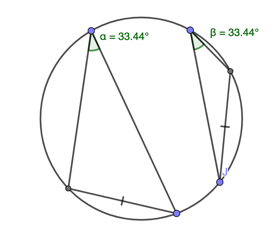

In a given circle, any two chords with the same length subtend (i.e.make) equal angles on the circumference. Here's an example:

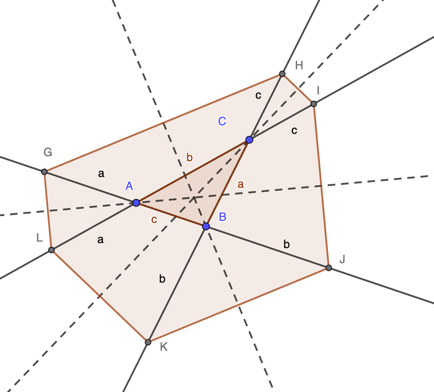

Now it's easy. Add some chords.

I claim that the line BM that joins B and the point M where the perpendicular bisector of AC meets the circumcircle is the line bisecting angle ABC.

Proof: Any point on the perpendicular bisector of AC is equidistant from A and C. So AM and MC are equal chords, and the angles ABM and MBC they subtend are equal, in other words BM bisects angle ABC.