If you Google "Six people at a party" you will get over a billion hits.

Many will be about a well-known puzzle that asks us to show that, if there at least 6 people at a party, there must among them either be 3 all of whom are mutually acquainted or else 3 who are mutually unacquainted.

This is a special case of Ramsey's theorem, named after the Cambridge mathematician Frank Plumpton Ramsey, who in 1928 published a semi nal paper, On A Problem Of Formal Logic. This was a very general result from which it can be deduced that, if a structure is big enough, then if you parcel its components out into groups there will always be groups containing large ordered substructures.

nal paper, On A Problem Of Formal Logic. This was a very general result from which it can be deduced that, if a structure is big enough, then if you parcel its components out into groups there will always be groups containing large ordered substructures.

However his theorem had nothing to say about what was "enough", and this combined with the fact that many particular cases are of great interest and often quite simple to state, has stimulated a huge body of mathematical research in Ramsey Theory, and also generated much interest amongst fans of recreational mathematics. Strikingly, after almost a century of investigation we only know exactly what is "enough" for some fairly small cases, and outside those we often have only some lower and upper limits, which in some cases are absurdly far apart.

Back to our party problem. This is one of the cases where we know the exact number, 6. The problem is easier to analyse if we step away from the party scenario and frame the question in a more abstract way.

Show that if we have 6 points and we connect every pair of points by an edge coloured either red or blue, then in the resulting diagram we will always be able to find at least one triangle all of whose edges are the same colour, either red or blue (we call these "monochromatic" triangles).

I hope you can see that this is essentially the same problem. To cast it in the language I used to outline Ramsey's theorem,

- "big enough" is 6

- the components being assigning to groups are the edges

- the groups are red and blue

- and the ordered substructures are monochromatic triangles.

There is a standard proof of this which is not too difficult and very nicely described in the Wikipedia article on Ramsey Theory (see R(3, 3) = 6, under "Examples"). However there is an alternative proof, due to Goodman[1], which shows amongst other things that with 6 points there are in fact at least not one but two monochromatic triangles, and gave a formula for the minimum possible number of monochromatic triangles if there are more than 6 points.

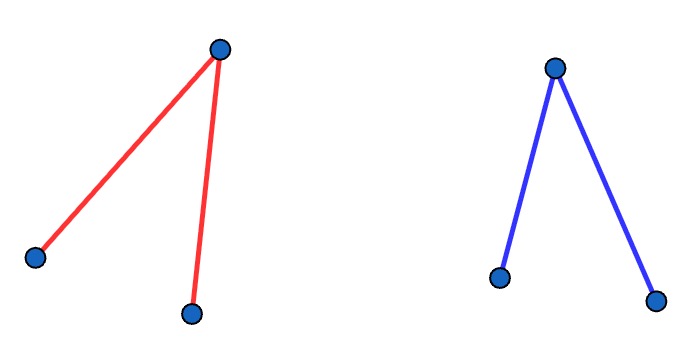

His proof uses a counting argument. Imagine we have coloured each the 15 edges amongst the 6 points either red or blue. We count the number of monochromatic paths of length 2 formed by two edges of the same colour meeting at a point, like those below, and we do so using two different methods.

Method 1 is to count by triangles. Amongst 6 points we can form 6 choose 3 = 20 triangles. A "bicoloured" triangle with side of both colours will only contribute 1 monochromatic path to the count, but a monochromatic will contribute 3. This gives a count of

no. of bicoloured triangles + no. of monochromatic triangles x 3

= total no. of triangles of both kinds + no. of monochromatic triangles x 2

and remembering that there are 20 triangles in all this gives

no. of monochromatic paths of length 2 = 20 + 2 x no. of monochromatic triangles

Method 2 is to count the paths by considering the edges that meet at each point. There are 5 at each point and there are three cases to consider

- All 5 edges the same colour. This will contribute 5 choose 2 = 10 to the count of monochromatic paths.

- 4 edges the same colour and the other edge different. This will contribute 4 choose 2 = 6 to the count of monochromatic paths.

- 3 edges of one colour and 2 of the other colour. This will contribute 3 choose 2 = 3 plus 2 chose 2 = 1, a total of 4 to the count of monochromatic paths.

Examining the possible contributions of 10, 6 and 4 we see the minimum possible is 4, and since there are 6 points we have

no. of monochromatic paths of length 2 ≥ 6 x 4 = 24.

Finally combining this with the result form Method 1 we find

20 + 2 x no. of monochromatic triangles ≥ 24

2 x no. of monochromatic triangles ≥ 24 - 20 = 4

no. of monochromatic triangles ≥ 2

which establishes the claim that there will be at least 2 monochromatic triangles.

It's conceivable of course that the minimum number of monochromatic triangles is in fact greater than 2. Can you draw a diagram to show this is not the case and that a configuration with only two monochromatic triangles is actually possible? Solution in comments.

[1] AW Goodman (1959). On Sets of Acquaintances and Strangers at any Party. The American Mathematical Monthly: Vol. 66, No. 9, pp. 778-783

Picture of F P Ramsey, Wikimedia Commons