Well, I have reached the halfway point in my study of science with the Open University - farewell, Book 4. I have enjoyed you very much, and I do believe that we have surprised each other.

You surprised me by re-introducing me to The Mole, and making me love it. I surprised myself by not only enjoying chemistry, but understanding it too.

However, I must put in a complaint. Not about the chemistry, you understand; nor about the way in which it was taught (although really, some of the writers need to embrace the idea of "less is more"). No, my beef is with those who set the questions for the TMAs (tutor-marked assignments).

In this case, the person who required us to needlessly rearrange an equation, then arrange it back again, when we could find the answer quite easily using the original equation and the information in the graph - thereby confusing everyone on the course - should be punished by being locked in a room with Silvio Berlusconi and Celine Dion being played on a loop.

Failosaurus.

But apart from that little blip, the TMA is done and dusted, and is going through a checking process. I should have dispatched it by the end of the day today.

I feel I've achieved quite a lot from this module: I understand, do not fear, and in fact have grown to love Avogadro's mole; I am able to write balanced chemical equations; I understand acids, bases and equilibrium; I can find the hydrogen ion concentration of a substance from its pH; and I am beginning to understand how drugs work (and therefore, how enzymes and hormones work). It's really fascinating stuff.

Fuel, and evidence, is being added to my mini-crusade against quackery. Well, my own personal local crusade, partially inspired by Ben Goldacre (I had my doubts before I started studying science, and before I discovered his Bad Science writings).

I should clarify: the placebo effect is real, and documented, and I'm absolutely happy with that. What really grates my carrot is when people peddle something like homeopathy as "science". Some homeopathic remedies are sold at a dilution of 200C. That means that one drop of the "remedy" has been diluted in 200 drops of water - 100 times over. It has been diluted more than the number of atoms in the entire universe. (Thanks to Bad Science for this nugget!)

And that is only one of the ways in which homeopathy is quackery.

But as I said - the placebo effect is fine. I have no problem with people parting with their hard-earned cash for nonsense, or for a placebo. What I DO have a problem with is quacks encouraging seriously ill people to stop their medication, and start taking sugar pills. That is dangerous, arrogant and pretty close to evil. I saw a forum discussion, via a tweet from Le Carnard Noir, in which homeopaths were talking about how to encourage HIV and AIDS patients to stop taking their retrovirals in favour of taking sugar pills.

And then one of them demanded that everyone else stop making a link between HIV and AIDS. That's not just deluded, it's dangerous. And vulnerable people, who are desperate, will listen to them.

I've also learned that when people say that, "Natural is better; chemicals are bad, m'kay" they have not really thought about what it is that they're saying.

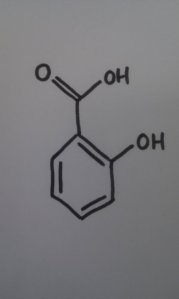

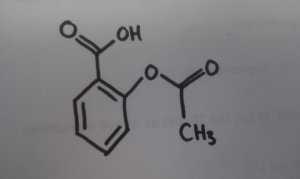

Take the example the OU gave us: aspirin was developed from willow bark, which has the active ingredient salicylic acid. In days of yore, willow bark was used to treat aches and pains, and was quite effective - except for the side effect of stomach irritation. Chemistry has enabled scientists to adapt the natural drug - salicylic acid - to acetylsalicylic acid, which does the same thing, but without the side-effects.

Another example is Ventolin (or to give it its proper name, salbutamol). It mimics adrenaline, a chemical released by our bodies in times of stress. As it happens, adrenaline is very effective at opening the airways, thus relieving asthma - but the last thing an asthmatic wants is increased heart rate, changed blood flow, and the jitters. Salbutamol was developed from adrenaline, but tweaked slightly so it only affects the lungs, without affecting the other organs.

The natural remedy was a great start; but most people forget (or likely don't think about it at all) that the plant evolved the chemicals for its own good; not for ours. Why would a natural remedy, "designed" to benefit the plant it came from, be ideal for use on humans with no tweaking?

Instead of bemoaning the work of modern chemistry, people should be celebrating it. It's an incredibly creative area of science, and has saved and improved countless lives.