Review of:

Lewis, Marc (2015) The Biology of Desire: Why Addiction is not a Disease Melbourne & London, Scribe Publications

The value of this book can’t be under-estimated and should not be dismissed. Its target is the biomedical model of addiction – the disease model – and its success as a book for me was to further clarify the slipperiness of the term ‘biopsychosocial’ common to contemporary discussions of the aetiology, maintenance and the structuring of supportive interventions in addictions. My background in social work was an early attraction to the term ‘biopsychosocial’ as a means of bridging the divide in the debate between biomedical and psychosocial theories of addiction. However, in practice, this bridging tended to further bolster the biomedical model and relegate psychosocial intervention to a secondary role both in specialist intervention team structures and operations. Such teams often continued to be headed by a psychiatrist.

This for two reasons (although these reasons are solely the product of a retired practitioner’s reflections on past experience):

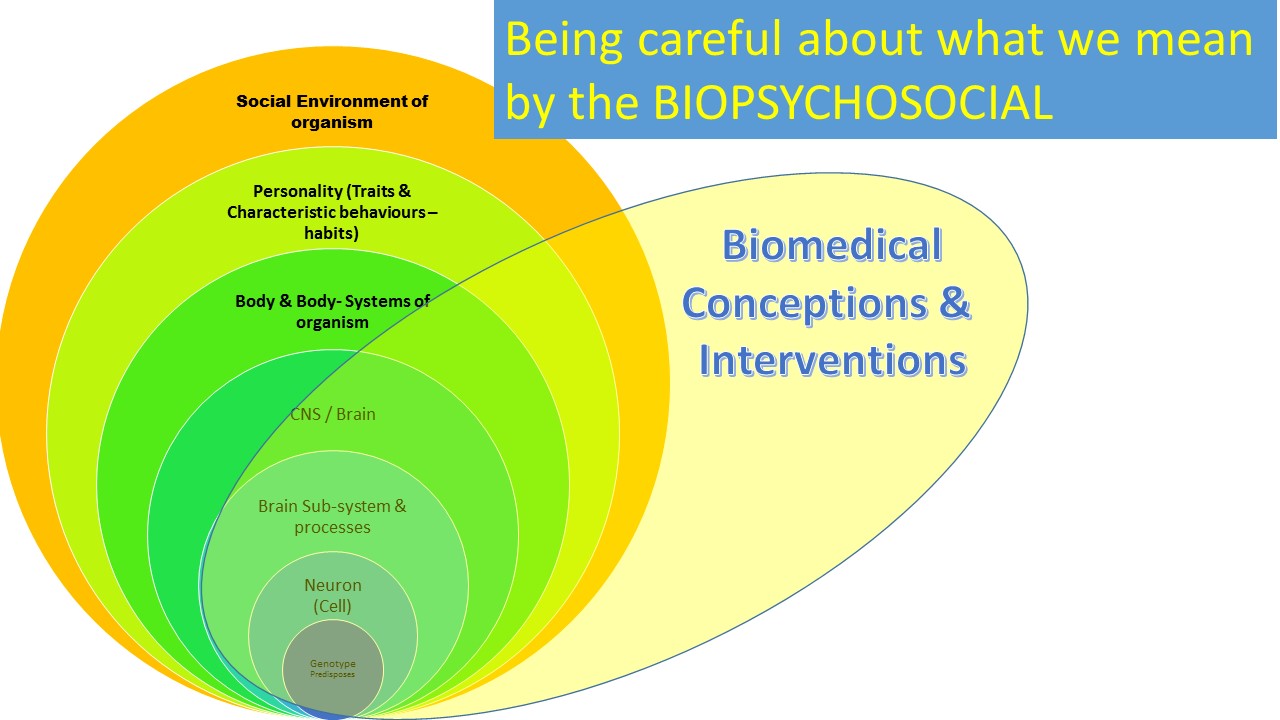

1. The ‘bio’ in the biopsychosocial was often regarded as essentially focused conceptually and owned therapeutically by biomedical sub-teams.

2. Biomedical sub-teams increasingly colonised the psychosocial and, in doing so, gave them a medical flavour, especially at the level of qualification to practice and demonstration of that qualification in role and appearance.

This feature is, of course, in part a product of institutionalised state health providers and less apparent therefore to Lewis in the USA, where the biopsychosocial is conceived as somewhat apart from the biomedical model. In his book, the 'bio' in biopsychosocial is a merely the name of organisation of a knowledge of embodied systems and is much easier to pit against a biomedical system that is essentiall run for profit.

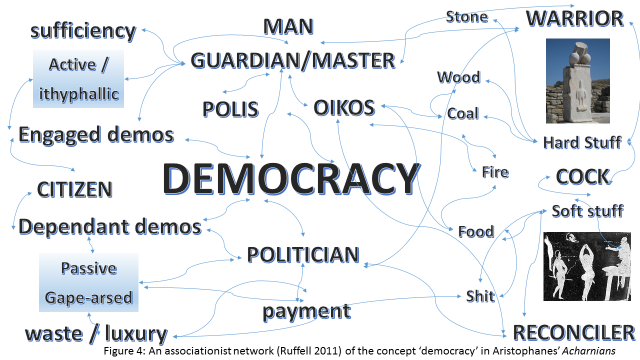

I tried to draw this distinction in the following figure.

In the figure, the biomedical merely occupies the same terrain as a conceptual biopsychosocial model but it interprets that terrain differently – through the lens of qualified and exclusive practice. Any realistic understanding of that figure will, of course, readily admit that there will be a trade between the biomedical and conceptual biopsychosocial but that both need to be kept distant in our thinking, at least at the level of theory and intervention planning. As Lewis shows, some descriptions of neuronal activity can describe change in neurobiological and neuroanatomy in terms other than ‘disease’ and can make legitimate analogy between the features of socially validated and socially invalidated learning.

Thus while the life-processes in the life of a ‘junkie’ are seen now as best described in arcs of ‘recovery’ from a deficit position, the processes involved in falling in, and out of, love and learning literature or neurobiology are seen as ‘normative’ learning processes. Yet all these processes can be described throughout the nested processes shown in our circular system set in the figure above. For Lewis, given free reign and dominance, the biomedical (even when it imports and colonises aspects of the psychosocial) retains interests that are solely its own – those of professional exclusiveness and top-down control of the person experiencing learning through addiction. His stories of the horrors of treatment centres ring so true to me from my working life (p. 212) - although that is not to say I didn't see islands of good personal practice.

One sign of the difference in the way the biopsychosocial is conceived in Lewis is the Birmingham Reach Out Recovery (p. 214) intervention in which a large part of the intervention was fuelled by consulting groups of former addicts who worked with each other to socialise and increase access to support. Often that support appears little less than avenues and ‘recovery-friendly shops’ for the ‘addict’ to build on and generate new story from their old stories, stories which appear to have got stuck in 'now-appeal' as he calls it. That this is more truly biopsychosocial, Lewis argues, is seen in the deficiencies of time and professional personnel controlled CBT and even mindfulness interventions that measure input and output but do not generate motivation or change (in themselves). The stress is on narrative (I can see the biomedical teams now developing training for nurses in ‘narrative therapy’ - indeed it has been happening some time) but not narrative aimed at 'therapy' as such but in generating motivated movement in the stalled neuroplasticity in the brain of the addict (locked into what Lewis call ‘now-appeal’).

So if desire cannot be turned off or seduced away from addictive goals, then it has to be fastened to goals incompatible with addiction – goals such as freedom from suffering, achievement of life projects, access to loving relationships, and the sense of coherence and self-love that can come with abstinence. And if those goals cannot be envisioned, because of a static pre-occupation with the present, then self-narrative and desire need to be packaged together – self-narrative to shift perspective to long-range goals, desire to power the pursuit of these goals.

Stories don’t work without emotional themes. They would be impossible to follow. ….

This (from a neuro-scientist) is now conceivable because neuroscience, unlike the sterile discipline of cognitive psychology, has freed itself from a merely cognitive and merely behavioural interest – its interest in those brain processes called emotion and drive would have shocked Skinner, Pavlov, and Beck. Now no-one dare write about psychology without recognising ‘Descartes’ Error’ (Antonio Damasio).

So this book genuinely revels in all its centre parts on biographical (and some autobiographical), stories of addiction that are a long way from the mechanical nature of the Jellinek curve. Its bookend chapters are helpful though with definitions of brain anatomy and processes that can be understood by anyone – and while this book can replace no textbook accounts for a learner in higher education, it can make their limitations and gaps clear to both pure scientists and practitioners: pure science, that is, which is not still married merely to positivism. Look for instance at the genius of the everyday science explanation of the anatomy and function of the Orbito-Frontal Cortex (p. 82). If you are a beginning learner (or even if you began a whole ago) you can learn a lot from that.

I love this book.

Steve

The

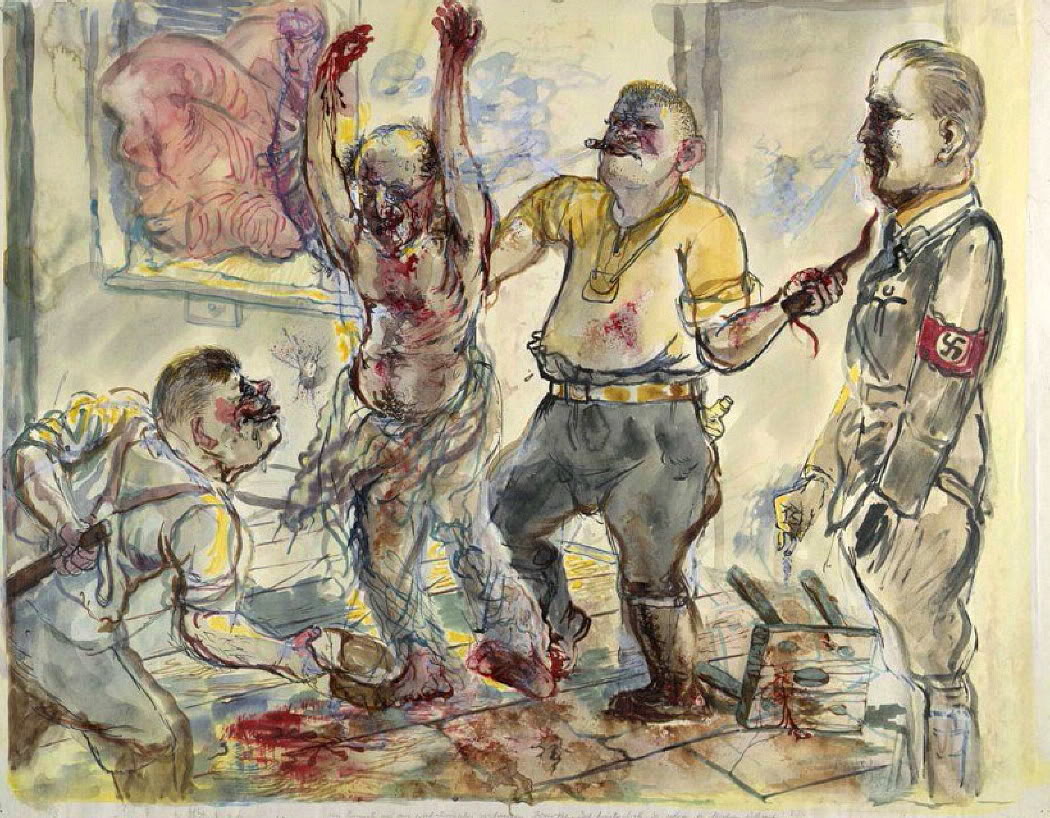

reality of anti-Semitism as an enforced aspect of Jewish identity is as evident

here as in the more appalling exhibits that paint a permanent record of the

Holocaust such as Grosz’s (1938) ‘The Interrogation’ where Jewish flesh softens,

quavers and bleeds against the brittle hardness of an appalling interrogation

or Herman’s (1941) saga of the flight of Jewish families during the Warsaw night

(under the appalling dominion of a black cat devouring a mouse as it stalks

roofs smaller than itself.

The

reality of anti-Semitism as an enforced aspect of Jewish identity is as evident

here as in the more appalling exhibits that paint a permanent record of the

Holocaust such as Grosz’s (1938) ‘The Interrogation’ where Jewish flesh softens,

quavers and bleeds against the brittle hardness of an appalling interrogation

or Herman’s (1941) saga of the flight of Jewish families during the Warsaw night

(under the appalling dominion of a black cat devouring a mouse as it stalks

roofs smaller than itself.

Etty’s nude wrestlers contrast black and white skin and

flesh in a moment of male combat where other meanings emerge – even changes in

skin colour as a white man’s embrace recolours the skin of an encircling arm (a

trick of light or of meaning). We see all that differently again in a wonderful

study of male flesh in animated combat in Steve McQueen’s Bear (1993) where

every meaning and attribution of the significance of flesh is dramatically

tested as action morphs aggression and predation into balletic dance, as light

turns flesh colour and surface into many forms, merely by the act of looking from

multiple perspectives.

Etty’s nude wrestlers contrast black and white skin and

flesh in a moment of male combat where other meanings emerge – even changes in

skin colour as a white man’s embrace recolours the skin of an encircling arm (a

trick of light or of meaning). We see all that differently again in a wonderful

study of male flesh in animated combat in Steve McQueen’s Bear (1993) where

every meaning and attribution of the significance of flesh is dramatically

tested as action morphs aggression and predation into balletic dance, as light

turns flesh colour and surface into many forms, merely by the act of looking from

multiple perspectives.

A bronze Marco

Cavallo still exists in the city but people have forgotten its significance. It

graces the university grounds where once the ‘mad’ were incarcerated – locked

in closed wards and often living in their own faeces, subjected to treatments

that seem to us now, and did to the inmates then, like torture. One of the

first small steps in the movement, started by Basaglia in Gorizia, an asylum on

the Yugoslav border, was stopping the tying of children who had been labelled

‘insane’ physically to their chairs or beds. And here is the politician,

Tommasini’s (one of the first to reject the idea of anything less radical than

asylum closure), first visit to the asylum in Perugia:

A bronze Marco

Cavallo still exists in the city but people have forgotten its significance. It

graces the university grounds where once the ‘mad’ were incarcerated – locked

in closed wards and often living in their own faeces, subjected to treatments

that seem to us now, and did to the inmates then, like torture. One of the

first small steps in the movement, started by Basaglia in Gorizia, an asylum on

the Yugoslav border, was stopping the tying of children who had been labelled

‘insane’ physically to their chairs or beds. And here is the politician,

Tommasini’s (one of the first to reject the idea of anything less radical than

asylum closure), first visit to the asylum in Perugia: