Image courtesy of https://unsplash.com/@zoshuacolah

I find myself at a crossroads when it comes to modern children's literature. As I sit with memories of my own childhood, I can't help but reflect on the books that shaped my early years—tales like Peter Rabbit, Pinocchio, Heidi, and the magical world of One Thousand and One Nights and adventures of the Secret Seven. They transported me to places where innocence reigned, where good triumphed over evil, and where the harsh realities of life seemed distant, wrapped in a cocoon of adventure, fantasy, and moral lessons. These stories left me with a sense of wonder and a belief that the world, while sometimes dangerous, was ultimately a place of hope.

But today, the landscape of children’s literature has shifted. It seems that the stories now available to young readers reflect the increasingly complex and, often, darker world they are growing up in. Books addressing issues like parental depression, alcoholism, bullying, and even abuse have found their way onto the shelves. I wonder: is this a healthy evolution, preparing children for the world they will inevitably face, or are we stealing something sacred from their formative years by exposing them to the darker sides of human experience too soon?

On one hand, there’s an argument for realism. Today’s children are, by no means, insulated from the difficulties that life can bring. Many are growing up in homes where they are already exposed to struggles far beyond their years—be it financial hardship, mental illness, or broken family dynamics. These books, which dare to tackle such themes, can serve as a mirror to their own experiences, offering them characters who understand their pain and challenges. Literature like this might provide comfort, reminding them they are not alone in their struggles. It can open up conversations, allowing children to express what they may not yet have the vocabulary or the courage to articulate on their own.

Moreover, proponents of this modern wave of children's literature often argue that it equips young readers with emotional intelligence. They learn empathy by seeing the world through the eyes of characters who face adversity. They develop a sense of resilience when they witness how those characters persevere. After all, isn’t the role of literature, at any age, to help us make sense of the world?

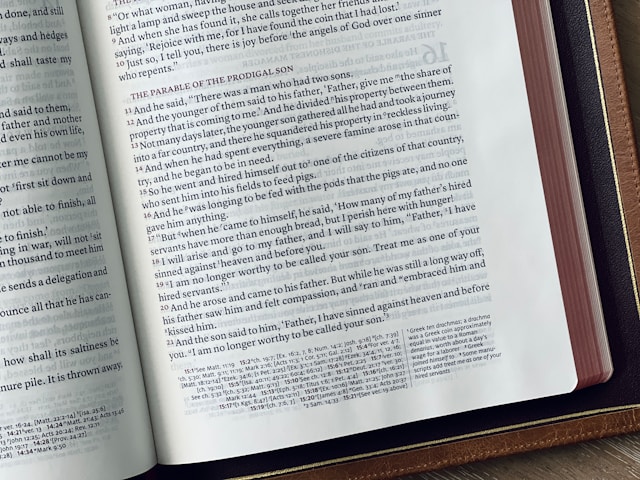

Yet, despite these potential benefits, I can't help but feel an internal tug towards protecting a child's innocence. There is something sacred about the untainted imagination of a child. When I recall the tales of my own youth, I remember how they nurtured a sense of safety and possibility. They offered an escape from any unpleasantness that might have been lurking in the real world. Stories like *Heidi* gave me hope that no matter what misfortunes might befall us, kindness, faith, and goodness would always win out in the end. Such books may not have reflected the darker realities of life, but they preserved something I think is often overlooked in today’s fast-paced, hyper-connected world: the joy of simplicity.

There’s an unspoken magic in a child’s early years, a fleeting window of time where the world can—and perhaps should—remain a place of wonder, free from the weight of adult worries. When we introduce stories about broken families, mental illness, or addiction, are we asking children to grow up too quickly? Are we taking away their opportunity to experience a world that, for a short time, is filled with wonder and delight? There’s a purity to those early days that seems too precious to tarnish with the harshness of reality. Does a seven-year-old need to understand the complexities of addiction or depression? Can’t they just have a few more years where the biggest challenge is whether Peter Rabbit will get caught in Mr. McGregor's garden?

And yet, I see the counterarguments too clearly to dismiss them. The world has changed since I was a child. Children today are bombarded with information, with or without our consent. Technology and media have stripped away much of the protective veil that once shielded childhood from the more distressing aspects of life. Perhaps, in this context, stories that reflect the struggles of modern life can provide children with tools to navigate the world they’re already part of.

But the dilemma remains. Should children be exposed to these realities through literature, or should books be a safe space, preserving the innocence of youth for as long as possible? I don’t have a clear answer. Part of me leans towards the belief that childhood should be a time of simplicity, where joy, wonder, and imagination are at the forefront, allowing children to build a foundation of hope before they face the inevitable challenges of life. Yet, another part of me wonders if we do them a disservice by shielding them too much, by failing to prepare them for the very real difficulties they will face as they grow older.

Perhaps the balance lies somewhere in between. Maybe there’s room for both—stories that preserve innocence and wonder, alongside those that gently introduce the realities of life. As I ponder this, I find myself still searching for that elusive balance between protecting a child’s heart and equipping their spirit for the world they must one day navigate. Perhaps it’s a question that each generation must answer for itself, as we navigate the ever-changing landscape of both childhood and literature.