Martin Weller: ten digital scholarship lessons in ten videos

The greatest quality of a Martin Weller lecture is that leaves so much unsaid and unexplained. This isn't a fault of the lecturer, rather it is either his personality to take an answer so far, to ask questions and then to leave question marks of various shapes and sizes hanging there. Your mission, if you care to take it, is to go and find answers.

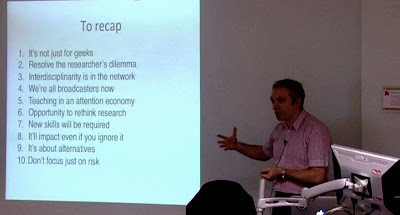

In this talk, or presentation ... or seminar (responding to questions afterwards lasts as long as the talk itself) Weller considers what it means to be a digital scholar, and in relation to H818 addresses the benefits and pitfalls of being open.

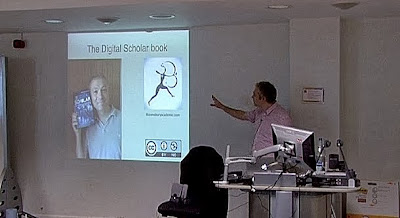

He begins with his book 'The Digital Scholar'.

You can buy it - it's a book and an eBook. You can also download it for free. Its creative commons copyright also permits you to distribute it, attributed, even to mash it up i.e. to play around with it. I do - often. I Tweet it line by line, grab pages and annote with text and graphics. I try to bring the pages to life, to re-animate the dead. Which is the problem all books have - certainly compared to anyone used to the attraction of interactivity and mulitmedia and multi-sensory 'sit forward' content.

Privacy and online pressence

Do what works for you in different situations - there are many degrees of openness. The pay-off of pressence is enegagement, is to gravitate towards and to be a magnet for like-minds. Weller doesn't say it, but the best thing you can do online is to ask for advice and to know where to do this - in the right forum you will find an expert with the right voice, tone and techniques of explanation just for you. I have been taken by the openness of Amanda Palmer and her philosophy of knowing what she wants and asking for it.

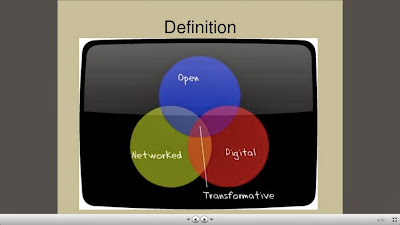

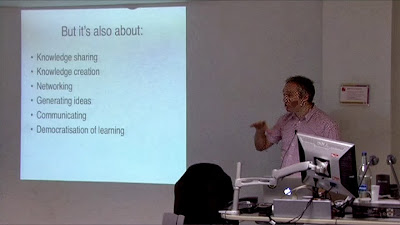

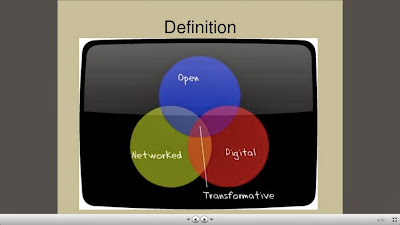

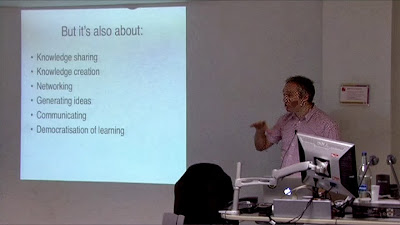

Scholarly practice in the digital domain means:

And it is, according to Weller, the intersect between openness, digital and networking were transformation occurs. I'd go further than this and put this Venn diagram in an unexpected context - not 'out there', not 'here' but rather between regions of your brain. It changes you. Those parts of your that you share, that you are open with, through the quasi-omnipresence of your digital being as it is networked, as connections form - as they do at home, around you with your friends and colleagues, so it creates new and otherwise unlikely tingles of response and activity in your brain. It is neurological.

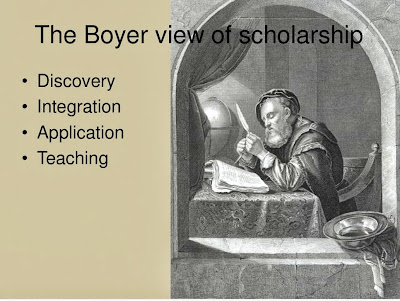

Scholars have been there defining what scholarship is. However much I look at these guidelines and lists, as though they are prerequisites to get into grammar school and take a degree, I think rather of 1901 and possibly still 1911 Census Returns where anyone attending school is defined as a 'scholar'. The act of being engaged in learning makes you more scholar than anyting else - the potential was there even if it was stymied when kids left school armed with the basics at age 14.

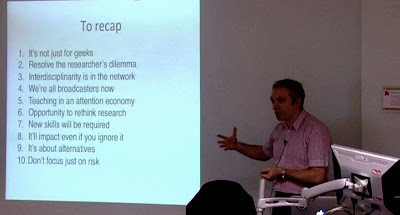

Wherein lies the problem. Weller says ten years, his peer group gives it longer, for the 'digital scholar' to emerge. I have argued that the digital scholar is imminent. I would now say that in time, retrospectively, we will identify people who already are the digital scholars - the 18 year old how schooled law graduated recently called to the bar, the 14 or 15 year old who has drilled through academic research to come up with his own viable solution to a medical issue ... the academic communtiy won't accept it for the very reason that they ONLY see scholarship as it is defined and won through traditional, conservative, tightly controlled levels. The digital scholar will transcend these ... people will simply appear, professor-like in all but name, as a result of the root they have taken into a subject that circumvents the 'required' pathway.

Gobbledygook it may be ... but there are what we would understand to be quite normal conversations that plenty around us may have little understanding of. Those brought up in a digital world have always been familiar with its architecture - it just IS, like houses and trees. Whereas we - most of us anyhow, knew what the landscape looked like before. We have seen the bits and pieces, sometimes do disassembled as to make little sense and we have witness the folly and false starts too and the many white elephants.

My niggle with any presentation that quotes somebody is not having the reference. Several hours of searching and I have found only some of the authors quoted and in the case of Waldrop above I can find him, but have no idea where he said it. This matters more to me than ever now, not simply because the level of engagement with the subject that I have reached, but because I expect there to be links and I expect the answer to be a click, and therefore a momentary glance away.

I cannot find Le Muir anywhere. This despite having read more than most on blogging over the last decade. To blog is interesting because the reality is that only a fraction of us take to it ... the teenager who kept a diary will make the best blogger, it's part of you. Now the academic community is beginning to expect the 21st century scholar to blog - to have a digital presence, to wear their research on their sleeve, to become like a special edition iPad or iMac, with a see-through skin. We don't care what you are like, but let us see all the same.

Weller compares before and after slides in relation to the blank with an OU logo and these colourful visualizations. He shows up a failing though. Someone who is good with words may not be able to visualise their thoughts - simply repeating a word in many fonts or creating a Wordle does not in any way complement or enhance the message. Advertisers discovered the answer in the 1960s - you put an art director and copywriter together. How can we get more of that in education? When I see and listen to academics I almost always see a group of strangers who happen to be in the same room. Even or especially in a jointly written paper I don't see how or where the collaboration has occured. It's not as if they are team behind a TV series, each person with a role so clearly defined that it has a title. That'll be the day. It would require the 'digital scholar' to become the equivalent of the producer or director with others taking part having clearly defined roles. As happens, for example, in a product trial.

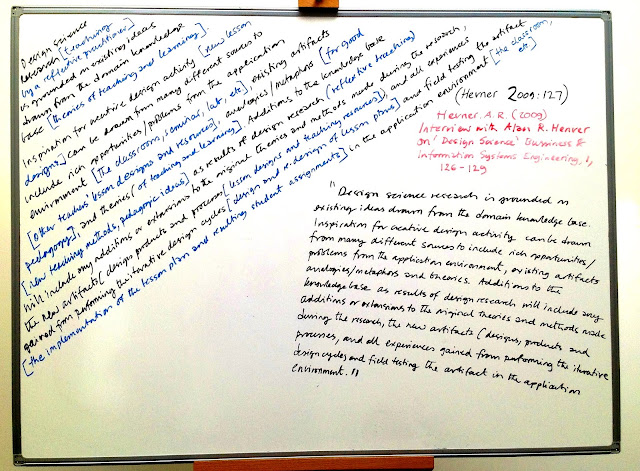

I would also question screen grabs as a way to illustrate anything. I'd far prefer that anyone picks up a pen and does a doodle that expresses what they see in their heads - this after all is closer to the meaning the author is trying to put over.

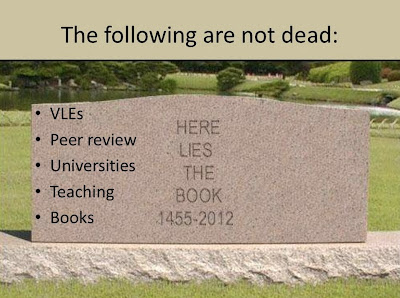

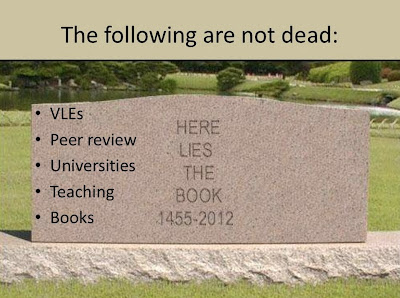

I will return to this moment repeatedly - I admire Weller and those academics who with determination stay on the platform and observe the world as it passes by rather than pandering to the futurologists and revolutionaries who think that we have to sweap away what went before rather than build on it and work alongside it. The first newspapers was printed on the 6th November 1605 - they've survived this far. Their savour might be augmented reality.

I particularly like the above. I gave a few weeks of my life to writing a scaving book review of Nicholas Carr and 'The Shallows' and then supporting my perspective in a thread that emerged in the Amazon reviews. Perhaps I need to go a few rounds with Lanier and Turkle too then accept that a Master's education means that I will never stand, virgin-like, infront of authors such as these and offer them my body and soul. They are journalists, popularist, scaremongering, plausible and always wrong.

This grab from an animation by David Shriver might be a life-changer - taking me back to a way I did things a couple of decades ago. I just got on with it. Something that is going to work big one day, has to work small first then multiply. I keep itching to start a lecture tour - I have the projector and lecturn. I know what I want to talk about. I need to book a venue and get on with it.

I agree with the above with an important caveat:

What has become self-apparent to me during the course of the last few years studying online education, and 'education' is that human beings are extraordinarly diverse. However much we see ourselves as part of a race or community or cohort or class, we are ultimately very alone in our uniqueness. What ever impression you get, say of tens of thousands in North Korea doing drills together in a stadium, they are, each of them, their own person. One of the most wonderous human traits is the contrarian - even against inclination they will do the opposite so as not to be the same. I particularly like the idea that 'not learning' should be see as an educational theory. It's true - keeping your sheet blank while everyone around you takes notes is an approach. Not learning means that you stand still, or go somewhere else while the conveyor belt of the class moves everyone else forward (though in different steps).

See the 20th March 2012 Lectures at LSE here.

Notes attached as a PDF.

I'm keen to expand on these notes. To fill in the gaps. To find the precise place where Weller refers to what someone has written.

Next step is cutting and pasting this into my external blog. Then spitting it out in bits as and when required. And nailing the references. A couple of clicks and I not only found the reference to John Naughton, but I'd bought his book. 90p on Kindle.