Linearity of Expectation can pop in surprising places.

Buffon's

needle is a famous experiment first published by the Comte de Buffon in

1777. His idea was to repeatedly throw a short needle on to an array of

equally spaced parallel lines and count how often the needle crossed a

line. This can then be used to estimate the value of the famous number π, a rather

surprising fact.

Suppose

the lines are spaced 1 unit apart and the needle is of length L less

than 1, so the needle will cross at most one line. Then it can be shown

the average number of crossings is 2 x L/π.

The standard way to work this out uses calculus, but reading around Linearity of Expectation I came a cross a far simpler way.

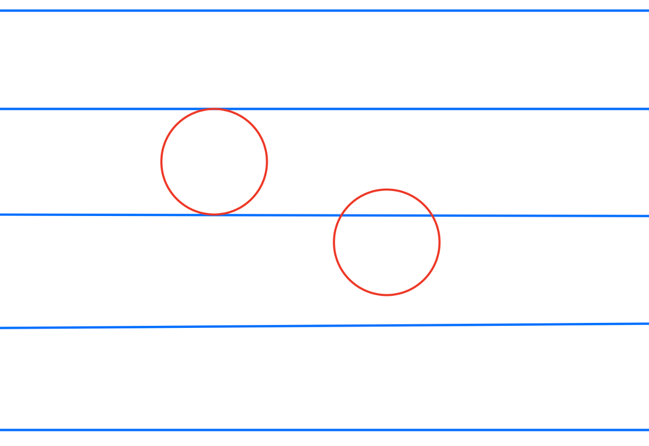

In the sketch below the circles

are of diameter 1 and you can see that a circle however

positioned will have exactly 2 points in common with the array of

paralle lines.

So we can say immediately that the expected number of

crossings when a circle is placed on the array of parallel lines is 2.

Now imagine replacing the circle with a polygon made up of many tiny needles each of identical length L. The polygon will only be an approximate circle, but if the needles are very short the approximation will be good.

Given the circle has diameter 1 its circumference will be π x 1 = π and the approximating polygon will require π / L needles. Suppose we define an indicator which is 1 if a given needle crosses a line and 0 otherwise. Let the expected value of this indicator variable be E. This is the same for all the needles; it represents the average number of crossings, not the actual number of crossing by any particular needle.

Using linearity of expectation and adding this expectation E across all the π / L needles we get E x π / L and this must be the expected number of crossing for the circle, because the needles taken together make up the circle! So E x π / L = 2.

Rearrange this slightly and voilà! - we have Buffon's formula.

E = 2 x L / π

This extremely neat and simple approach was found by Barbier as long ago as 1860 but I only stumbled across it a couple of days back.

We need to do a little more work before we have a complete proof, because we've assumed L is very small. What if it's not? I'll add something in the comments about this.