Personal Blogs

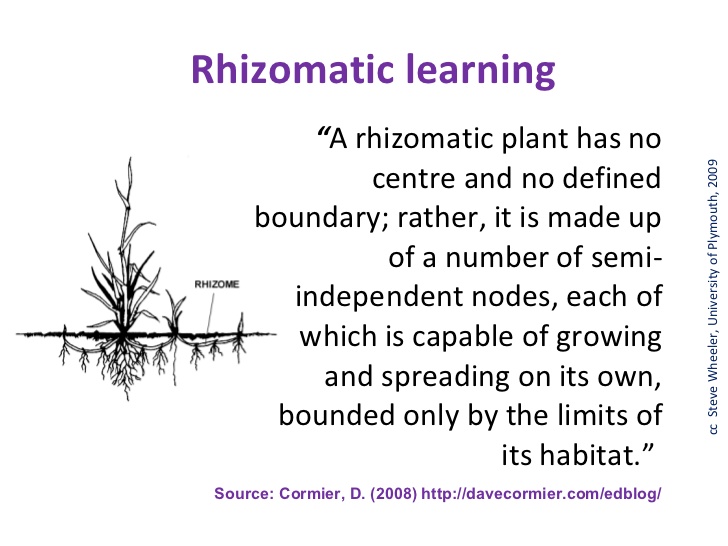

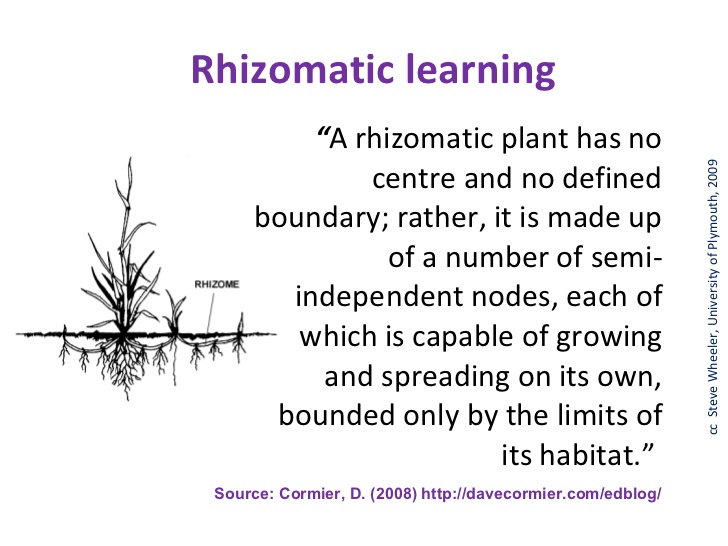

My first thought when coming across the concept of rhizomatic learning was to try to distinguish it from connectivism, whilst recognising the things they had in common. I came to the conclusion in focussing on the rhizome metaphor, that the former centres even more on the process than the product of learning when compared with connectivism, to the extent that learners themselves are seen as the curriculum - they decide the learning goals and the journey to those goals is a large part of what is studied.

Describing rhizomatic learning, Cormier (2008) writes:

Could I imagine implementing rhizomatic learning?

How might rhizomatic learning differ from current approaches?

Image source: Wikimedia commons

Implementing connectivism: reflections on a course design

After posting several blogs on my experience on open courses on my course where we explore the vision, purpose, and challenges as well as the benefits of open learning, I want to express my views on how I would go about implementing it in practice. At the moment, all of my teaching is online because of the lockdown. In my teaching context, online learning is meant to be in full effect. However, it is far from open learning, where students in principle would be more involved in knowledge creation and setting learning objectives. It is perhaps even further away from a connectivist approach (Downes 2005; Siemens 2005). Its principles, which are widely accepted as being generalizable to any connectivist learning context are summarised by Siemens (2004).

Connectivist Principles

I express my interpretation of the work of Siemens and Downes in a course I devised that takes a strong conectivism approach, based on some key principles devised by Siemens:Learning and knowledge rests in diversity of opinions

Learning is a process of connecting specialised nodes or information sources

Learning may reside in non-human appliances

Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known

Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning

Ability to see connections between fields, ideas and concepts is a core skill

Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities

Decision making is itself a learning process

Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality

For each activity in my course, I state how the principles set out above are realised.

My course is illustrated in a SWAY presentation found here:

Digital Skills for connective learning

Reflections on the Implementation

Because my outline of a digital skills course with connectivist elements in it is just an outline, it lacks details about the different ways I would encourage participants' critical reflection and how they would be able to explore concepts of currency in a fast-changing world. For example, they would be required to justify their choices of sources of information, the extent to which they can be sure about any assertion they make based on a source or sources and how relevant a piece of information is in their learning context and in today's world. They would need to demonstrate an ability to check 'information' and not simply take it on face value. To analyse concepts on several levels and from different perspectives. The problem with implementing such a course is that in its purist form, learners adopting a connectivist approach will be looking at a topic very much based on their own perspective. It would be difficult to tap into individual mindset in order to give feedback (like a tutor does where tasks and the direction of the course are set and controlled by the tutor). It does, however, allow for plenty of asking of critical questions like the above. The concept of connectivism isn't just useful in my opinion. I think in many cases it really should be the basis on which we plan and facilitate learning. Perhaps not in my (K-12) teaching/learning context, however, where not all but many students are used to more passive deferential form of 'learning'. They see the teacher as the font of knowledge - the one who not only directs learning but defines it in terms of 'knowledge', 'facts' or 'information'. As an example, they even ask permission to speak, even when asked to express themselves freely. For many of them, connectivism would be in conflict with the traditional concept of a course, though it is still possible to get them to enjoy task-based, self-directed learning. At their developmental stage, however, they are not quite 'world-wise' enough to know how to use that 'power' responsibly. It wouldn't deter me, because part of the exercise is about enabling them to acquire that needed experience. This kind of course, when applied in its purist form would suit older teens and adults, who know better what their professional and academic aims and challenges are.

Rhizomatic Learning

I do look for opportunities, however, to create and manage courses at least partly based on connectivist principles. And right now, when ALL teaching is online because of COVID-19, is an ideal opportunity to be more experimental. The current educational climate may be a great time to explore the rhizomatic learning (Cormier 2008) strand of connectivist thinking. Here, the focus is even more on the process more than the product, when compared with connectivism, to the extent that learners are seen as the curriculum - they decide the learning goals and the journey to those goals is a large part of what is studied. describing rhizomatic learning, Cormier (2008) writes:

'A rhizomatic plant has no centre and no defined boundary; rather, it is made up of a number of semi-independent nodes, each of which is capable of growing and spreading on its own, bounded only by the limits of its habitat' (Cormier, 2008).

Anyone can experience what this means by reading about it on Cormier's blog site, Rhizomatic 15 where he offers some real-life insights open courses. d106 facilitated by Jim Groom contains some elements of rhizomatic and connectivist learning.

References

Cormier, D. (2008). Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 4(5), 2. http://davecormier.com/edblog/2008/06/03/ rhizomatic-education-community-as-curriculum/

Downes, S. (2005) An introduction to connective knowledge in Media, Knowledge & Education: Exploring new Spaces, Relations and Dynamics in Digital Media Ecologies, Theo Hug (editor) 77-102 Jul 08, 2008. Innsbruck University Press

Siemens, G. (2005) Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. ASTD Learning News, 10(1), pp.1-28.

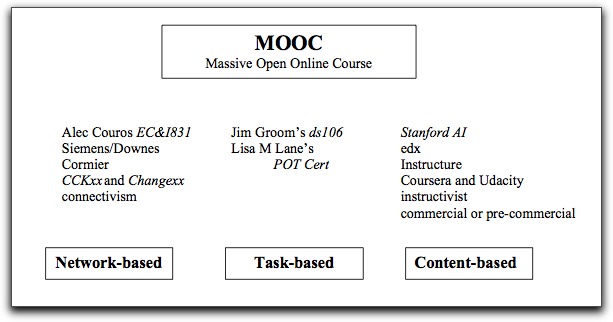

image source: Lane, L.M. (2012) ‘Three Kinds of MOOCs

Comparing MOOCs

Even in the last five years, definitions of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) have evolved. I say definitions because I think it is widely agreed that there are different types of MOOCs, serving different purposes for the users and for providers. Originally, since the early part of the 21st century (though some will argue that MOOCs existed before then), most observers could probably agree that a MOOC was a course provided through an online platform, using tools such as videos, and discussion forums, and with the emergence of web 2.0 apps, the ability to integrate with social networks. Some of the main characteristics of a MOOC were that they were often provided free, open to anyone and were offered by internationally known institutions or their faculty and did not offer a formal accreditation system.

cMOOCs (including task-based and networked-based)

Prior to 2015, we had seen the emergence of two major strands of MOOCs: cMOOCs and xMOOCs. The theoretical basis of cMOOCs was seen as “connectivism, openness, and participatory teaching” (Jacoby, cited in Veletsianos and Shepherdson 2016, p. 199- 200), emphasizing the active part learners play in knowledge creation, through their connections with other learners and their learning environment via networks facilitated by online technology. Canadian researchers George Siemens, Stephen Downes, and Dave Cormier based their MOOCs on the connectivist principles that everyone should determine their own learning goals, and structure and manage their own learning via personal learning networks. The learner is free throughout the whole learning process. These principles are still followed through in the task-based (Lane, 2012) MOOC, d106 facilitated by Jim Groom and Rhizomatic 15 by Dave Cormier, both supported by leading lights in connectivism theory. Cormier describes Rhizomatic as ‘a story for how we can think about learning and teaching’ where the learning community is the ‘curriculum’ or ‘challenge’. He asks participants to think of the learning environment as ‘’a research lab’, in which where participants are ‘researching along with me’. In terms of technology, the emphasis on social networking tools is clear when he talks about his communication with learners: ‘I’ll post it in the newsletter, I’ll tweet it … I’ll post it in the Facebook group and I’ll post it on the course blog.’ Similarly, d106 is described as 'Digital Storytelling’ where ‘you can join in whenever you like and leave whenever you need’ and describes how they ran a course ‘where… there was no teacher’. Communication is via a blog feed. Due to their open nature (where is no set ‘curriculum’, learners define ‘success’ and learning path, it is difficult to formally assess a learner’s progress and therefore to acquire monetary gain from these types of MOOC.

xMOOCs (including content-based)

In contrast to cMOOCS, xMOOCs follow a cognitivist-behaviourist approach (Hew & Cheung, cited in Veletsianos and Shepherdson 2016, p.199) resembling ‘traditional teacher-directed course[s]’ (Kennedy, cited in Veletsianos and Shepherdson 2016, p.200). The number of xMOOCs delivered has been growing rapidly, whilst any cMOOCS that still have some connectivist aspects to them (use of social media, group tasks) have adopted more and more of the features of xMOOCs (a fixed content is ‘delivered’ – hence the term content-based), to the extent they can be called hybrids. The UK company FutureLearn, for example, offers free, open MOOCS but its platforms are also used to promote fee-paying degrees with The Open University, microcredits and badges and the courses are structured by Futurelearn to quite a large extent. FutureLearn’s free courses also offer ‘extra benefits’ for a price, so students can gain extended access to materials. None of these are offered for a fee on the cMOOCS discussed above, as any course benefits are extended free of charge. The ‘open’ aspect on Futurelearn courses is more about students’ freedom to study at their own pace, than on unfettered access to materials. In terms of technology, however, Futurelearn has a more varied offering. On its online educator course, students use video, interactive quizzes and polls that are a fixed part of the course offering, as well as various social media that are used on the cMOOC courses, ds106 and Rhizomatic.

In 2020, there are more than 900 universities around the world offering over 11,400 MOOCs and the emphasis is on monetary gain – accounting for the emphasis on a cognitivist-behaviourist, where institutions can ask for payment based on the learners’ achievement of specific goals. So, whilst, d106 and Rhizomatic, offering free courses, make very little money each year, by contrast, Coursera's 2018 estimated revenue is around $150 million and FutureLearn made around $10million. This means there is a corresponding focus on formal accreditation of learning. Perhaps partly for the same reason, the concept of free and openness, very apparent in former approaches to MOOCs, has now evolved to mean anyone can apply from anywhere. More and more courses are asking for formal proof of prior learning, such as a diploma or degree and fees are being charged in return for globally recognised certificates. However, the term ‘open’ has always been defined differently by different observers. FutureLearn course, I can speak to all aspects of one of its MOOCs.

Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2014). Students’ and instructors' use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educational Research Review, 12, 45.

Jacoby, J. (2014). The disruptive potential of the massive open online course: A literature review. Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning, 18(1), 73-85.

Kennedy, J. (2014). Characteristics of massive open online courses (MOOCs): A research review, 2009–2012. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 13(1), 1–16.

Lane, L.M. (2012) ‘Three Kinds of MOOCs’ Blog. [Online]. Available at http://lisahistory.net/wordpress/musings/three-kinds-of-moocs/ (Accessed March 29, 2020)

Veletsianos and Shepherdson (2016), A Systematic Analysis and Synthesis of the Empirical MOOC Literature Published in 2013–2015.

Connectivism, EAP and ESOL Teaching/Learning

My best way of analysing and critiquing connectivism, whether as a pedagogical principal or as a learning theory is through the lens of my own learning and teaching. First, my teaching. I am an EAP and an ESOL teacher. For most of my learners, the content they learn (I am thinking of EAP primarily when I speak of ‘content’) work alongside the challenges they face as non-native speakers of English and grasping the academic culture viewpoint from which I work. Facing those challenges are very relevant and necessary for them because they either wish to study in English or studying in a western academic context or both and the western academic ‘ethos’ is dominant in the world they live in. And of course, the other ‘world’ they live in is the one that Siemens (2005) and Downes (2005) in which Web 2.0 has given them new access to different forms of communication and ways of forming knowledge. The sociotechnical context for learning and education has changed and is now developing at such a rate due to the internet and other emerging technologies, that a new concept of learning and new approaches to teaching and learning are required. For the EAP practitioner, this realisation came first in the form of distance learning via email communication with learners. Then the establishment of websites whereby learners could access materials related to a specific course, and now followed by tools for synchronous and asynchronous video communication, VLE, LMS and by open online courses (MOOCs). I had equated MOOCs much more with constructivist theory (where the learner actively ‘constructs’ meaning from their interactions with others within an environment in which knowledge and learning is exchanged) after first learning about connectivism as a concept, which I felt lacked rigour. But I see now more clearly its influence in MOOCs I have studied on and I can see its potential by applying each aspect of the theory (from background to foreground) to my own areas of practice.

The three background concepts that have most influence the development of connectivism are:

chaos - knowledge is no longer acquired in a linear manner

complexity and self-organization - chaos complicates pattern recognition and makes it necessary for the learner to self-organise

the existence of networks - that the learning can form and tap into

With knowledge located in dissipated sources and organised chaotically, the learner’s role is to find and recognize hidden patterns, and to make sense of the seeming chaos.

Likewise, English and the ensuing academic culture that is partly language bound can appear incomprehensible to speakers of other languages and those from a different academic background and tradition. Different sources, including faculty members will say conflicting things or what they say may be interpreted differently and because language and conventions evolve, which is impossible to predict a connectivism approach can help to understand the Foreign language and western ‘system’ of education. Perceiving language as a network of networks (e.g. how morphology relates to the syntactic, lexical, and phonological networks etc). In EAP, there is a need to connect the concept of plagiarism, with citing and referencing and with the concept of academic honesty in research and knowledge sharing. They need to navigate the array of internet sources of research findings and the importance of networks is nowadays highly emphasised when it comes to conducting their own research. For language learners, networks are a means of practicing skills such as writing and speaking through the ties they form online. There are many networks that provide answers to queries about language use and meaning.

For language learners, Veselá (2013, p7) writes how language content can be divided according to the Siemens’ principles:

- data (e.g. irregular forms of past tense)

- information (meaning and use of these forms)

- knowledge (ability to use these forms in context)

- meaning (past tense in the context of the English tense system and the possibilities of how to express it)

Whether a foreign language or a foreign academic culture, learners need to decode, understand, and connect new nodes of learning with former ones.

Veselá (2013, p8) does a useful take of the definition of connectivism from an ESOL viewpoint (I've added a column for EAP):

|

Connectivist Principles |

ESOL |

EAP |

|

Connectivism is based on the diversity of viewpoints |

In language, the diversity can be seen in meanings of a word, a phrase, or a sentence in various contexts, as well as its variants (regional, social...). |

In academia, criticality is paramount – being able to dissect various viewpoints in arriving at an educated thesis |

|

Learning is a process of creating connections among the nodes or information resources

|

The connecting of nodes and language networks is described above. In foreign language education it is important to use a variety of information resources |

In primary research originality is vital, for that you need to know all that is out there and be up on what’s going on. You need connections for that. |

|

Education may reside in non-human appliances

|

E-learning uses the systems for education that work without human interference. It is necessary to exploit their potential (e.g. multichannel input – sound, picture, motion, feedback etc.). |

Non-human appliances enable the researcher to collate, organise and cross-reference all existing data in ways undreamt of just decades ago. |

|

Capacity of potential knowledge is more important than the amount of the actual knowledge |

Learning a foreign language is a field in which we can never say that we have learnt it. |

Researchers are forever meant to be pushing the boundaries of knowledge through their own practice as researchers, whilst continually challenging what’s seen as existing knowledge |

|

Maintenance of connections is important for continuous learning |

Our ability requires continual practice. One must add new nodes and connections, also maintain and update old ones. |

As soon as a researcher is out of contact with current streams of research in their field, they become isolated and their own work loses currency |

|

The ability to see connections is the basic skill

|

Mastery of a foreign language is about fluency in the connections in the language networks. |

Very often researchers’ conclusions and claims fall short of the benchmarks of accuracy, reliability and validity, replicability etc |

|

Currency and accuracy are the aim of connectivist activities |

It is necessary to use the sources of the language in current use. |

Seminal work apart, research is advancing so quickly, currency must be proven against the benchmark of the most up to date and authoritative sources |

|

Decision making process is a part of learning |

The possibility to choose is an important factor of the foreign language education. The motivation increases when the learner decides not only about the language, he/she will learn, but also about the field in the case of learning a foreign language for specific purposes |

An example is that often my students’ first choice is Wikipedia, despite all the encouragement we give them to choose other sources (through studies show Wikipedia is a reliable source it is not authoritative). |

So despite my early skepticism, having studied on MOOCs for a few years now, I can see how the principals of connectivism are both reflected in MOOCs I’ve studied on and can provide the basis of effective learning. When thinking about our use of technology in education we can use its principles to guide and evaluate the tasks and activities we use.

References

George Siemens – Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age, Journal of Instructional Technology: https://www.itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.ht

Downes, S. (2005). An introduction to connective knowledge [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.downes.ca/cgi-bin/page.cgi?post=33034.

Downes, S. (2005, December 22). An introduction to connective knowledge [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.downes.ca/cgi-bin/page.cgi?post=33034.

Connectivism has been disseminated through a book (George Siemens, 2006b), a series of articles (Downes, 2005, 2006a, 2006b, 2007a, 2008; Siemens, 2004, 2005, 2006a), blog posts at http://halfanhour.blogspot.com/ and http://www.connectivism.ca/, a large number of presentations at conferences and workshops (see http://www.elearnspace.org/presentations.htm and http://www.downes.ca/me/presentations.htm), and through two instances of multiple open online courses (MOOCs) titled Connectivism and Connective Knowledge, held in 2008 (CCK08 http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/2008/10/30/connectivism-course-cck08/) and 2009 (CCK09 http://ltc.umanitoba.ca/connectivism/?p=198).

Strange week, what with the school inspectors coming from Nursultan and international staff still speculating on their futures in the face of your typical post-Soviet need limit even the most basic information to those at the base of the hierarchy, even if it shoots you in your own foot. This was the week when suddenly local teachers (just to appear to be following policy) wanted in on my classes, even though I had been shouting and screaming for team teaching all year to no avail.

This week we were asked to read Nichols' (2003), A theory for eLearning, and review his 10 eLearning hypotheses.

It was really interesting reading because it puts the reader in the position of looking back at how much eLearning has developed since those times, whilst at the same time, in many instances, showing us how far we can potentially go, as in some ways, not much has changed. At the same time, Nichols provides a retrospective on the two decades prior to its writing, with references as far back as the early eighties, when distance learning and more dislocated and email contact with your tutor were such an innovative break from learning only in the four walls of colleges and universities. We can see how focussed theorists were in those days by how staunchly most of the hypotheses have weathered time since then. For example, the major terms and concepts (pg 2-3) of Online learning; eLearning; Mixed-mode/blended/resource-based learning; Web-based, Web-distributed or Webcapable and Learning Management System (LMS).

Hypothesis 1: eLearning is a means of implementing education that can be applied within varying education models (for example, face to face or distance education) and educational philosophies (for example behaviourism and constructivism).

Hypothesis 2: eLearning enables unique forms of education that fits within the existing paradigms of face to face and distance education.

Hypothesis 3: The choice of eLearning tools should reflect rather than determine the pedagogy of a course; how technology is used is more important than which technology is used.

Hypothesis 4: eLearning advances primarily through the successful implementation of pedagogical innovation.

Hypothesis 5: eLearning can be used in two major ways; the presentation of educational content, and the facilitation of education processes.

Hypothesis 6: eLearning tools are best made to operate within a carefully selected and optimally integrated course design model.

Hypothesis 7: eLearning tools and techniques should be used only after consideration has been given to online vs offline trade-offs.

Hypothesis 8: Effective eLearning practice considers the ways in which end-users will engage with the learning opportunities provided to them.

Hypothesis 9: The overall aim of education, that is, the development of the learner in the context of a predetermined curriculum or set of learning objectives, does not change when eLearning is applied.

Hypothesis 10: Only pedagogical advantages will provide a lasting rationale for implementing eLearning approaches.

I fully agree with most of the hypotheses, mainly because I have used eLearning to achieve teaching/learning goals quite extensively and so I have experience of the basic hypotheses - that is is a method rather than an approach in itself and can fit with different approaches - online and face-to-face or 'situated'. In course H880, we learned in theory and in practice how pedagogy should determine its use, not technology determining the pedagogy. So, hypothesis 4, that ‘eLearning advances primarily through the successful implementation of pedagogical innovation’ resonates with me because pedagogical innovation is far more interesting to me that technology as, for one, in my teaching context, technological innovation is limited by institutional (e.g. restrictions on the use of phones in the classroom - unlike in some university contexts in which I've worked) and there are fewer opportunities and resources to use technology (again, unlike in some university contexts in which I've worked). Therefore, I get more out of developing my approaches to teaching and I find it more interesting anyway as for me, it is the essence of the teaching role - not promoting the latest app or hardware, which might be eye-catching and engaging at first, but whose novelty soon wears off.

I may take some issue with the 'absolutist' terms in which eLearning is referred to in hypotheses 6 and 9, where a course comprises a pre-selected format and content (I guess that could be argued to be a top-down approach, using a traditional course design method). Though I am not sure whether the model has ever been ever successfully applied and adopted longterm by any institution, connectivism (e.g. Siemens, 2005 and Downs, 2005) is a more bottom-up approach, with learning more tailored to the individual's personal learning network (PLN). It constitutes a completely different proposition in terms of course 'design' and of course, it did not emerge until 2 years after the writing of the Nichols (2003) article. As well as reading the articles below, the reader can learn more about connectivism by studying the section on this learning theory from the FutureLearn course, Learning in the Network Age.

References

Downes, S. (2006). Learning networks and connective knowledge. Collective intelligence and elearning, 20, 1-26. Chicago

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. ASTD Learning News, 10(1). Chicago

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Chicago

This blog might contain posts that are only visible to logged-in users, or where only logged-in users can comment. If you have an account on the system, please log in for full access.