I'd been hoping to get over the pennines for an 'A225-visit' to Manchester and finally got the chance for a whistle-stop tour early in 2026.

First location was Manchester Art Gallery which holds one of two copies of Ford Madox Brown's 'Work', which graces the cover of 'Confidence and Crisis'. I've loved this painting for years and I see a little more every time. There are some good resources about it on the Manchester Gallery website.

What was really exciting this time though was to see a relatively recently acquired companion piece - 'Woman's Work - a medley' by Florence Claxton. Whilst Florence may not have known about Ford's painting they sit fantastically together. Claxton satirises the restricted working opportunities for women in a whole variety of ways (in Ford Madox Brown's painting women are at most able to give out some temperance leaflets or get hauled away by the police for selling fruit.)

The detail in Florence Claxton's painting is again fascinating - above the male 'false idol' reclining on his throne you can read 'The proper study of womankind is ...man' 😂

Next stop, Manchester Free Trade Hall. (If anyone wants a flashback to A113 and the sixties - it will be sixty years ago exactly in May since the famous cry of 'Judas' rang out there as the crowd reacted to Bob Dylan's abandonment of acoustic performance!) This was built in the mid-1850s to commemorate the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846.

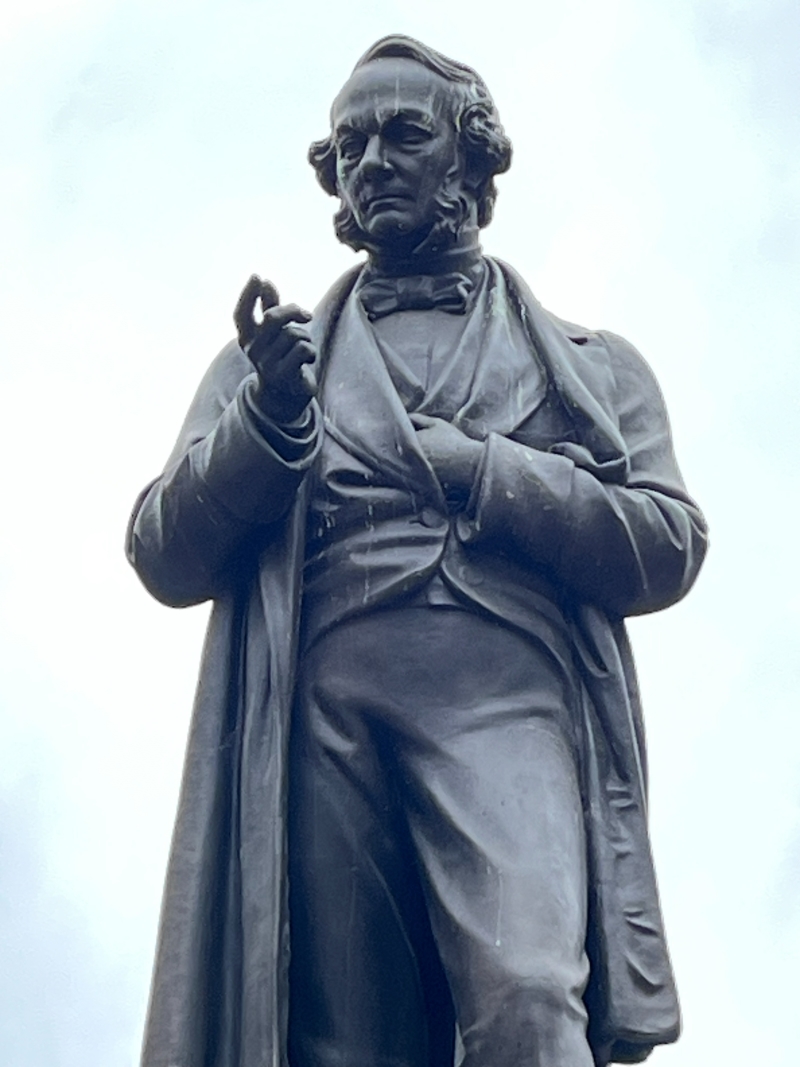

Land for the building was given by cotton manufacturer Richard Cobden, who was elected an MP with the support of the Anti-Corn Law League.

There's iconography across the building celebrating the advantages of 'free trade' and you can see the Anti-Corn Law League symbol of wheat sheafs in the detail below.

The building stands on what was once St Peter's Field, the location of 'Peterloo' - there is a commemorative plaque to mark this and just around the corner, in front of the Convention centre, is a specific memorial that was completed in 2019 for the two hundredth anniversary...

The symbolism on the Peterloo Memorial is again rich, detailed and political. There are images of tools and weaving paraphernalia, linked hands and a compass indicating the direction and distance of other public protests that were met with state violence: Blood Sunday in Northern Ireland, Tiananmen Square, Jallianwala Bagh/Amritsar... The steps commemorate individuals who died at Peterloo and the communities that participated.

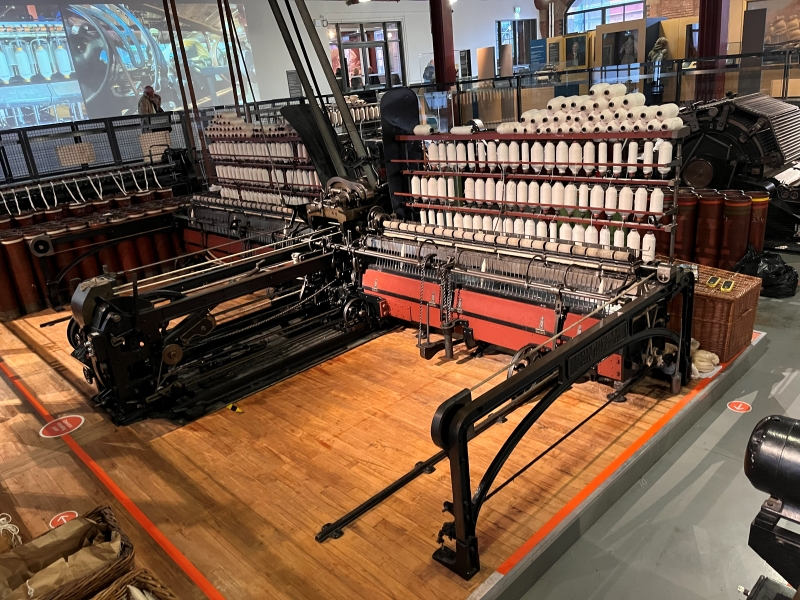

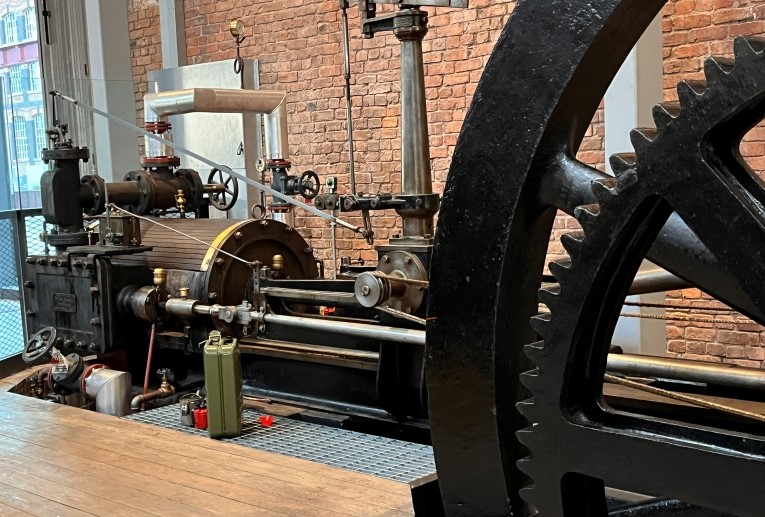

By lunch I'd made it to the Science and Industry Museum - the machinery was surrounded by screaming children, but now on trips from schools that equivalent 19th century Mancunian youth couldn't have imagined, and the screams were (as far as I could tell) of laughter...

Next on my itinerary was the People's History Museum, which is an A225 'must-see' if you're in Manchester.

There's just so much packed into a couple of galleries - and thanks to the OU and A225 - I found so much of it had interest and meaning. The following are just a few snaps of the material that was there.

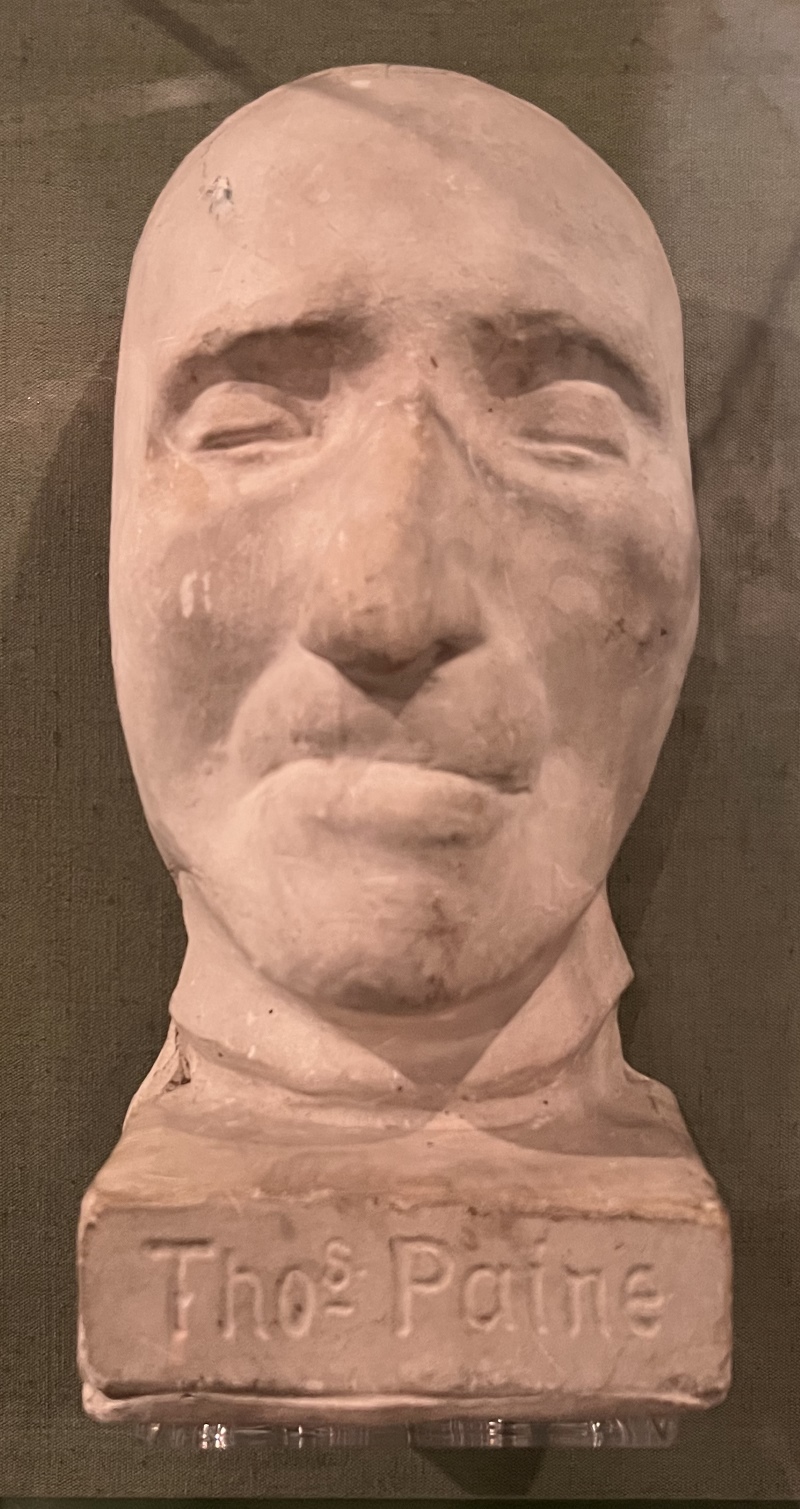

Tom Paine's death mask and the table on which he wrote 'Rights of Man'...

Ceramic commemoration of Peterloo, with reference to the radical journal 'Black Dwarf' and 'Orator Hunt'...

Tin Plate Workers Society banner, from 1821. The museum has a fantastic array of flags and banners from groups and protests across the last two hundred years. This is their oldest union banner - I found it interesting to think what message they wanted to give by prominently including the Union Flag, perhaps that their aims were aligned with the 'true' national interest?

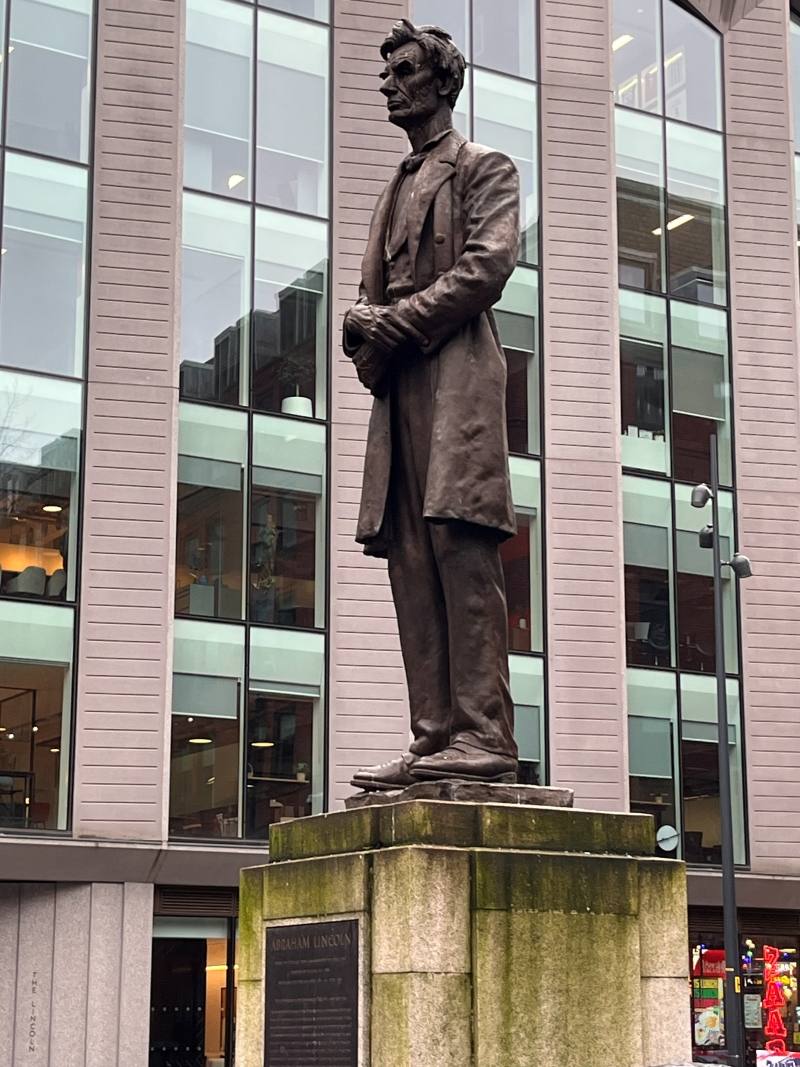

Outside again for perhaps a surprising figure - 'Honest Abe' stands tall in Lincoln Square. Originally destined for Parliament Square this statue ended up in Manchester when an alternative version was prefered for the London site. Local Manchester authorities argued that it should celebrate the response (welcomed by Lincoln at the time) of Lancashire textile workers to the 'Cotton Famine' in the 1860s.

We may study the past, but we live in the present.

Lincoln Square is the location for a 'camp' of homeless people, apparently 'migrants' who have been moved around a number of public spaces in Manchester in recent years.

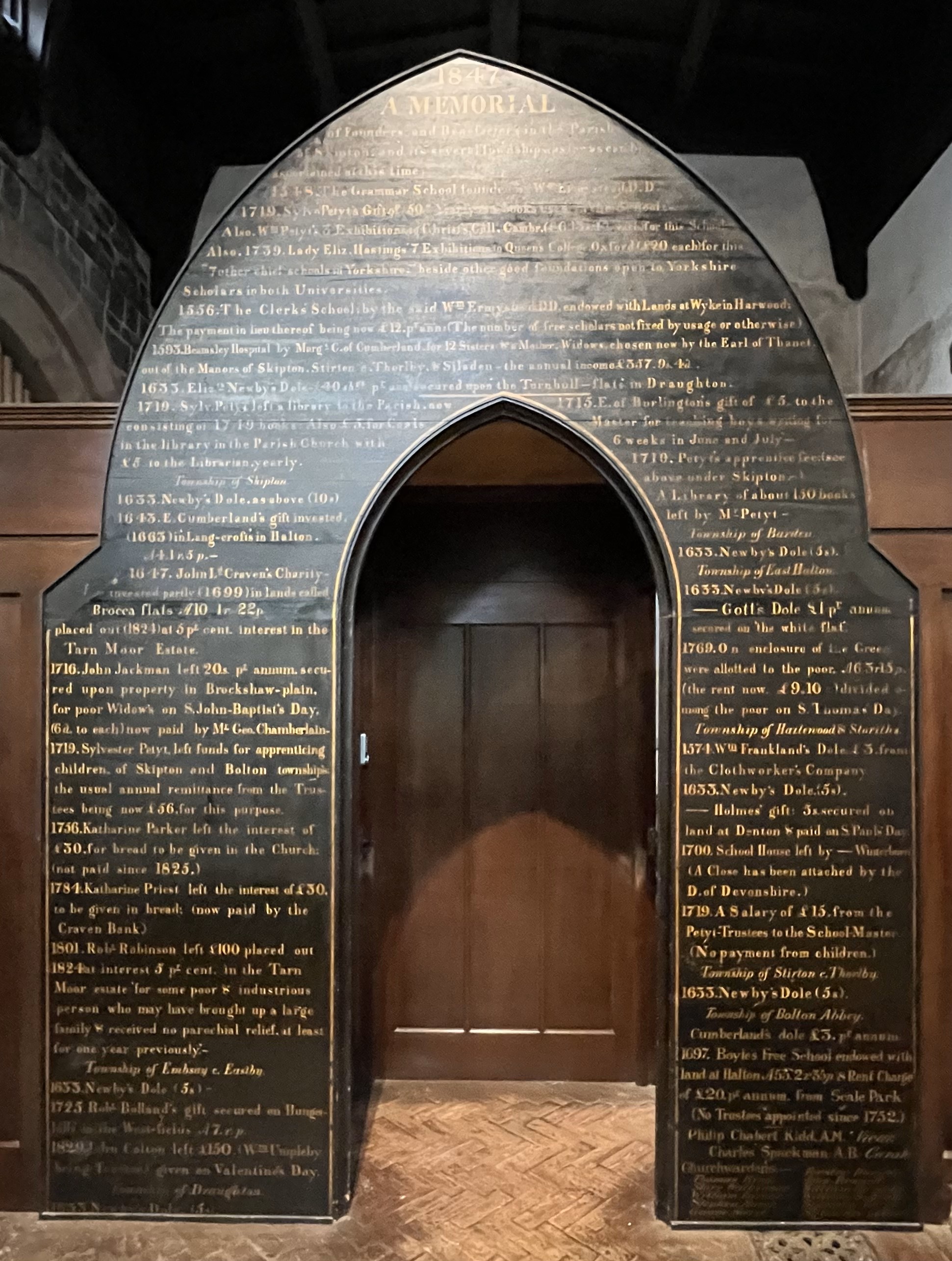

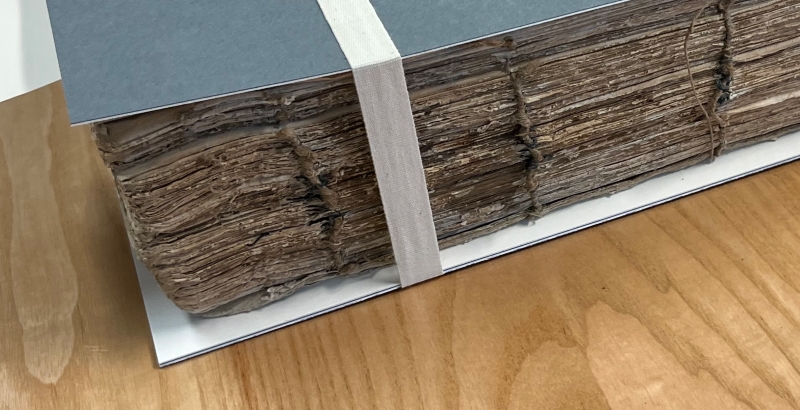

My final stopping place was Chethams Library (it's Cheethams - I of course guessed it wrong first time 😂) Originally a religious house, it was acquired by a very wealthy Manchester merchant, Humphrey Chetham, in the 17th century - whose will established a school and library in 1653.

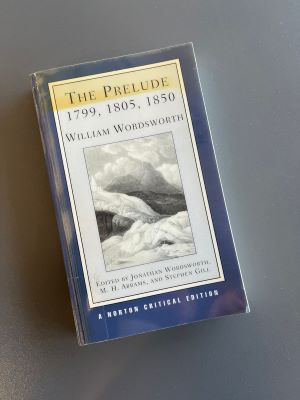

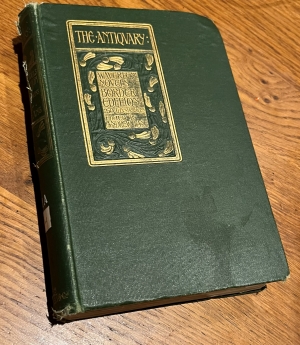

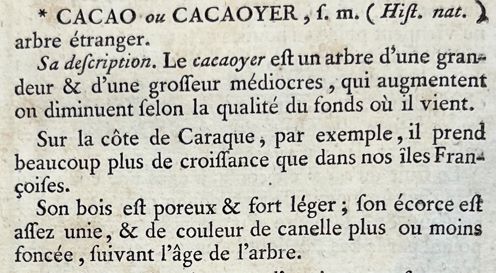

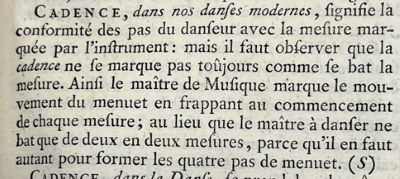

This was a lovely place to think back on A223 and the growth and influence of the printed word across society.

Humphrey Chetham also funded a number of chained libraries for local parish churches - stocked with Godly reading for local congregations (interesting to think who could have actually accessed these).

But it wasn't all A223 - there's one fabulous link to A225 in this little alcove...

In 1845 this was the regular meeting and study space for .... Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Outside the 'Hungry Forties' were biting hard in Manchester, here they would chiefly read economics texts from the library and discuss ideas that became the basis for the Communist Manifesto written a couple of years later.

Have to say it was an exhausting day - but great fun. Of course Manchester was also a key site in the Women's Suffrage movement, so perhaps I might try and get back for a visit to the Pankhurst Museum watch this space! 😀

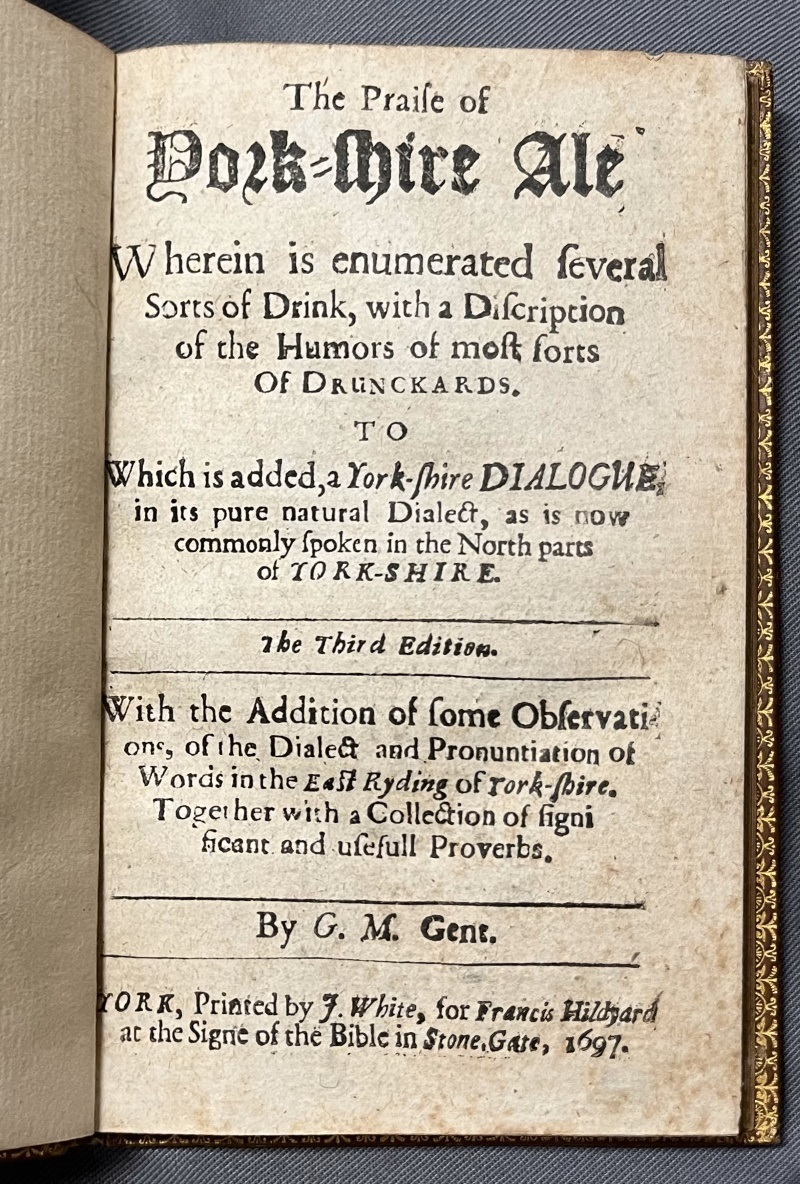

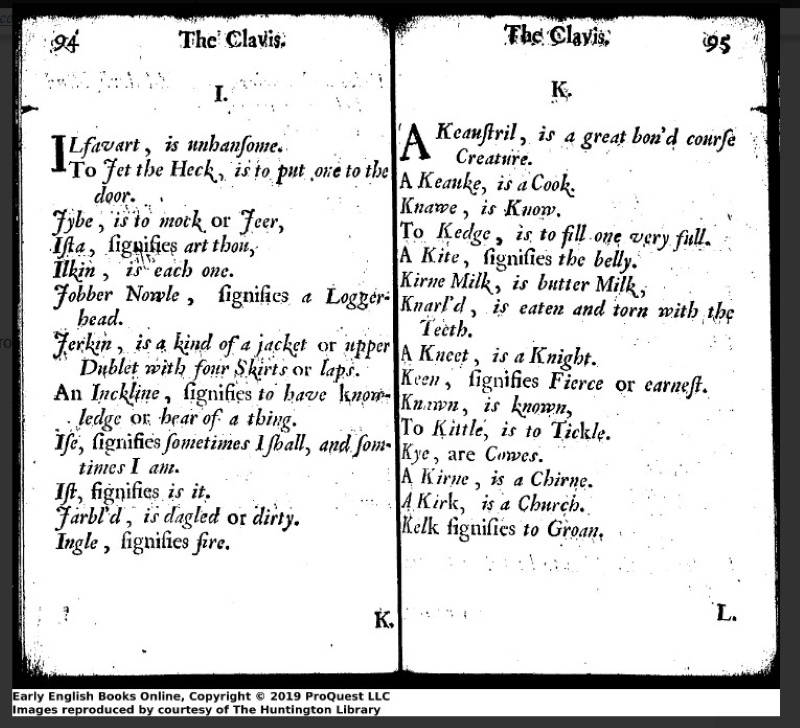

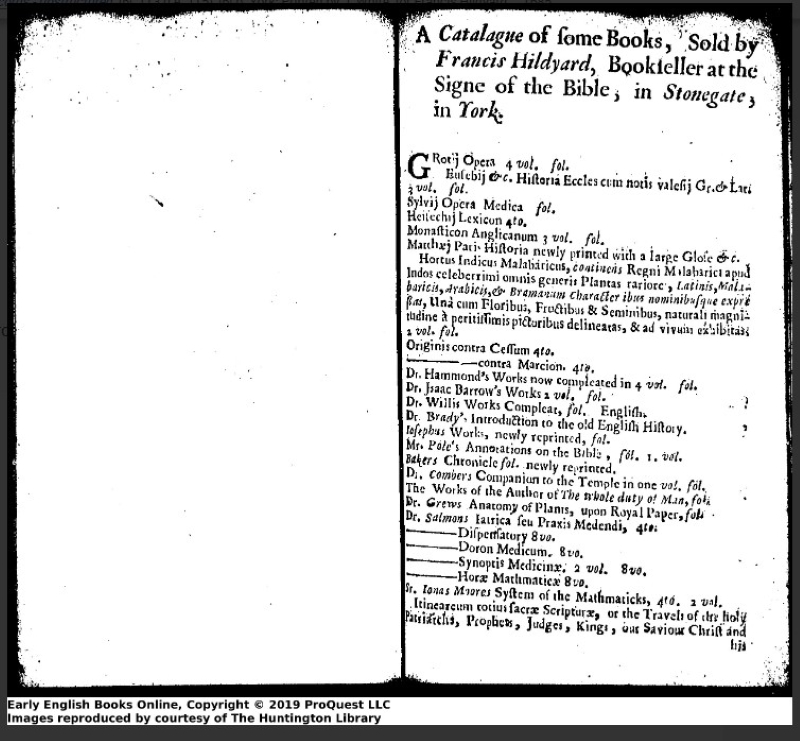

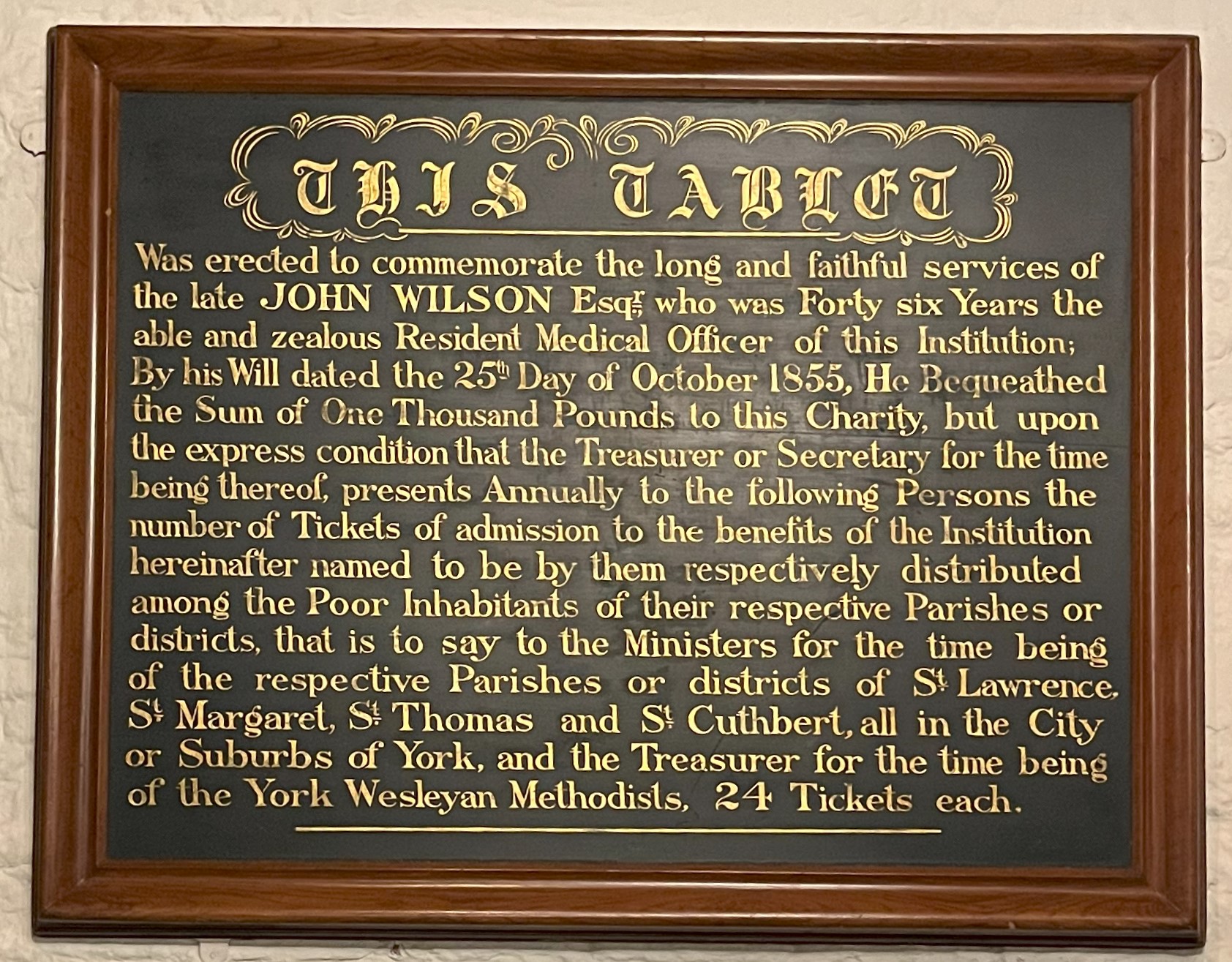

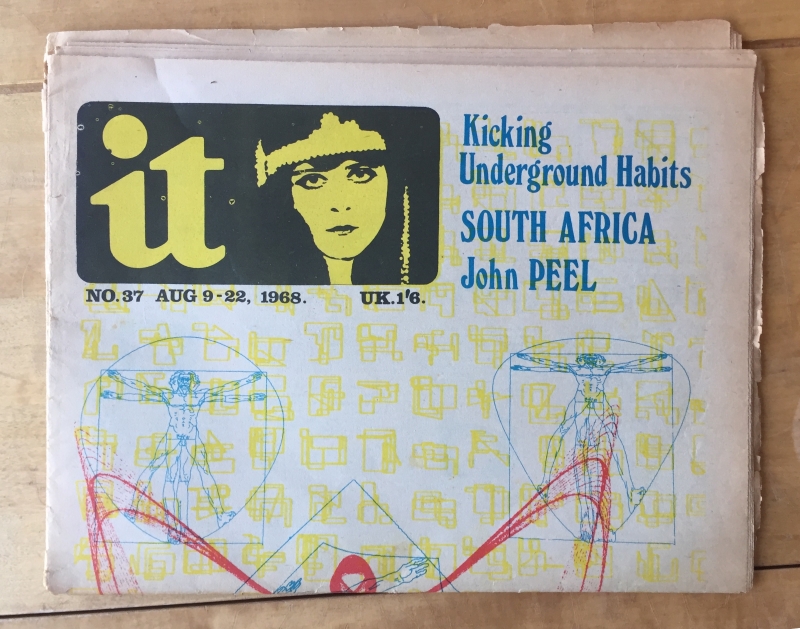

In folklore, 'printer's devils' caused mischief by misspelling words and inverting and removing type. It became a nickname for printers' assistants, who might also make mistakes! This little devil has only been perched here in the centre of York since 1888, but marks the entrance to an alley that served a print workshop active in the early modern period.

In folklore, 'printer's devils' caused mischief by misspelling words and inverting and removing type. It became a nickname for printers' assistants, who might also make mistakes! This little devil has only been perched here in the centre of York since 1888, but marks the entrance to an alley that served a print workshop active in the early modern period.