I have just read this report (OER Research Hub evidence report) about the impact of OER and I found it a really interesting read for a couple of reasons. Firstly, the idea of openness in education appeals to me per se, it plays right into my two main beliefs about what a good (higher) education provision should do:

1. It should be accessible to as many people as possible

2. It should be built on sharing best practice

Secondly, because I felt that so much of the report could be applied to innovative practice in education in general, irrespective of their openness. For example, I am just in the final throes of writing a report about lecture capture use at King's College London. In it the data from students shows that they strongly believe the use of lecture capture improves their performance - staff do not feel any where near as strongly. And where the educators do see an effect , they often pick up on the complicated factors that may mediate the relationship. This is similar to the pattern found for OER where only 27.5% of educators believe that OER use results in better test scores for students in contrast to 31.9% of students believing this and educators identify a range of mediators. Why is this similarity important you might ask? Well I think it is important because OER has coverage, it has a research base and lots of practice within higher education is still lacking a solid evidence base so the fact there may be similarities could allow us to extrapolate findings from OER to other initiatives but it can also serve as a template to develop an evidence base for the other areas where it is lacking.

Other than this big picture on providing a research base for educational practice, the aim of reading this report was to identified key issues in OER so back to the business in hand:

Issue 1: Getting educators creating

The report showed that 67.5% of educators viewed open licensing as important and over 55% were familiar with creative commons and yet less than 13% (so less than a quarter of those with the licensing knowledge) had ever published anything in this way. Now of course you do not need every single teacher writing their own material and publishing - this somewhat goes against some of the tenets of open education (and certainly learning objects which impacted on the OER movement significantly) but this small percentage seems insufficient to sustain a high quality dynamic provision. I can completely understand why this is so low - later in the report there is comment on how OER does not seem to have related in policy change and certainly I can see having produced OER will do me no favours when it comes to managing my workload or getting promoted. For me the next big thing to investigate to address this issue is asking the question: What are the barriers to producing open education resources for educators and can these be removed?

Issue 2: Getting parity in indicators

The report also identified the different indicators that educators and learners used in selecting their OER. I was pleasantly surprised to see that both cohorts felt a clear description of learning outcomes was important but I was less surprised to see quite different ratings for the provenance of the material - a reputable source was much more important to educators than learners. For anyone who has ever marked an essay citing wikipedia you may be able to see where I am going with this - we need to all be sharing the same ideas of what is acceptable and suitable - if not, neither educator or learners will be fully satisfied with the education provision. Arguably educators are best placed to guide learners in this but unless we articulate what we think a learner should consider - a set of standards if you like, how can we expect them to realise this is important in a world where nearly everyone can claim to be an expert on something. So this brings me to condoms. I don't remember much about sex education from school but I do remember the catchy statement 'If it is doesn't have a kite, don't fly it', referring of course to the kite-mark for the British Standards Institution. I am not sure how you would rubber stamp a set of OER (no pun intended) and certainly it would not be possible to use the same BSI tests for condoms (more thorough than you may think - watch the video). I also don't think you would necessarily want something across the board akin to amazon customer reviews but I do think educators encouraging use of OER for a specific programme of study or activity might provide a checklist of things to look out for, explaining why each is important.

Issue 3: Sustainable financing

Something that has always worried me about OER is how they can be sustainable when produced on a mass scale like OpenLearn and MOOCs via FutureLearn. As someone who was based at the OU and worked on a number of module productions, we were put under a certain amount of pressure to create resources for OpenLearn alongside module production - this was not too hard because there was nearly always something that could be easily adapted and we were told it was a recruitment tool. But this report indicates it is not that great a tool. So longer term it may become unsustainable to keep producing OER unless there is another way to bring money in. One topical suggestion might be to sell off learner data facebook-style but, in all seriousness, I think this raises another issue for further research - what properties of OER are more likely to bridge into formal paid for learning and how can we ensure a proportion of OER provision does this to sustain the entire provision.

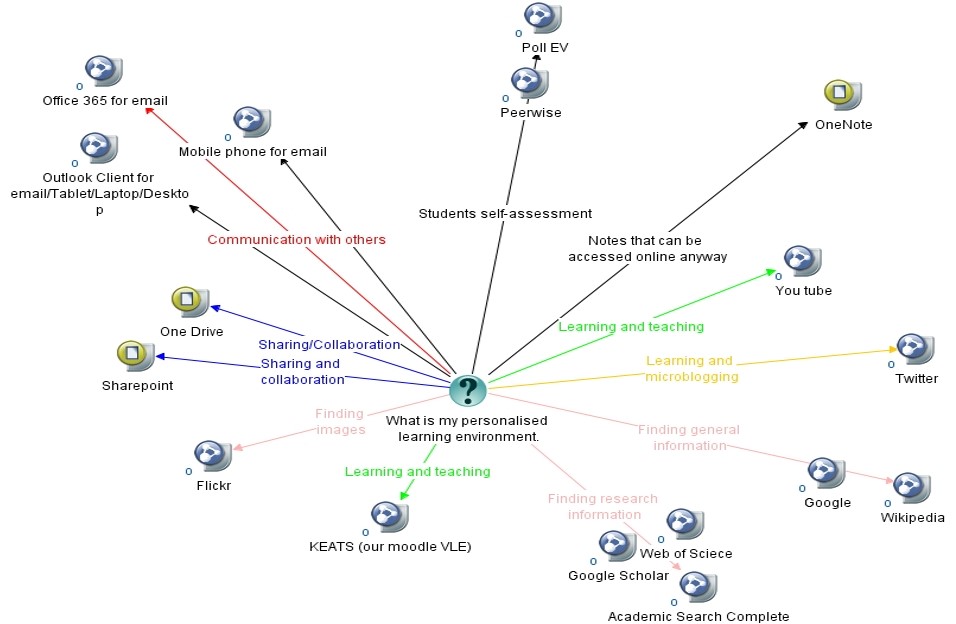

Seeing this map made me realise that I use far more tools than those provided by the VLE. Even if I look only at those used for study of H800 a reasonable proportion would still be listed. So now that I have found my PLE, what do I really think it means.

Seeing this map made me realise that I use far more tools than those provided by the VLE. Even if I look only at those used for study of H800 a reasonable proportion would still be listed. So now that I have found my PLE, what do I really think it means.