This post is for Ven, John, Michael and Gill.

Some of my students, fellow students and colleagues have been recently bereaved, and as they go through that experience which we all have to suffer - but for which none of us can prepare, I wanted to offer my sympathy, or more properly - my empathy.

I lost my mum about a year ago. It was very sudden, although she had been frail for a while. I did not expect the phone call when it came to say she had had a stroke. I wasn't sure what to do, didn't know how serious that was. People do recover from strokes, right?

It was the busiest time of my working year. I emailed vaguely to my managers, not sure what to do about my hefty workload. Fortunately one of them, realising better than I did how serious the situation was, immediately offered to provide cover for my students. I then also asked this of my other managers. I only took two weeks. I realise now I should have taken much longer and done more to get time away during a period when I needed to be with family and friends, and when I found it difficult and painful to focus on work.

In today's world we are often managing ourselves and may feel great responsibility to those we work for and with. Perhaps for the lost person's sake, we want to continue to be a good colleague, a supportive teacher, a diligent student.

Camus's novel LÉtranger - The Stranger begins with the protagonist asking for the day off to go to his mother's funeral. His boss looks strangely at him and he assumes this is because he wants time off work, but in fact it's because his boss finds it hard to understand how he can be so factual and unemotional in his request. I feel as if nowadays we have all become strangers to emotion in the workplace, so much so that we have to try to provide special resources to support anxiety, stress and depression rather than look to see if these are created by the way in which our normal emotions are not supported at work and in other areas of our lives.

The psychologist Freud suggested that if grief is not appropriately felt and expressed, then mourning becomes melancholia. We can become stuck, start to behave in odd ways in order not to let go the person we have lost. We need time to experience the overwhelming emotions of loss in bereavement, to come to terms with the sudden huge gap where someone once lived alongside us.

It may be that time at work or in study is a welcome opportunity to engage with people who are supportive of our grief. For myself, although I tried to struggle on for a while, I deferred from my own studies. I couldn't sit still and concentrate on abstract ideas. Once I realised that I had not given myself sufficient space at the time I lost my mum, I began taking sporadic time out of work whenever I could. As it comes up to the anniversary of losing mum, I am mindful to look out for time for her and my own feelings.

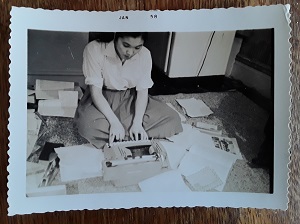

Painful and difficult tasks had to be tackled after mum's death: sorting through books and papers, closing her Facebook page so 'birthday' reminders didn't pop up for her grandchildren (the page can be left as a memorial page), listing with my Dad their belongings to agree how these might be eventually shared with my brother and sister, choosing some jewellery and other items for her grandchildren.

As I went through mum's books, I found a familiar set of gardening books by writers whose gardens we had visited together: Vita Sackville-West, Beth Chatto, Margery Fish. I had a patch of boring lawn in front of my house which I had always intended to dig out for a flower garden. I began to do this, on bad days throwing myself into the task in the mud and rain. I bought flowering plants which I put in, along the philosophy of figuring it out as I went along, as 'all plants look pretty'. They didn't. Some flowers I had bought in an access of grief were in colours that clashed with themselves - quite an achievement for a plant.

On a second trip to sort out more of mum's possessions, I found some books about decorative vegetable gardening by Joy Larkcom, a writer whom mum had become close friends with after translating Japanese seed packets for her books on oriental vegetables. I had always wanted to grow vegetables at the front of my house but felt my neighbours might object to ugly rows of cabbages. (They once complained because I hadn't mowed the lawn! OK, I hadn't mowed the lawn for about four months and it was a bit messy). Decorative vegetable gardening seemed perfect. I knew my mum would have loved the idea and even my neighbours might like it. (They say now: "It's messy - but arty.")

On the left, the ugly flower garden. On the right, the 'potager' - mixture of vegetables and edible flowers.

I post pictures on Instagram of my #PotagerProgress, sharing with friends and the world. I'm often reminded of mum, as I feel my chapped hands (mum's hands at the height of her gardening days were also rough with digging), or put in a plant she would have liked to hear about, or find some disgusting pest she would have sympathised about. Sometimes I still burst into tears as I grub about putting in seeds, and that's OK - nobody even knows (my secret is safe with you, right?). Gardening is a forgiving activity. If you get it wrong and the seedlings shrivel up - they are just plants, you learn from your mistake. If you bought plants that even clash with themselves you can throw them out. (No, of course I didn't! I'm still trying to find places in the garden for the awkward ugly plants. There are lots of plants people will throw away after a year, even though they're perennials, but I'm unable to dig out my own violas and throw them away and have surreptitiously picked up plants other people have thrown out.) There can also be happy accidents - that lovely bank of white flowers in my garden are some salad rocket that bolted; the flowers are edible too - they have a delicious sweet yet peppery taste.

This white viola is 'leggy' in its second year - seen as a fault if it's meant to be a clump in a flower bed. On the right are two 'rescue pelargoniums' I found thrown out on a path last autumn.

Sometimes as I garden, I think 'mum would not have done it like this', and feel anxious that I'm not honouring her memory properly. Actually, mum changed her ways as she went on in life. Remembering her is a process that is part of my changeable life, not something which preserves the things she did and loved as if under glass.

You never get over losing someone so close. However Freud suggested that if we move through mourning appropriately, it's as if the person we lost becomes a part of us. We get that great gift of recognising them in ourselves, and can move on in life celebrating their memory rather than clinging to something material which has gone. Rather than get over it, we recover - lay sympathy, love and acceptance over grief so that it softens and the pain is no longer unbearably sharp.For this, though, we need to allow ourselves time and space in which to mourn, to remember, to regret. We mustn't be a Stranger to the intense emotions of rage and sadness which do seem as if they may overwhelm us at times. These too will pass, but not if we try to block them and push them back. Only if we allow them free passage, and ourselves what time we need for recovery.

(My Instagram account: https://www.instagram.com/rhiwbinapotager/?hl=en)