Ironically, the strike action I'm taking against neo-liberal management of education impacts on a module I teach that critiques the neo-liberal approach to education (EE814: Addressing inequality and difference in educational practice.)

A concept which we encourage students to define and use on this module is 'discourse'. I find this helpful in understanding how management can continue to blithely pursue patently absurd neo-liberal policies in spite of the cries of anguish from those of us who have to try to deliver learning across instead of along these lines.

'Discourse' (drawing on Michel Foucault's work) is the idea that society is set up in certain ways (along lines of power), so only some thinking has legitimate expression. We have to speak up within discourse, but at the same time we are always creating it so it does shift. A dramatic example of shift in discourse is #MeToo and #TimesUp. Women have been protesting the way in which men treat us for centuries - famously in Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman - first published in 1792. We have frequently and infamously been ignored in spite of widespread anger and scorn, vociferously expressed by Second Wave feminist activists highlighting unreasonable excuses blaming women for our own harassment. It's not until a final shift of power in 'discourse' that these protests can get heard and taken seriously. (The earlier work against abusive power in 'discourse' is of course fundamental in building up to that shift.)

As academics, we devoutly hope that our protest against the pensions proposals put to us can prove such a shift against the neo-liberal approach to education (marketisation).

Screenshot of letter to The Times from VC of Cambridge University

We all hope that this shift can take place before the final neo-liberal absurdity of the current Minister for Higher Education's proposal to rank degrees according to how much graduates from them earn. (This is all the more stupid because there is an inbuilt ranking measure in degrees already. How many students graduate from the degree with a good pass mark indicates how much they have learnt and therefore how good a degree it is. Res ipsa loquitur, as Captain Jack Sparrow puts it. NB, Minister - socio-economic deprivation should be considered as a factor in this measure.)

Article by Guardian writer Suzanne Moore.

On EE814, we draw on the writing of Michael Apple (2006a, 2006b - this one is very short, 1990) and a key article by Olssen and Peters (2007) which looks at neo-liberalism in Higher Education. (My DD102 and DD103 students will be interested to hear that Olssen and Peters use the thinking of Hayek and Stiglitz, among others, in their article - two economics thinkers we explore on those modules as well.)

Basically, the neo-liberal approach to education treats education like a marketplace. It argues that the customer is always right and that we should tailor our education provision to demand. If the students want modules on postfeminist needlework, then we should supply those. (Warning - that last link goes to a highly satirical site with material some may find offensive.) Academic teaching staff have been vociferous in condemning the considerable recent emphasis put on student satisfaction surveys. These are likely to reward charismatic individuals rather than rigorous teaching design making students work hard to achieve more highly. I have heard of staff chastised for poor results in a student satisfaction survey, while the same student cohort were walking away with many more First degree grades than their peers on comparable courses.

Secondly, the neo-liberal approach to education assumes that students come to learn in order to move straight into gainful employment. Gainful to the economy that is, not gainful in the sense of being satisfying to them in any spiritual way or contributing to society in other ways than economic. Hence, the assumption by the Minister for Higher Education that measuring degrees by eventual income is a good way to go. I get routinely asked what employability skills students gain on EE814. As this is a postgraduate education module, many of my students are already employed as teachers - the idea that they might want to improve their teaching skills while in post doesn't seem to enter into the neo-liberal equation. (Some of us refuse to answer stupid questions like these about our courses, except by sending back long and dull diatribes about neo-liberalism.)

Thirdly, the neo-liberal management of education seems to need a lot of form-filling and oversight. In all areas of public sector work (police, schools education, NHS) we hear about spending time accounting for the time we would rather be spending doing our work. There is a complete lack of trust of workers in delivering on basic tasks. Nor is there any interest in supporting us as workers. This vast array of performance indicators is not designed to identify training needs or help build our skillbase. Nor have I ever heard of an academic staff member identified as not delivering appropriately and sacked because of performance indicators. Promotions, too, happen in a structure that appears to be outwith these mundane performance measurements. It's not very clear what use they are being put to.

One aspect of marketisation of Higher Education seems to be the trend for expensive and beautiful new buildings. Some are saying that the reason Universities UK want the pension scheme set up on different grounds, is that the way it's currently set up is regarded as a liability by banks who would lend them more money if the pension scheme could be accounted for in a different way. (It seems that bankers have a pretty weird 'discourse' going on too.) But why do universities want all these new buildings? many not suitable for teaching or research purposes? Is it just because buildings as 'stock' add to monetary value and this is seen as the best, most business-like way to manage our colleges and universities?

Although many of Cardiff University's new buildings are for research purposes, they are promoted here in business terms. They include an Innovation Centre: "Providing companies with the resources and support to encourage growth with confidence." Any educational aspect of this project is lost in the account of it.

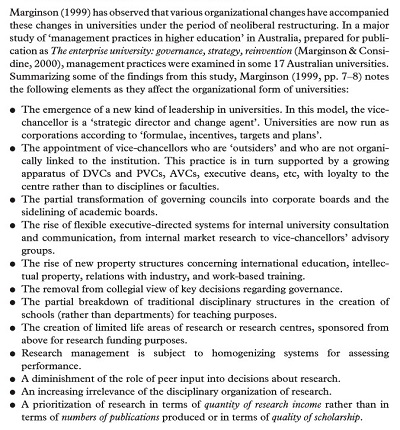

I could go on, but I will just reproduce this page (p.327) from Olssen and Peters which seems particularly pertinent, and let you read the rest of their article yourselves.

References

Apple, M. (1990) Ideology and Curriculum, Hove, Psychology Press

Apple, M.W. (2006a) Educating the ‘Right’ Way: Markets, Standards, God and Inequality, New York, Routledge.Apple, M. (2006b) ‘Understanding and Interpreting Neoliberalism and Neoconservatism in Education’, Pedagogies: an International Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 21–5.

Mark Olssen & Michael A. Peters

(2007)

Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: from the free market to knowledge capitalism,

Journal of Education Policy,

20:3,

313-345,

DOI: 10.1080/02680930500108718