A queer approach to sexual preference labelling in art-history: looking at case studies in British mid-twentieth century art: 2. Keith Vaughan

The aim of this group of blogs is to look critically at some of the publications relating to gay male artists in the mid-twentieth century. This is in part to begin trawling for a dissertation topic for my MA in Art History. My initial thoughts relate to focusing on one of these artists, although their contexts include each other, their treatment of male nudes in relation to the iconographic, contextual and stylistic features which propose such a subject for art (for some of the choices this will include photography as well as painting) and ‘queer theory’. This will look at the issue of labelling of course, particularly at the important terminology of ‘homosexuality’, which dominated the period. My hypothesis will probably be that such a term was, and remains, a means of marginalising, even to the point of negation, of such art. My probable choice of artist at this stage is probably Keith Vaughan, hence this blog is a start in a later reading project.

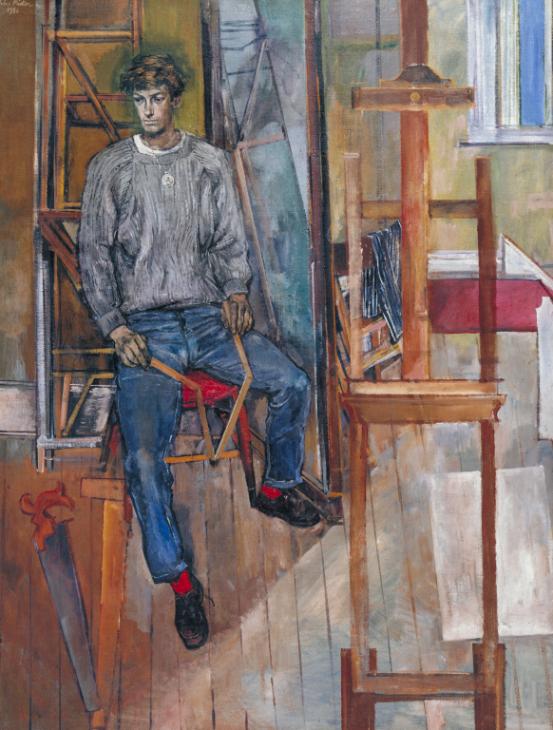

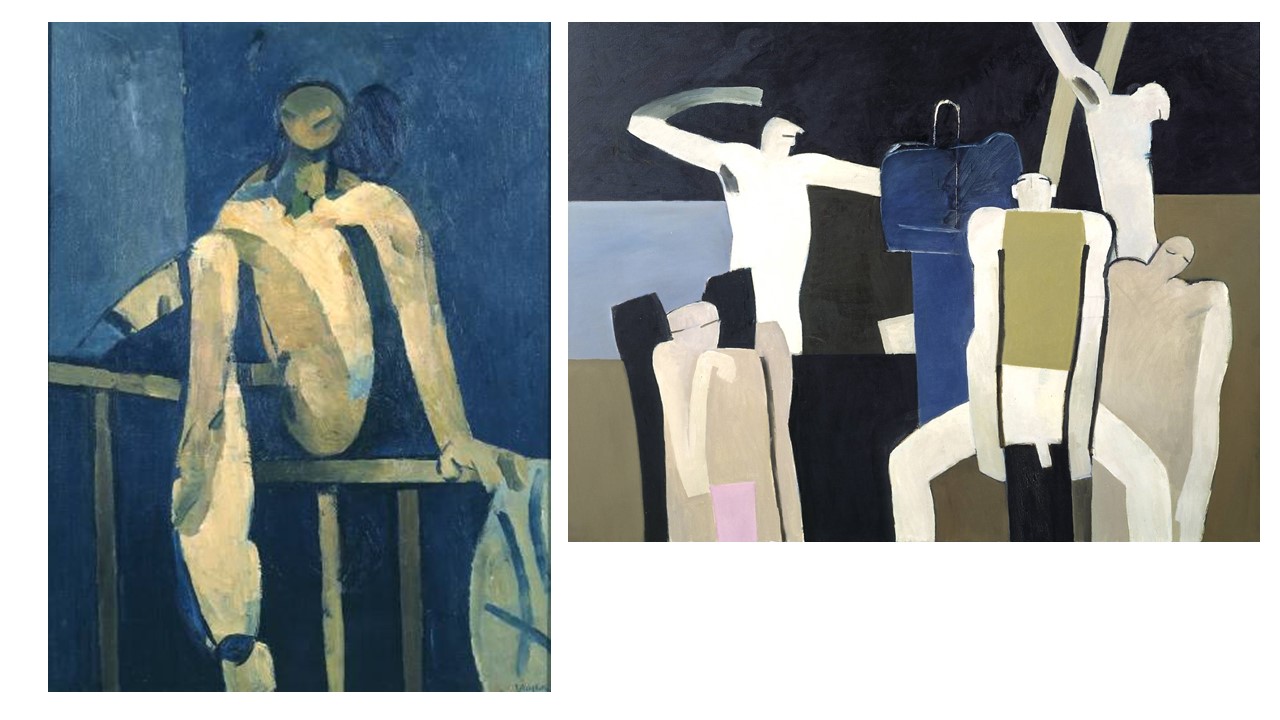

Frances Spalding’s (2005:3) biography of Minton is not a fair basis of comparison with Vaughan and that partly because her biography is apparently aiming for an ‘understanding of homosexuality’. Malcolm Yorke’s (1990) excellent biography of Vaughan makes no such claims and merely charts the artistic, social and sexual life of Vaughan (and the impact upon that life of contemporary constructions of homosexuality, including those which Vaughan intermittently internalised). It is less motivated by attempts to ‘understand’ on the basis of a limited case-study and a belief that the term ‘homosexual’ is ontologically valid. In short, here, the essence of what the ‘homosexual’ might be is neither defined nor imposed as a definition of a part of an assumed reality. Indeed I don’t think the term is validated. In this respect Vaughan’s book makes a much easier step towards a queer reading of mind-twentieth century reception of ‘scientific’ and medicalised discourse on homosexuality. Such a reading needs to explain the methods of his public art as well as his private erotica, such as The Leaping Figure here.

Vaughan himself, like Minton, felt ambivalence about ‘homosexuals’, which he projected as an ambivalence about other gay men (together with an ability to exploit and diminish those he came into sexual or social contact) and introjected as a, in his case, almost virulent self-hatred. Vaughan’s campaigning journals show a tendency to prefer a sexuality which crossed more than normative sexual practice boundaries, exploring the potential of sex as an onanistic science dependent on machines and inanimate objects. When people were involved, he chose even more obviously less powerful personalities as his partners whom he could belittle and hate (although often only privately in his journals as his partner, – as near as he ever got - Ramsay McClure, found to his cost). But he also romanticised and loved these same people in the moment, without any necessary recourse to ever seeing their personhood, often using their marginalised status (and often their poverty as in the case of his young Mexican lover) as the basis of such Romanticism. Eminent amongst these was Johnny Walsh (166f.). And herein lies a conundrum. Unlike Bacon, who seemed to feel no great visible responsibility to working (and criminal and indigent) class – I’m not sure the distinction was ever made in these haute bourgeois English artists – partners such as George Dyer, Vaughan also attempted to become paedagogos (for a time) to Walsh, whom he often characterised as a kouros.

These dynamic relationships of projection of the lesser and introjection of the ideal in the end allowed Vaughan to see himself as unlike other ‘homosexuals (not camp like Isherwood and Minton) but ‘special, unique (47).’

These contradictions do not exemplify, as it was sometimes thought at the time (by E.M. Forster for instance right into a privileged old age) homosexual love, they are (I would argue) distortions caused by the ways in which heteronormative values assumed the qualities of the ‘natural’ ideal of sexual life. Hence the liberation involved in ‘queer theory’ which looks at how that which lies outside the supposed and ideological norm (often practices in real life that are silent or silenced by ideology) survive nevertheless. Looked at from this perspective, Vaughan’s queerness looks very like that that of Picasso – both based on giving primacy of artistic solutions to problems experienced in the human sphere of activity, especially those of sexual love.

Vaughan theorised homosexuality obsessively (even to the extent of a totally forensically objective definition of the material ‘symptoms’ of love as a kind of necessary psychosis (234). I think he was correct to see ‘homosexuality’, as it was defined in the theory of the time as a category tied to constraining and marginalising social roles, the ‘other’ to heteronormativity. What he failed to see (unsurprisingly for the time when his sexual life may have led to long-term imprisonment or chemical castration) was its socially-constructed nature. He lived long enough to despise ‘Gay Lib’ for ‘flaunting itself in the face of the public (cited 254)’ (as if what is public were only heteronormative). He tended to use the distortions of Freudian theory (which he contacted mainly through secondary texts) to see even his own ‘homosexuality’ – if not his sexuality as a whole - as a form of immaturity, one that he had not achieved on the route to heteronormativity: ‘I have regressed even from the immaturity of homosexuality to an almost pre-natal infantilism (cited 237).’

Of course there is much to say here that I want to leave in silence (for now) because its importance for me at the moment is the way in which a queer approach to Vaughan’s art rescues the artist from the time-bound and limited thinker of the journals. That mass of contradictions (the Journals and Vaughan as a biography) matters and helps with the art but does not show his importance. For me this comes from his rethinking of the traditions embodied in the male nude trope – one that Vaughan saw has predictable from his homosexuality (197) but as essentially contributory to a breakthrough in artistic technique (technique he taught at Slade as before (198) in terms of the primacy of painterly composition and pioneered in art in the practice of ‘assembly’ paintings (200) – as in the Ninth Assembly of Figures here, which he saw as classical in form if both classical and romantic in subject. He was devastated when he discovered that the basic invisibility of Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling male nudes (which he thought validated those fusions) could not be ‘seen’ from the chapel floor and therefore could not have (he felt then) created a tradition (230).

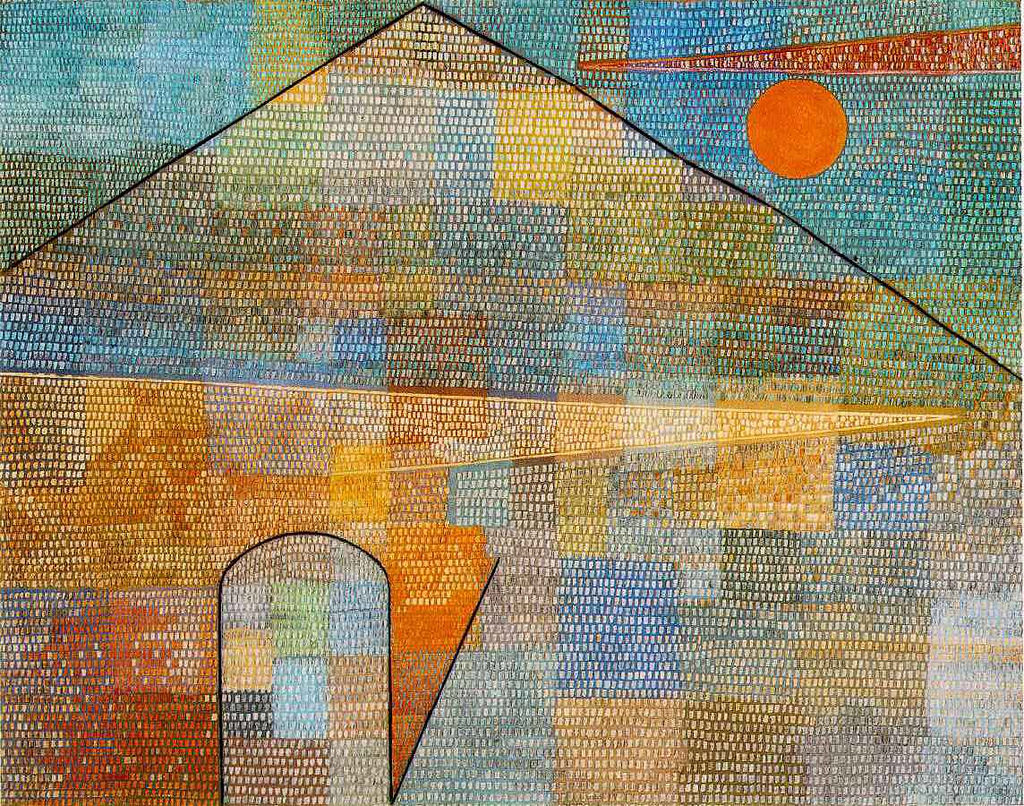

Yet tradition there was – one, though I’m still working on it, I would call a queer tradition that amalgamated various sources that were not equitable with homosexuality nor with any directly intended expression of male desire for ocular evidence of other male bodies (sexual or not): this tradition included the academic tradition of the male nude and the male nude considered as emblematic of idealised proportions of form and style. Both owed something to Winckelmann’s readings of the classical and Renaissance tradition (including Raphael and Michelangelo), to Neo-Classicism and the function of the Academies in Europe (including Britain, in the work of William Etty in the nineteenth-century) which also fed off Winckelmann, although now mixed with its apparent opposite, Goethean romanticism. However, the most formidable model, especially for the reformulation of a notion of what we might mean by the classical nude is Cezanne, Vaughan’s key model for his male nudes in public painting. Yorke (1990:40f) summarises thus how Vaughan felt he honoured the classical forms in Cezanne in his own painting, something with which I fully concur:

Structure was imposed on the teeming chaos of reality by eliminating unnecessary detail, simplifying trees to masses …, suppressing any individuality in bathers’ faces or bodies, and simultaneously making every part of the picture conform to an underlying geometrical structure, distorting forms to this end if necessary. (And more)

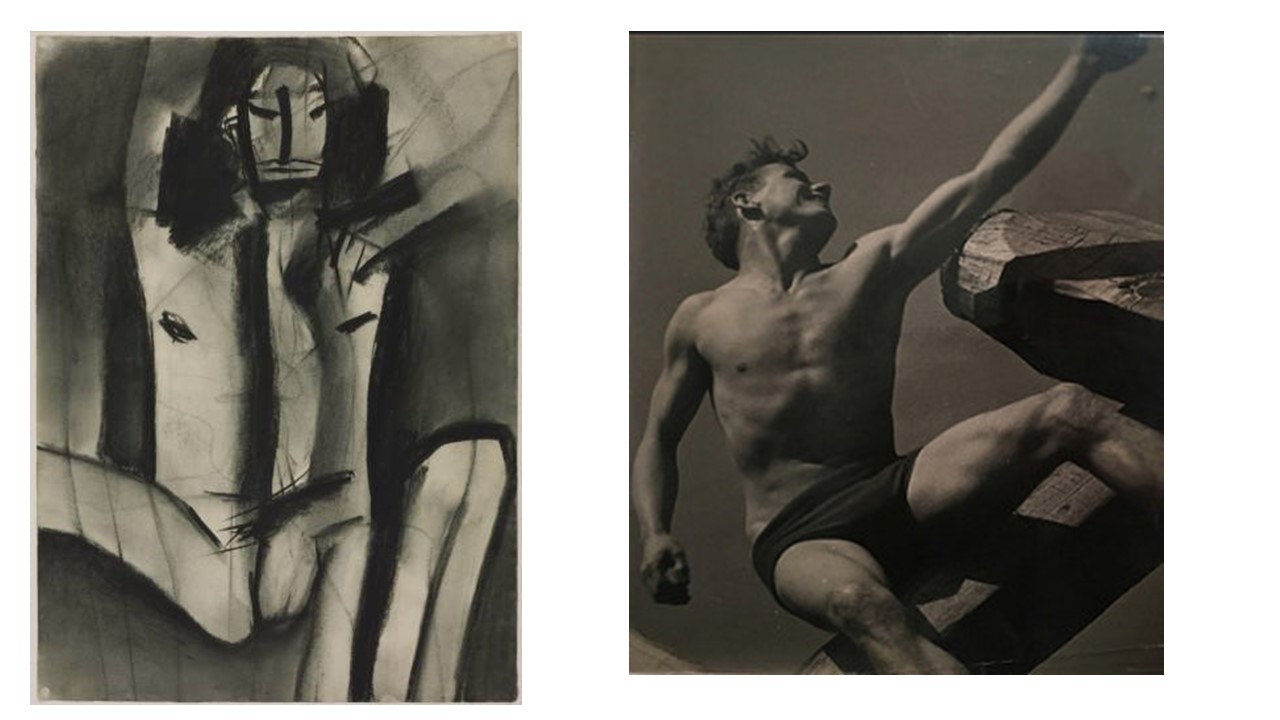

I too hope to say more of Cezanne’s male nudes when I write in earnest, since their reception has historically been mediated through a thick varnish of homophobia which refuses to see desire in them lest it taint an ideal Cezanne. Cezanne did not need to be ‘homosexual’ to reinvent the male nude as both classical form and romantic icon, I’ll argue. Moreover, we need to take this classicising even of the most romantic and desire-imbued forms seriously in Vaughan. If his public paintings became impervious to gay male desire in favour of some other sublimation (I think he possibly saw it in those Freudian terms), it is not just because this would ‘give him away’ in the deeply homophobic British twentieth-century up to the 1980s but because he felt there was a difference between the artist (even the queer artist’s) conception of the male nude in art to that serving purposes of sexual excitation (as explored by Lucie-Smith in different terms (1991:8). Indeed I think Vaughan drew male nudes in 3 different arenas and for 3 different functions, becoming more aestheticized as they moved away from extremely secreted pornography on the first level (Hastings 2017), semi-private eroticism in subjective inter-relationships (Vaughan 1966, Graham & Boyd 1991) and ‘fine art’. The latter had no obvious sexual organs, a number of means of erasure being followed very consciously.

In the latter category bodies are as he intended them following Cezanne’s example (and a reading of trans-historical painterly classicism) such as they example queer art but not art confined to categories like ‘homosexual’ or even ‘gay’ art. It was queer because it still included a formulation of desire in composition, and, at times, Vaughan believed, in ways that could not escape contradictions that exposed art to eruptions of personal desire and which made him see even his art, perhaps all great art, as an expression of ‘homosexuality’ rather than the queerness of desire, which is now visible as nearer to the truth. He wrote in his journals in the 1960s (Yorke 1991:197):

… pages of speculation about how the majority of the great painters of the male nude were homosexual: … how the previous night he, like the Virgin in Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s, had held a youth called Mike naked in his arms in the exact pose of the Christ.

We need to see, more clearly than Vaughan here, what queers the representation of the male nude, probably trans-historically, without silly identifications of gayness or homosexuality before those terms had meaning.

Looking at say the 1970 male nude below, I’d assert that Vaughan’s public art is better than Lucie-Smith (1991) asserts, blaming as he does the heteronormativity and homophobia of the times, and that it was not marred by repressed instincts (to fuller sexual expression) but dug deeper into what the male nude represented homosocial (rather than just homosexual) meanings. Hence his interests in male archetypes: Kouroi, Crucifixions, warriors and noble assemblies. His male figures sometimes emerge from an early set of his photographs from Pagham Beach and there are real similarities between our last mentioned illustration and this one from Pagham.

Pagham pictures included young men whom he related to very differently, including his beautiful (and heterosexual) brother, Dick (an unfortunate name sometimes). We need to see Vaughan though as artist not as repressed homosexual – queer theory allows that – and we then see that these male nudes are very complex icons, or at least that is what I’d like later to assert.

All the best

Steve