Group Biography? Are the stories it tells either valid contributions or good but deficient introductions to a knowledge of artistic movements? Reflecting on Sue Roe’s (2018) In Montparnasse.

Stimulated by reading Roe, S. (2018) In Montparnasse: The emergence of Surrealism in Paris from Duchamp to Dali London, Fig Tree/Penguin

Starting an Art-History qualification in your 60s, which I did last October, is a daunting process. You feel the need of props to very partial knowledge – particularly of the stuff covered by first degrees in the discipline. Hence I lapped up Sue Roe’s In Montmartre covering Parisian Modernism (mainly through Picasso and Matisse). When her third book of ‘group biography’ emerged this year, I thought that might help me in a similar way. I discovered I had missed Roe’s ‘group biography’ of the impressionists. I am reflecting now on why I don’t feel motivated to buy the latter, giving I enjoyed In Montparnasse but in a much more modified way.

I think the reason is that I feel more suspicious of the assumptions made that a ‘group biography’ can be written that illuminates beyond the barest introduction of an artistic movement. Biographies have distinct beginnings (birth and its genetic and social-psychological prequel) and ends (death and a sequel of after death interpretation) that are ideally suited to telling of one life. Since they appeared to be inextricably linked to stories of ‘individual genius, the pendulum turned against the idea of telling biographical stories of artists. It may be that the absence that this opened and the stress on the history of either or both artistic styles or themes opened a door for ‘group biography’. After all biographies are fun: they retell stories that have the value of being seen as ‘true’, however vaguely ‘unreal’. But nowhere is this concept of the ‘group biography’ really defined in a way that can be validated in reading. The two of Roe’s works I’ve read are ‘group’ biographies in as much as they focus, at least notionally, on one geographical place within Paris.

And these formal boundaries are helpful perhaps in limiting the range of our interest in such diverse personages as form our ‘groups’. But they don’t altogether work. Montparnasse is only partially the focus of the latter book, and much less so than Montmartre was in the earlier book. Dali’s life-story in particular (perhaps Gala Eluard/Dali too) strain the biographical limits set by the title, neither being defined by Montparnasse in same way as Picasso was by Montmartre.

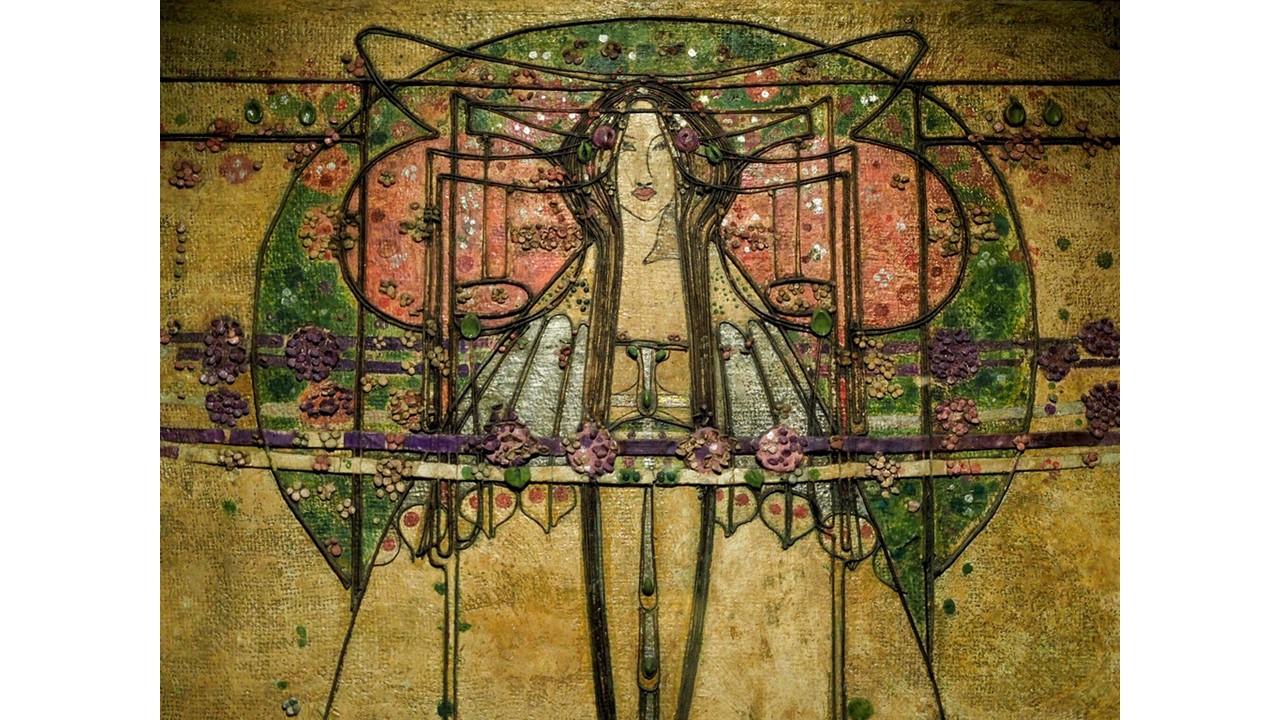

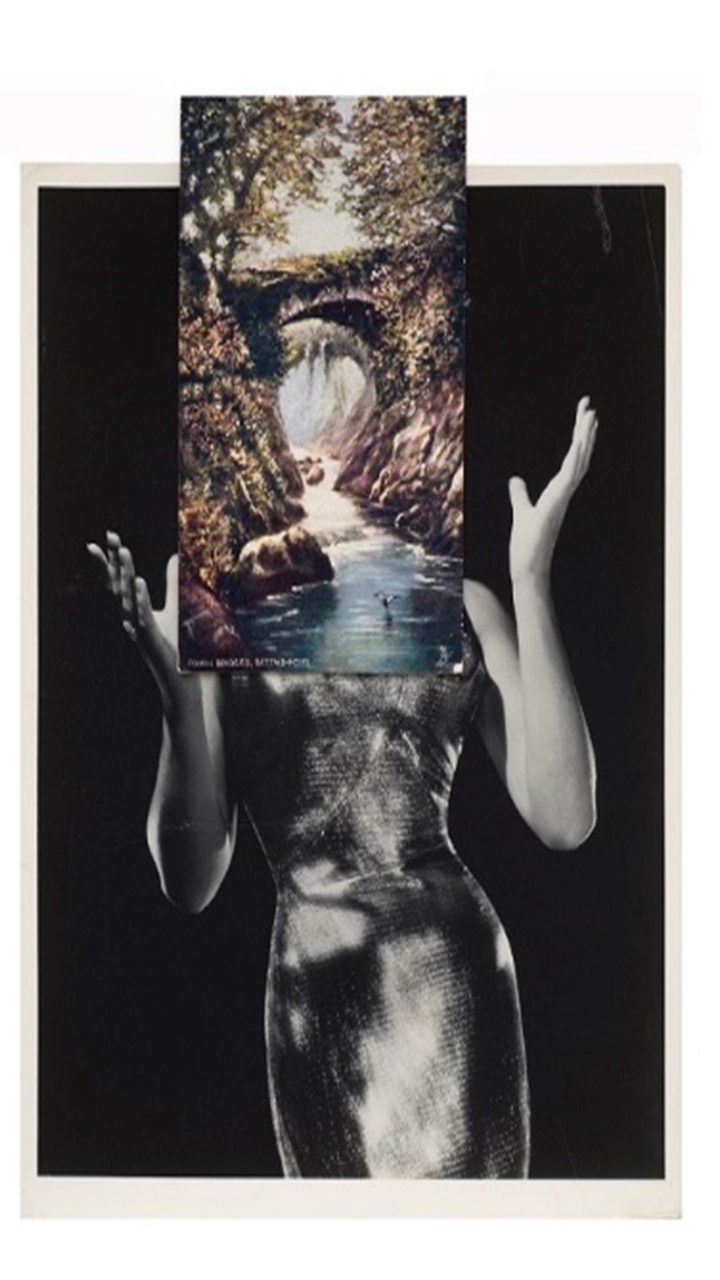

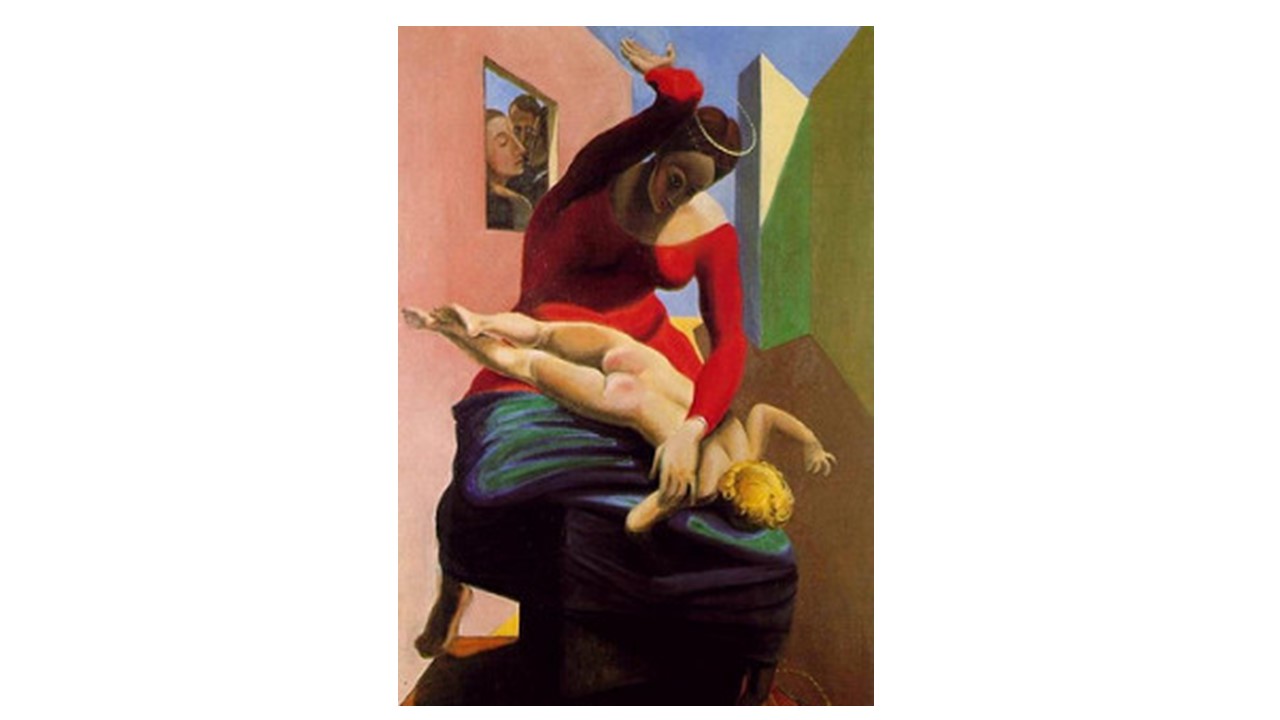

So I found this book stimulating but was conscious of lots of gaps – not least in the ability to compare Roe’s descriptions of artworks with a visual reproduction thereof. The selected illustrations are sparse and tend not to be the ones she writes about with most interest as turning points. I found it too difficult to follow all of the artists with collections of reproductions by my side but found that invaluable with Max Ernst, about whom the Montparnasse book is, in my view, most interesting. However, I reflect that I perhaps found it more interesting because I followed up the reference to each picture – coming across works I hadn’t known that seem to me, as they do to Roe, really boundary-breaking. If not the greatest picture I felt this most strikingly about Ernst’s ‘Madonna Chastising the Infant Jesus in front of three witnesses’. Here a mix of a mock Madonna and a Pieta, told me much about the satiric take on both great Italian Art and the assumptions about the value of punishment in Catholicism. Christ seems to fall off of a capacious knee from the anticipated force of the Madonna’s oncoming spanking blow.

Otherwise I got too much rather racy story with all the limitations that involves. Given this is a group biography of artists in Montmartre who also saw the emergence and merging of Dada and surrealism, it is hard to justify telling the story of the short gay affair between Dali and Lorca (in Spain after all entirely) except for the frisson it allowed. If you are really to tell that story, you needed to do it by contextualising the role of ideas of gender and sexuality across the group, including the practiced homophobia of Breton into which Dali bought. It is all so much more complex – but that goes not only for individuals but also groups. Look to Whitney Chadwick’s (2017) book on ‘Women and Surrealism’ and you see the absences immediately especially of the feminist and lesbian-feminist and bisexual-feminist strand that gives the fuller picture, queered in a way that is less selective than Roe’s narrative[1].

Thus Chadwick tells us of Jacqueline Lambda Breton and her support of surrealism through a love-match (André Breton left behind) with Frida Kahlo. There is also the wonderful story of Claude Cahun and her anti-Nazi life-time female partner (the theme of a great novel this year by Rupert Thomson – a novel so good, it failed to even be glanced at by this year’s eccentric Booker judges) told by Chadwick. These stories get left to the specialist feminist art-historians, but Lorca’s does not (235ff). What is the effect? It is rather homophobic in itself in its rather witty denigration of Lorca’s feelings. Dali, referring to the end of their sexual encounters, tells Lorca to find, she says:

… Surrealism as the ‘one means of Escape’ and told him he should be concentrating on the escape from rational thinking, not the events of the previous summer. (Lorca, devastated, left Spain for New York where, dazzled by the ambience4 of the city, he spent three months writing his first plays.)’

My own feeling is that we don’t need this except as yet another salacious story of oddity. Yet ‘oddities’ (well queerness in general) was abundant in Montparnasse had Roe looked seriously at Chadwick’s pioneering work on lesbian-feminism. It would have deepened and made less prurient I think the story underlying surrealism to include this stories, which, at least in part, touch on Montparnasse gatherings.

Of course biography is selective but in ‘group biography’ the effect of selectiveness is akin to a much wider bias in the account required of themselves by past ‘artistic movements’. What we need is a ‘queer art-history’ of surrealism – one that selectively undercuts joyful recreations of misogynistic stories about Breton, Eluard and Duchamp and that takes Breton’s interest in Marx and Freud seriously (and Dali’s almost fascistic rejection thereof). The role of Etienne de Beaumont might then be more than a colourful story of men who drag up.

Roe’s version of why surrealism might be important to us now (254) is barely comprehensible, since it both seems to prefer the original surrealists to contemporary conceptual art and to rely on a far too vague rationalisation of what surrealism did – which is presumably to delve into the ‘unconscious’. We can’t use that term in the same way Dali and Breton did as Roe admits but contemporary artists now have the discoveries of neuropsychology to help them re-specify the ‘unconscious’ whilst enabling a re-evaluation of Freud (against those old-fashioned cognitive psychologists). They are not merely dependent as conceptual artists (art povera onwards) on the surrealist as pioneers - they have new contexts of thought and social being and should be treated as having such.

[1] Chadwick, W. (2017) The Militant Muse: Love, War and the Women of Surrealism London, Thames & Hudson.