|

A844 - Preparatory Reading |

|

|

Book: |

Mumford, L. (1961) The City in History San Diego, Harcourt, Inc. |

|

How does it reflect on A843 themes? |

It is obviously related to Geography and Institutions primarily, since it looks at the origin and development of cities by investigating how human purposes and needs interact with given landscapes: coasts, rivers, valleys and mountains to produce common forms of the city and how that form changes over time as political & social geography takes some importance in the matter. But it is also about authorship, ‘form’, iconography and meaning and identity to name 4 themes. Can a city’s form be ‘authored’? A key lesson in Mumford is that it both can’t and shouldn’t and that planning of the city is always historically messy and multi-authored (even by people who do not see their agency as crucial to that end 168). When authorship is directly involved it is powerful but mistaken (as in the Baroque as Mumford calls it) imposition of political controls and this is reflected in ‘ideal’ city planners. Thomas More is nearer to the reality of the medieval city than (to Mumford) is the noisome closed and controlling thinker, Plato (159-180), who dares to promote the idea of the city as a (sterile) ‘work of art’. The nearer city planners move to geometry the nearer they move to closedness and control and the stifling of organic development. Not that laissez-faire principles of ‘planning’ are any better – they produce Coketown (447). It is interesting that Dickens provides a lot of the terminology and exempla of the human city (Coketown is created by Dickens in Hard Times but even Wemmick’s suburban ideal is there from Great Expectations). Dickens admired the principle of making things better too, while expecting any development to be still mired in human realities and the ‘messiness’ these produce. |

|

How do I predict that it might foreshadow A844 themes? |

A844 appears to concern itself a lot with art that is very obviously social and cultural, like architecture and decoration. It seems as if it will be about art that is multi-faceted and perceptible in toto only from many perspectives – including those from internal and external standpoints. Hence Mumford’s concern with public politics and its relation to ‘private’ and domestic needs (including sanitation and the role of toilets and hygiene in both realms) will be important, although Mumford’s own ideas are clearly over-focused by the sloppiness of American liberalism (that can extol the importance of Mill’s associative liberalism (572) and yet supports the virtue of US opposition to the regulation of private gun ownership and the primary role of individualism and free will (177, 228f.).

The key focus will be on conceptions of ‘space’ and how these are articulated in architecture and city planning from the vitally important definition of city as a ‘container’ which holds diversity and controls both external and internal threat through disposition of walls, routes and the width of avenues. But also vital is the dynamics of growth and containment of growth that allows him to summarise the medieval in the East (Byzantium) as making a virtue of ‘arrested development’ (241) & say very little else about that beautiful Empire. |

|

What are the books key themes and narratives? |

In a book of this length and ambition there are so many. The concepts I think that will be useful are: · The complex interaction between ‘containment’ of diversity and growth – storage is involved but it includes the dangers of having no containing limits of the latter as in the slummy sprawl of Coketown and the modern Megalopolis of unlimited city complexes where all boundaries are fuzzy (540). In all this there is a recognition of the importance of conflict and its containment and/or release in encouraging growth by association (163 Athens, ugly coercive discipline in the Baroque 363 and its ‘sterility’ 406). The role of theatre and drama in all of this (70, 378f., · The contrast between city ‘bildung’ and ‘unbuilding’ (Abbau 451). This is very complex, and I don’t yet understand it. But the latter is associated with the destructive potential of quantifiable masses of ‘atomic individuals’ and the economic role of mining and large industrial agglomerations of people and buildings whose functions deny the value of appearance and begin to utilize the underground (479). · The contrast in city planning function of the contrasting processes of ‘materialisation’ (where ideas become the built environment) and ‘etherealization’ (where ideas themselves serve as a means of limiting their materialisation in buildings). This runs throughout starting at about 319. These ideas seem related to material buildings like walls, monuments, temples and politically sacred monumentalism. Materialisation is at its apex in Baroque – which Mumford sees as emerging from the Renaissance (not seen as ‘rebirth’). · The holistic review of cities as a form of space management – transport takes up space that could be used for living for instance (407, Medieval principles (occidental) 288-299)). See functional zoning explained by Venice 623, in preparation for its less humane form in Coketown 446. · The definition of ‘monumentalism’ as a ‘materialisation’ of sacral, civic and memorial ideas and practices – especially in ‘museums’ (199). In modernity the role of ‘processing mechanisms’ as a substitute for real human association especially in universities 542. And probably many more. |

|

How does the book relate to the analysis of art and architecture? |

There are specific analyses that are of useful weight such as the discussion of Athens, Rome, Venice, Amsterdam and London. The interesting thing is that Mumford does not focus on any building separate from its functional and ideological context – especially in Baroque. Moreover, no building is representative of a city if we miss the importance of non-monumental architecture meeting the needs of continuing domestic life. No place is just a ‘showplace’ 177. The attack on fashionable expression is at its best (but surely questionable) in its ‘analysis’ of skyscrapers (plate 46, 430 and the genesis of ‘high rise’ in well-intentioned Peabody initiative 434). The contrast between outer appearance and inner life-reality (197). The analysis of Charlotte Square (399) in Edinburgh as merely façade (and the truth of Baroque) is masterly. |

|

Any other points! |

There are so many - so perhaps none is better here. The expression through aphorisms is appealing but warns (especially because of the necessary abstraction and generality of some of the ‘analysis’ and its omissions) of the possibility of intellectual sloppiness. You admire the phrasing of: ‘Knowledge … externalised in museums and libraries…’ (199) but you need to keep open a view that more specific analysis of specific museums and libraries will reveal much more fine-grained truth that might invalidate the generalisation as such. |

Other preparatory reading completed:

Benedict Anderson Imagined Communities (click to see in new window)

Schama Landscape & Memory (click to see in new window)

Conway & Roenisch Understanding Architecture (click to see in new window)Elkins & Naef (Eds.) What is an Image? (click to see in new window)

Moxey, K. (2013) Visual Time: The Image in History (click to see in new window)

Aynsley & Grant (Eds.) Imagined Interiors (click to see in new window)Boswell & Evans (eds.) Representing the Nation (click to see in new window)

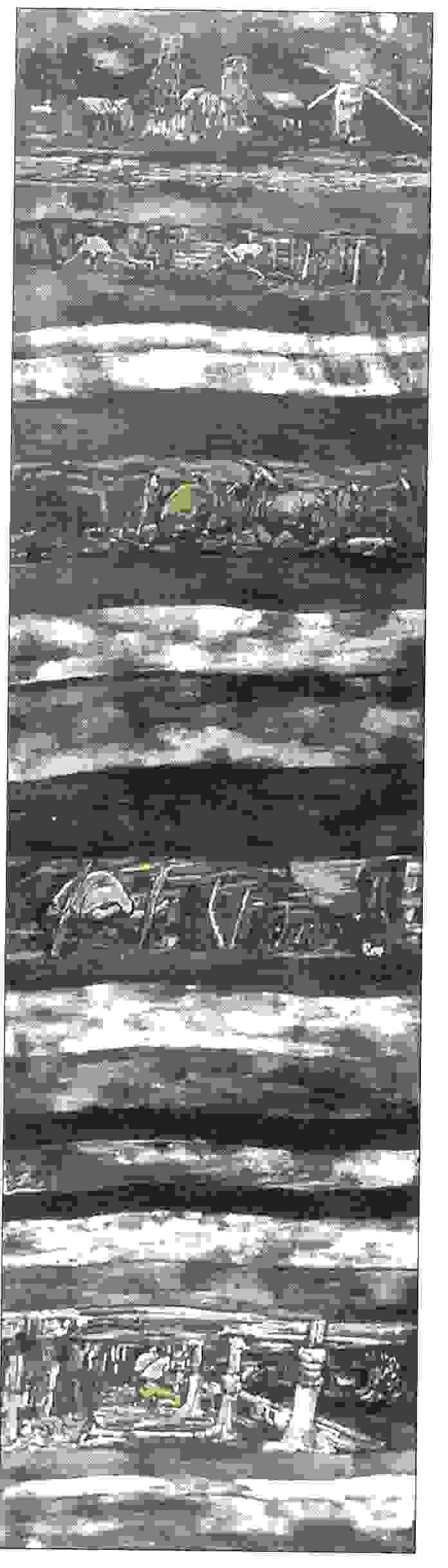

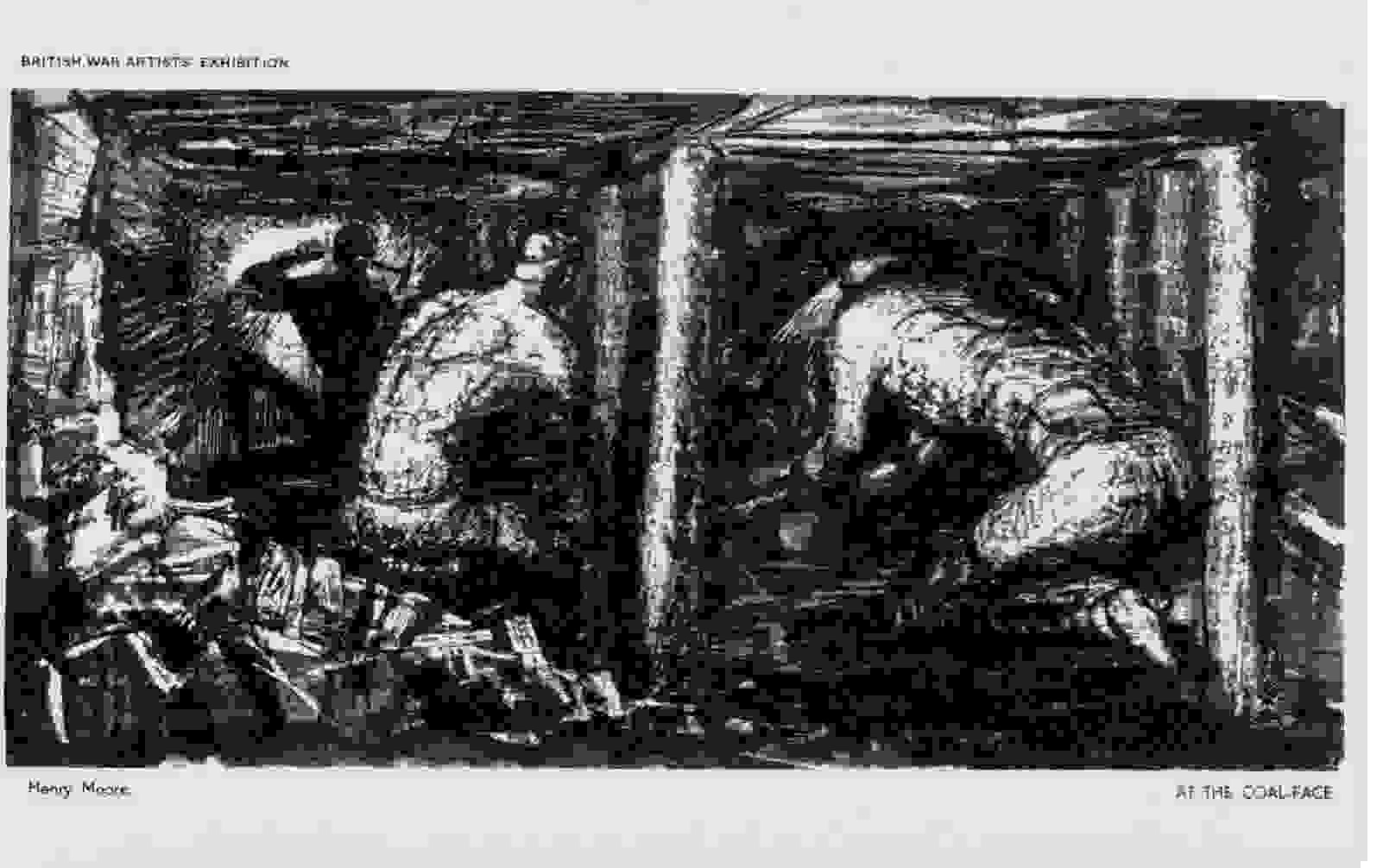

McGuinness was known to believe that Henry Moore, an artist

he admired, got ‘some things wrong’. One if those things, in my view is the

attempt to know or cast light on miners. This emerges in the very unreal light

sources utilised in Moore’s mining pictures.

McGuinness was known to believe that Henry Moore, an artist

he admired, got ‘some things wrong’. One if those things, in my view is the

attempt to know or cast light on miners. This emerges in the very unreal light

sources utilised in Moore’s mining pictures.