Personal Blogs

Meaning in Production text in https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=198558, Open that in new window by clicking here.

It was typical

that I not notice that the task I chose did want meaning to be covered –

although this was covered in the wording of Option 1 rather than the categories

given for write-up.: ‘try to do some analysis of the resulting image(s)’.

So here is a first of a series (if I ever take it further) of iterative thinking about my collage.

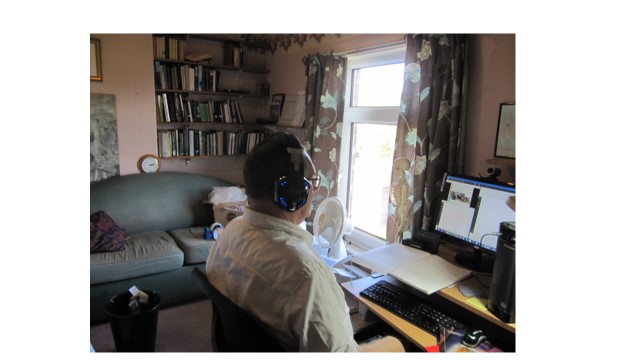

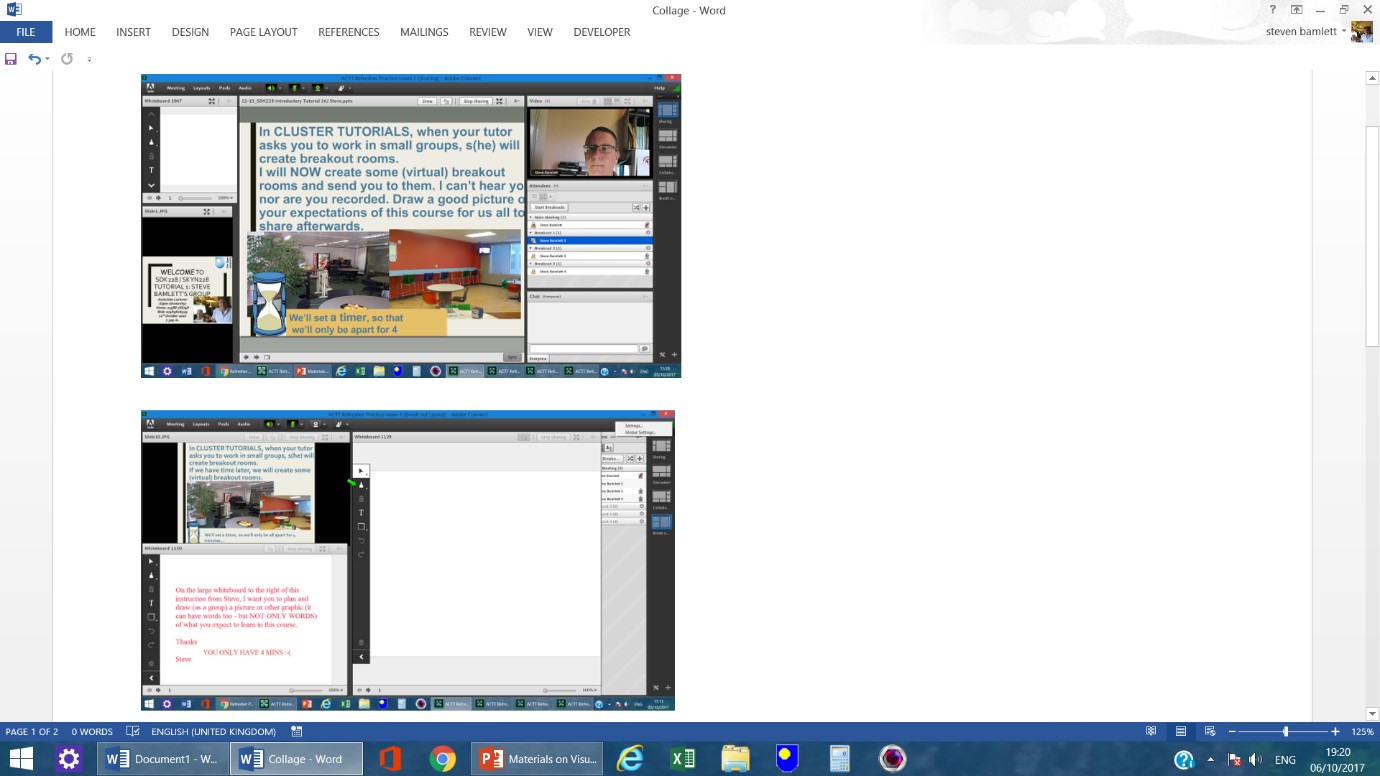

a) In both the online screens and the photographed offline location there are phenomena which call themselves ‘rooms’ that can be ‘entered’. The latter is a physical room in which a lone worker sits. The former (on the screen-prints) is of 2 online ‘rooms’ – the first is the ‘Main Meeting Sharing Layout’ (as designated by Adobe Connect [AC]) and the second (under design by the worker) is a ‘Break-Out Rooms layout’. This same layout (Fig 2b) will be demonstrated in the Meeting Main room (following the scenario represented in Fig 2a), and then will be used by three or more sub-groups in their individual ‘Break-Out Rooms’. Both online and offline rooms can be said to be entered by the participant (SB). In what sense are the action of ‘entry’ or the space indicated as ‘room’ related to each other in offline and online space?

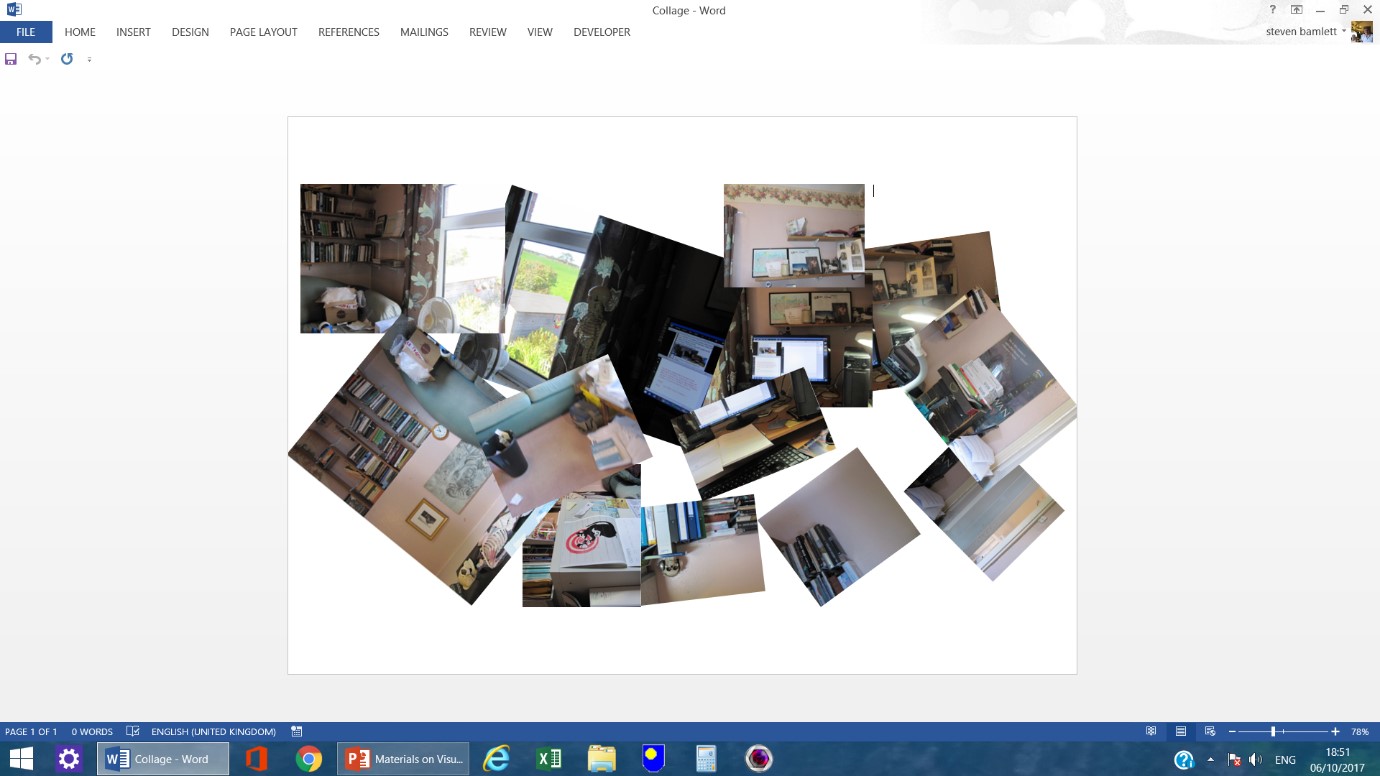

b) The physical room is distinguished by ‘space’ apprehended through various perspectives on its interior distances. These involve perspective, dimensionality and orientation. The camera representing the participant looks up, down (although these latter tend not to be represented in the collage). Each perspective as the cameras ‘sees’ it are influenced by the direction of light that illuminates the ‘room’ and makes its contents visible or obscures them in shadow. Those conditions of light are effected by spatial and temporal distance of the light source (a window to a garden, garage and field beyond and a desk light). The variation in perspectives fragments the whole so that our whole impression of the room is ‘mocked up’ as a whole whilst making clear the partiality of the grasp of each part of the scene to the pauses in the movements of the camera ‘eye’.

a. Thus note how a central slide which looks down upon the computer desk in front of the computer monitor shows the light reflecting from the white page of the participant’s diary. The proximity of diary and monitor are related to the temporal space that the screen shots represent – they are designs for a session that the participant is committing to hard record in the diary. Likewise, the participant plans for future practice sessions in order to come to terms with how to engage with the transition between Main Meeting and Break-out room (which was revealed as still problematic in this session). For the participant, what is being manipulated on the screen online has a ‘close’ relationship’ to the planning of temporal space in the diary. The screen itself in the shot above is relatively dark – the camera eye responding to the greater light source at a nearby window. We see the break-out room represented on the monitor but that ‘room’ is, in this view, subsumed to the perception of the computer monitor as one of the many objects in the room that might articulate themselves and their relationship to the participant.

b. Objects in the room and their spatial relationships can tell us something about the consciously and unconsciously displayed aspects of the participant’s identity. The house and garden bespeak something about class and status. However other issues are betrayed by the books on show, the formal placing of wall decorations and the informal placing of objects and mementoes, including postcards and photographs.

c. Time is central to the last point. Dead parents and pets, lost interests (the occluded Whitman) is displaced by the postcard of the Scottish hunk. The meanings of the placements can’t though be determined without some view of the subjectivity, and its changes that caused their spatial placements over time. Moreover, how much of that placement was planned or ‘accidental’ (if accidents exist in psychology) without involvement of elements of subjectivity including cognition and emotion. But temporal changes that aren’t subjective will also have been determining those placements: change of jobs, friends and the growth and development of children – the pictures above the monitor are by ‘children’ long since entered adulthood. This point about time is true of the book selection which tells of what book survived different course – in Classical Literature, philosophy, art (Van Gogh in presence) and so on. The old Soviet peace poster recalls a past holiday in a long ‘gone’ country as do the Byzantine church models and life and educational certificates

d. Determining the balance of literary mementoes and ‘scientific’ ones and interpreting what kind of boundaries there may or may not be can be posed by the 2 skeleton models and the brain next to centrally but upwardly placed neuroscience texts.

e. And then it is clear that the room is not well-tended – bearing sciences of decoration from a past that is not the participants but of the house containing the room, the clutter and over-use of floor-space as a temporal storage during a work phase – showing the badly organised remains of different interests which could be those of the participant or his husband.

f. IN CONCLUSION, an offline room is complexly organised in terms of both competing and collaborating interests of the participant and their immediate networks. It means emotions, thoughts, memory and forgetting, past and present lives and work roles, institutions and so on. Here the computer keyboard and monitor fit into the meaning of an object required by the participants work (very salient at the moment of the picture) and home-life (eBay stores of books now read and no longer having a space anywhere in the house).

c) The offline rooms are located in what we might call cyberspace – but the role of metaphor here is important. The Internet does not require the idea of architecture or rooms but hierarchical organisations of education (universities do). I notice with some surprise that the idea of room architecture is employed as a self-labelling metaphor in both rooms and to connect them to each other. The break-out room event is represented symbolically in 2(a) by pictures of two rooms – taken from Google and with no knowledge of what they represent. In part they were chosen so that the institutional language of main meeting and break-out rooms can be visualised and absorbed. However, it was also purposeful to show two different rooms – to emphasise that how digital meeting-space is conceptualised is both arbitrary, can be different for different people in the same space, and the conceptual sequelae of that. Those sequelae are that online spaces can be used in ways that offline spaces cannot – to destabilise space by linking to other places / resources / pages. However:

i. It is not true that you can control spaces. It depends on your status in the VLE hierarchy (Host, Presenter, and Participant – each with diminishing powers in that sequence). Since both screenshots are in ‘Host’ view controls that would allow this are visible in the in the top icon bar. However, were this scenario seen by a participant, even avatar participant as I discovered, those controls are diminished such that one follows a top-driven agenda. Hosts can gift and take away privileges to anyone below them, whether these gifts are requested are not – even in Break-Out rooms the agenda remains firmly in the hands of the Host and s (he) can visit each room as s (he) wishes. The breakout room reminds participants in them, by the placing of an icon to the left top corner, the main meeting to which they will return on the Host’s decision (as do timer and fixed – unchangeable instructions)

ii. It is clear that Bayne’s view that some metaphors for space here maintain functional fixedness in the educational space – they connate not multiply determined space (as in the physical room collaged) but one determined by ‘convention’ and, of course hierarchical power relations in higher education. I appear to be aiming here to a Baynesian reading as referenced in the earlier blog.

ENOUGH FOR NOW

Steve

‘To Enter

a Room’: Researching Space & Entry into Space in an

exploratory exercise by one OU Tutor preparing an online session on newly

introduced software (Adobe Connect).

‘To Enter

a Room’: Researching Space & Entry into Space in an

exploratory exercise by one OU Tutor preparing an online session on newly

introduced software (Adobe Connect).

Steve Bamlett

Image Creation Exercise

To see the Meanings found in Production text described below, see https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=198642, Open that in new window by clicking here.

The two images I will be examining in this blog post are on pages 2 & 3.

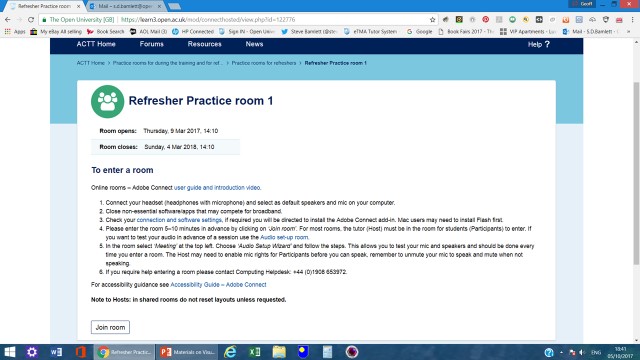

1. This is a collage of photographs that aim to show a series of views of the room space taken in a 360o swirl in an office chair. The room space is that in which teaching preparation happens, including representations of offline space and access point to online space at one point in the preparation process (p2).

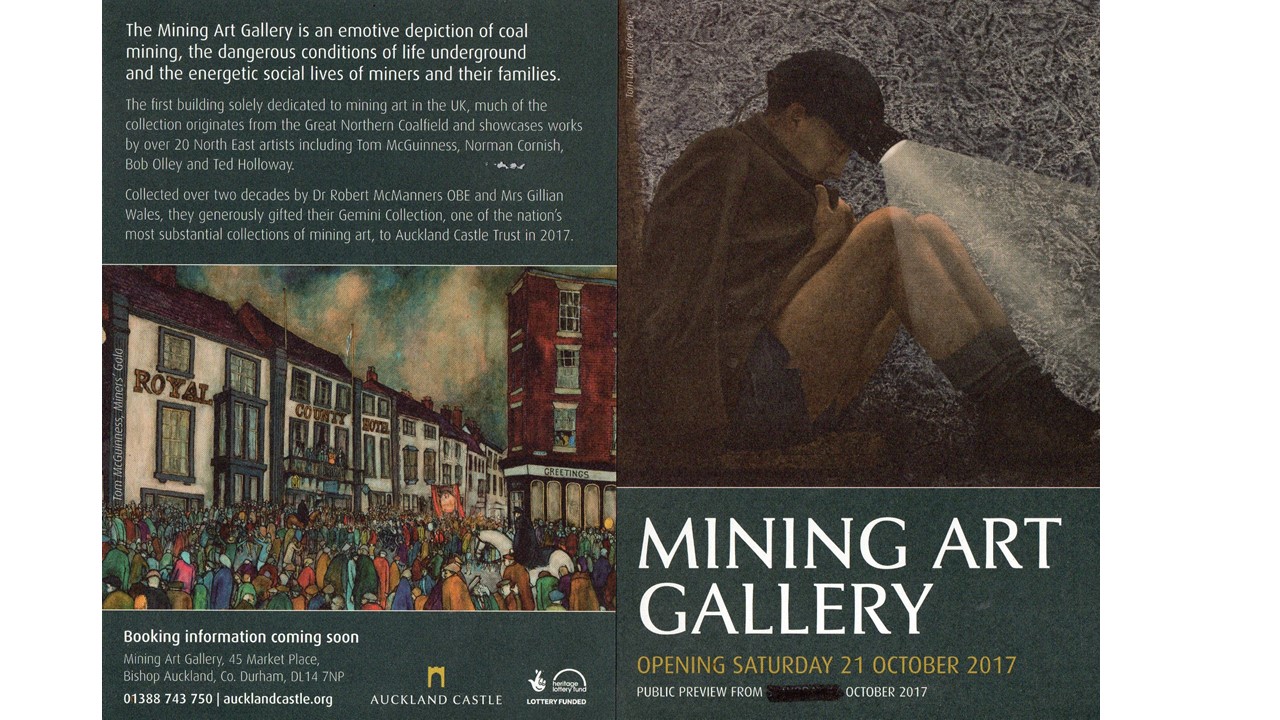

2. This is the online space used at this same point, as well as an explanatory online pages (p3).

The exercise took place on Thursday 5th November 2017 at 1419. Steve started work on his preparation. A random time by his husband, Geoff, was chosen from a set of folded identical papers well jumbled. The purpose of this ‘randomisation was so that Steve would not know which window would be open on his computer at the point when the photographic data was collected. Had he known this, a window could have been chosen that illustrated a pre-determined set of meanings (at least potentially)

The

Task set & option chosen

Option 1: Collect and analyse images. Take a tour of your workplace or your neighbourhood with a camera, create a collage of images that represent a particular concept or theme you are interested in exploring. Then, write a blog post about your image creation task. Importantly, try to do some analysis of the resulting image(s).

Think about the following questions as a way of structuring your writing:

· What is depicted in the image(s)?

· What were you trying to discover by creating your image(s)

· What did the process of image creation involve?

· What is not seen, and why?

· How is meaning being conveyed?

· With respect to the photographs, how might the image(s) convey something different to your experience of 'being there'

The Task

- What

is depicted in the image(s) – Figs 2 & 3 above?

Fig 2 is an amateur’s attempt to create a ‘joiner’ (a method of assembling overlapping photographs to represent the collision of different perspectives to create a ‘whole’ but fragmented vision). David Hockney (2007:102) argues that such works use theories of seeing originating in in Analytic Cubism under Picasso, Braque & Leger. They show the participant’s spatial environment(s) at 1419 during a preparatory session for an online meeting with a group of 22 Level 4 learners to be held in the following week. The method used is dependent on the viewer’s perspective during a sequence of pauses in one 360o chair swivel the whole picture since, unlike Hockney and others, it also involves views to the back of the participant at 1419 and are represented by a swivel of their frame in the median range of 180o. The technique was intended to picture ‘space’ and ‘room’ (and a ‘room’) following Hockney’s experiments (but by an enthusiast amateur with no artistic pretension) that was, in effect ‘moving the space about’ (Hockney 007:106).

This is a deeply ‘subjective’ act but that in itself is not a problem with the method, since it aims at capturing not measurable space but perceived space, which may be an interaction with both filmic space – all depths are brought to the surface in a photograph and interact with ‘illusory’ effects of light - but also an element of potential psychological space (within any conscious or unconscious decisions made in taking and framing the picture and then selecting it or not for the collage).

The reason for not selecting an image (the repertoire can be seen on the attached file), the participant – analyst believed that these images could not technically fit on the A4 page on which cropped versions of them were mounted. The cropping was guided, it was believed, by an attempt at minimal fragmented continuity of the photographs.

Near the middle of the picture is the computer screen on a computer table, which was the primary focus of this observation.

Figure 2(b) is a print screen of the new layout being created for breakout rooms to be used in the teaching session. These are in incomplete form but are, I think, near, completion, although the Attendee pod will not be present. Note that attendees in this creation mode and in 2(a) are the participant (as Host in control of dependent views available to participants). The participants are all ‘avatars’ of the participant created by successive room entries.

The move to the Breakout rooms in 2(b) when completed will follow the screen in the main meeting at 2a. In each case a photograph representing the parent screen is available in its own pod. The breakout screens will ideally be used for instruction before participants are despatched to breakouts – especially in introducing the drawing / writing icon tool-bar (this is their first tutorial on the first year of AC’s introduction to the OU). I ought to say that the latter sentence indicates my plans if this is possible but I am not totally sure yet – more planning to do.

The screen (2b) at 1419 was in a state of near completion. Note that since this is a HOST screen there are some icons in the top bar not available to learners in the breakout rooms, which allow the creation, control and destruction of this new layout by the Host.

It had been pre-planned, but not with an eye to this project, to work on breakout rooms. I have long puzzled on the spatial / architectural metaphors such as ‘room’ used to describe cyber-space or online space and puzzled about them on my MA in Online & distance education (click to open in new window).

- What were you

trying to discover by creating your image(s)

In my blog (Bamlett 2016) – link immediately above – I quoted a sentence I removed from my EMA (which didn’t do all that well! L cheer upJ). It was:

Lucas & Claxton (2010:99) identify ‘functional fixedness’ as a means of disempowering learners from grasping more than the obvious affordances of resources. They see it as endemic to cultures dependent on teaching-to-the test rather than ‘lifelong-learning’.

I think it is possible that one means of achieving ‘functional fixedness’ is to control the spaces that learners inhabit online and indeed offline. What is space and what is 'a room' or 'room'? How do formal and informal definitions of these terms impact on learners online? How do offline contexts relate to online contexts in the learner’s conceptualisation and use of space? How do ideas of control, order, organization, and conversely, ‘creativity’ or individual difference – perhaps aspects of manipulations of psychological space - interact with other formal and informal spatial definitions?

These questions are all MUCH too large and vaguely posed. Moreover, I probably have no intention of following them through. They are not new questions to the academy though. Collier & Collier (1986: 46ff.) example such questions in ‘visual anthropology’ as early as the 1950s. Indeed Hall’s (1966: 97 words cited ibid: 48) seem to sum up my own study:

People who “live in mess” … are those who fail to classify activities and artefacts according to a uniform, consistent, or predictable spatial plan.’ (Mea culpa!!!!!!)

Together with these are much newer questions in online education: notably those in Bayne (2008:403) who shows how some VLEs strain to ‘render the “unknowability” of digital space knowable … in a way that is heavily coded for stability, authority, and convention, and which limits the sense of the information space as a domain’ from the intrusion of radical alternatives.

There is no doubt that what I want to produce however is only notes towards these issues. My MA in Art History has like ‘la belle dame sans merci’ ‘me in thrall’.

- What did the

process of image creation involve?

I have detailed the process of ‘reconstructing’ images into a ‘production text’ (Fiske 1989 cited Mitchell 2017:92) above at various points. Of course in a write-up I’d go for a fuller Methods section here, included deeper thought on analytic methodologies – my preference though would be a form of multimodal analysis (Bateman 2008, Bezemer & Kress 2016).

- What is not seen,

and why?

The unseen here is vast, even though the method aims to highlight the perspectival nature of concepts of offline space. Indeed an addition to the method may be to ask participants in open interview ‘what do you think is missing from your collage that would help someone to understand your experience better?’ What I think is missing here (given that I did this quickly and as a pilot to see how to refine the instructions to myself) is that psychologically vision is not experienced in this angular way and that gaps in the layout appear not to be meaningful – see, for instance, how Hockney uses gaps – and their absence – in his ‘joiners’. The kinetics and proxemics within the space obviously also have meaning, since movement, even eye saccades, will serve psychologically to make the objects and environment meaningful to the person viewing them. A kind of dance animates meaning and image production. This is even more problematic when you consider how the contents of a screen are seen in interactions with the objects that ‘contain’ it and surround it or are called forth by it. Some pictures could not be integrated in the collage, yet one, showing a pile of papers on the floor, topped by my copy of Coe et. al. (2017) obviously must have an impact on meaning production – its absence being significant.

- How is meaning

being conveyed?

Meanings may be thought to be conventionally attached to objects and artefacts in the ‘room’ (and indeed the room itself, which was obviously once a bedroom – well before we moved here (why do we never decorate?). Meaning will be an interaction between top-down stored associations and bottom-up perceptions. Untangling what we see and what it means is necessarily a subjective and iterative process where meanings are tried out. Such a process will involve deep reflexivity in the process of interpretation and contain information to help the reader find out how interpretations might be motivated by interest (gender, sexuality, class, status and so on). What is discovered might not be unpredictable to the viewer’s expectations as a result. One effect of changing perspectives on a moment is its defamiliarisation, possibly as a result of mental processing involving wider networks of association than those usually employed.

- With respect to the

photographs, how might the image(s) convey something different to your

experience of 'being there'

My last sentence in part covers this. However, it is also important to remember that the viewer may already have chosen a ‘meaning’ of their experience prior to having it: in order to meet the ambitions of their academic project or for a more or less conscious reason. Hence devices to increase reflexivity including peer involvement in analysis may well be important.

PS I have my ideas about how, at this point, I interpret my ‘production text’. I’m so pleased we aren’t asked to make this analysis. Happy to discuss though.

What fascinates me are the self-images in the created cyber-rooms shown (especially Fig. 2a). I’d like / not like to think about that!

References

Bamlett, S. (2016) ‘Education as Space-Travel. Referred to in H817 EMA as Bamlett (2016c)’ in ‘Steve Bamlett’s blog: Available at: https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=178400

Bateman, J.A. (2008) Mulltimodality and Genre: A Foundation for the Systematic Analysis of Multimodal Documents London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Bayne, S. (2008) ‘Higher education as a visual practice: Seeing through the virtual learning environment’ in Teaching in Higher Education 13 (4) 395-410 DOI: 10.1080/13562510802169665.

Bezemer, J. & Kress, G. (2016) Multimodality, Learning & Communication: A social semiotic frame London, Routledge

Coe, R., Waring, M., Hedges, L.V. & Arthur, J. (Eds) 2nd ed. (2017) Research Methods & Methodologies in Education Los Angeles, Sage.

Collier, J. & Collier, M. (1986) Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press.

Hockney, D. (2007) Hockney’s Pictures London, Thames & Hudson.

Lucas, B. & Claxton, G. (2010) New Kinds of Smart: How the Science of Learnable Intelligence is Changing Education Maidenhead, Open University Press / McGraw-Hill Education.

Mitchell, C. ‘Visual methodologies’ in Coe, R., Waring, M., Hedges, L.V. & Arthur, J. (Eds) 2nd ed. Research Methods & Methodologies in Education Los Angeles, Sage. 92 – 99.

It should be apparent

from Nesbit’s title that her essay is, in some sense, a retort to Foucault’s

influential ‘What is an author?’ As you read try to keep this dimension in

mind. Ask yourself, and include in your notes:

· How does her account differ from Foucault’s perspective on authorship? To put this another way, what is her dispute with him?

· How does copyright define biography/authorship? How does it change?

· Why does Nesbit employ the past tense?

1. Style is important in

comparing this essay to Foucault: ‘The French definition of the author has gone

vague …’. We begin with a very relaxed response to what ‘some say’ about an

author, including the characterisation of Barthes infamous notion of the ‘death

of the author’ – ‘some say corpse’. This rather deliberate undercutting of your

antagonist (a kind of reduction ad absurdum’) is as near to the allusiveness of

Barthes and Foucault as is gossip to formal debate. It mimes the ‘crudeness’

(229) of which it speaks. This then is stylistic control of a high order, which

tries to show that author-functions (the plural is indicative of what is to

follow) are implicit in the work but may be multiple, rather than singular. It

shifts the question from, in the last analysis, what are authors in relation to

a work – even, we might say, somewhat reflexively, the work you are now

reading. The use of an authorial ‘we’ in this essay is probably as worthy as

study as anything else in it.

The substance of the dispute with Foucault appears on pp. 240ff.and again starts with an allusive wit. In mounting a case that Foucault does not cite law specifically as a means of explaining the socio-cultural function of an author: “to characterize the existence, circulation, and operation of certain discourses within a society” (cited 240). Nesbit riffs, in the stylistic register of the detective –fiction genre. Foucault does not ‘call in the law’ to investigate the death of the author but prefers like any old private dick to do the job himself.

We are left with a deeper critique than we might suppose. Foucault assumes authority in order to question it, and, Nesbit suggests, thus fails to see how, in the end, even his own function is socially inscribed in determining economic practices – market regulation in the name of the law. Author functions are called forth by the relations of supply and demand in the economy: ‘Authors function, whether the state of knowledge recognizes their existence or not.’

This is so beautiful – in turning ‘author function’ into ‘Authors function’ we see that function in relation to the economy of desire (another term for supply & demand). Nesbitt says Foucault fails to note that discourses are not superior to the ‘market economy’ and are indeed their locus of being: indeed ‘this economic condition … defined the author in the first place (240). Author functions are determined (or in Althusser’s use of the Freudian term ‘overdetermined’) ultimately by the economy in Nesbit, who goes to insist that law is, at some level, the primary political articulation of this changing economic condition. The ‘state of knowledge’ ruled by Foucauldian authority forgets that its ‘state’ is merely transitory and ultimately determined (‘in the last instance’) in determining socio-economic practices such as the market. It is a state therefore in deep political peril.

Nesbit therefore argues, I think, that history, through mutating legal discourse, does not provide an authoritative definition of the author and their work but a determining ‘working definition of art’, which has been ‘as a quantity not a quality, the zero-degree of the law’ (241). Her conviction is that Foucault is blind to this because he is blind to any perception of over-determination, such as is argued by Marxism as a totalising analytic philosophy. As the economic bases of an economy slowly change, so do, by necessity, the laws which maintain stability are slowly changing, either in the direction of the consolidation of notions of individual ownership of intellectual property or capital (235) to one where capital is aggregated from interest groups working in uneasy collaboration (in the present day [257]). In this present context copyright law is barely able to form a coherent statement, not least about what an author is. What I think is suggested here is that the author is seen as a conflicted concept at present and that, it is in this conflict that there is hope of beneficial historical change, in which cultures differentiate in the very act of coming together (257). This provides a source of postmodern change not available to the more structuralist theories of Althusser.

My concern here is that Nesbit rather reifies the law and its ability to speak in a unitary voice. The law speaks only at the moment of its interpretation (in court) and otherwise lives in an interpretive vacuum, using only tools enabling its texts to be read and these in themselves being largely past interpretive moments (the role of legal precedents). Law in practice is often defined by discourses other than itself – including professional discourses. If we fail to see that, we fail to see how a liberatory law for those with queried mental capacity in 2005 has become a law that articulates mainly how ‘deprivation of liberty’; can be justified – following revisions in 2010.

2. Copyright defines biography’s relationship to authorship by ‘flattening’ any differentiations one might want to make between authors’ biographies which other discourses, such as those of connoisseurship: high art, lower art and non-art; genius or non-genius; or good art & bad art. It reduces authorial function to a set of rights ‘to a cultural space over which he or she may range and work’ (230).Thus photography is defined not by its concomitant devices (such as the camera) but by the photographer’s ‘work’ understood as his or her ‘property’. (237). This could be extended since Nesbit here falsely names the camera device as the main progenitor of photography as an art, whereas it was in fact the means of imprinting durable images produced within the camera. There remains a lively debate about the role of the camera in visual art since Brunelleschi, Caravaggio and Vermeer. This debate however would perhaps not shake Nesbit’s main point. The artist’s ‘eye’, ‘hand’ and their especial interaction remained a means of enforcing hierarchical distinctions, since it was conceptualised as a valorised and distinct type of interaction through virtue of nature, nurture or both.

3. Nesbit employs the past tense for a number of reasons I think.

§ First it acts as if the author, being dead according to Barthes, can only be a past phenomenon. In this sense ‘was’ is past perfect in tense.

§ Second the ‘was’ might be a past imperfect tense. In this sense it does not ask what was the author when it existed but what was the author in the past compared to what the author is now and will be in the future – it was once that but it now is … and may become … (re-establishing the dynamic dialectic of history in Marx over Foucault’s archaeological metaphor for it.

§ It riffs on Foucault’s title. Foucault says what ‘is’ an author because he remains that type of author established by the Old law (as, more tragically, does Barthes). He does not know that he sings of his own obsolescence – believing that the hall of discourses (the university) trumps historical changes in the economy and the new law that will articulate it. Atget’s and Duchamp’s ‘common-sense’ appreciation of art is favoured over theirs as more historically accurate, timely and sighted out of the old writer’s ‘blind spots’. It establishes a new wave of Marxist cultural analysis: Lyotard to Nesbit.

That’s me, done though.

Steve

Consider the following extract from Lakanal’s report on the French copyright law of 1793 and try to identify the central concepts he uses to argue for special rights for authors:

Of all properties, the most incontestable, the one whose increase is in no way injurious to Republican equality and which gives no offence to liberty, is undeniably the property of works of genius; it is if anything surprising that it should have proved necessary to recognize this property and to secure its free exercise by a positive law, and that a great Revolution like ours should have been required to return us, in this as in so many other matters, to the simplest elements of common justice.

Genius fashions in silence a work which pushes back the boundaries of human knowledge: instantly, literary pirates seize it, and the author must pass into immortality only through the horrors of poverty.

Ah! What of his children …? Citizens, the lineage of the great Corneille sputtered out in indigence!

Since printing is the only means whereby the author may make useful exercise of his property, the fact of being printed alone cannot make an author’s works public property, at least not in the way that the literary buccaneers understand; for if it were so, it follows that the author would be unable to make use of his property without losing it in the same moment.

What a cruel fate for a man of genius, who has dedicated his waking hours to the instruction of his fellow citizens, to receive only a sterile glory, and to be unable to claim the legitimate reward of such noble labour.

It is after careful deliberation that this Committee advises you to create dedicated legislative provisions which will form, in a sense, the Declaration of the Rights of Genius.

(Lakanal, 2008 [1793], p. 176)

The passage works by setting up an assumption that property and capital accumulated by certain individuals may be the source of significant inequality (and, unsaid) oppression). In a sense, that is the meaning (at this time at least) of the revolution – in that it challenges the control of land, objects and more fluid property by a minority – those who call themselves the ‘best’; the aristocracy. Aristocracies may be set up by accumulation of property in the hands of a few, but the French Revolution here does not declare that property is itself a problematic category: where ‘all property is theft’, Instead it implicitly declaims that property ownership be determined according to the ‘simplest elements of common justice’.

This belief in property rights as inalienable rights will become the trademark of bourgeois revolution. It institutes itself on a belief in unequal distribution of talents, founded on the example of ‘genius’. Genius is never equally distributed – if it were it could not be recognised as such and there would be no reason to separate our feelings about the fate of Corneille’s children from those of the children of every (wo) man. And if our belief that intellectual property is the ‘most incontestable’ can only be a step away from a New-Right justification that property itself is not the source of inequality rather the natural and qualities of its holders.

The passage is a defence of ownership in its crudest form and applying to objects that are unseen. A printed work may be an object that can enter the free market but its contents represent that which naturally belongs to the ‘author-function’ – that work which alienates (in silence) the author’s internal property and makes it appropriable unless its ownership be legally protected as a ‘right’. If we believe in the ‘Rights of Man’ (sic) then (assuming that only some men are genii) the rights of genius are also an obvious corollary of those rights and we are a step away from copyright law.

We have reinstituted a kind of aristocracy in the name of equality – a contradiction worthy of a true bourgeois revolution. Such a view must be music to a ‘genius’ like Marat or David.

An aristocracy of Nature. The masturbatory image of Corneille sputtering out his semen as waste is at its root – a right of man indeed. What we requite is a coming together of the law (legitimacy), the recognition of ‘natural’ inequalities of mental capital as an incontestable basis for seeing labour in acts of mental control in a recognition of inequality as the basis of an ordered society – at least of bourgeois society. This is the tragedy of nineteenth century France. The peasants die for a fraternity of capitalists (come back Zola – all is forgiven – even what you did to Cezanne!).

· What kind of topics are you interested in

researching?

As far practical research in the world of work, that is no longer an aspiration for me. However, my residual interests in the nature of research into health and social care remains, even though I never during my career found a context of research in this area that focused on a multi-perspectival approach to the psycho-social world that I once felt to be such an urgent need. The work I do part time (AL at the OU) that introduces methods remains either thin (at undergraduate level) or focused on quantitative approaches that actively excludes qualitative work at any depth (in conceptualising data collection and analysis). I teach a course on Mental Health (aimed at part at nursing and social work trainees) that virtually invalidates the kind of qualitative analysis, which I find most useful as a mental health practitioner, survivor or learner.

My present involvement in study then is mainly on an MA on Art History, which does at least raise issues fundamental to my interests – such as the role of multimodality in teaching, learning and research. In the end then I plump for that as my main interest. As you will see below, I kind of resist the ‘research question’ approach because I think my current interests are fulfilled by the speculative, intuitive and reflective examination of the limits of research for my needs were I ever to try and realise them.

· What initial research questions might be starting to emerge for you?

How can multimodal input into teaching and learning be used to engage, motivate and raise expectations of ‘self’ and the ability of practitioners to practice with a more critical sense of what evidence is important in work with people who identify as having mental health problems?

I understand that this is too large, but I am not at the point of knowing how to ask the researchable questions, which might evaluate current or past implementations of multimodality in teaching or learning, as well as attempting trials of newer interventions.

In a sense I do trial and error (with safeguards) in my present work as a teacher in this vaguely conceptualised direction (and I still hope to be motivated by some external prod to a clear conception of what I want to give as a teacher). How else can one teach effectively & develop as a teacher though without some kind of continual reflexive self-examination.

· What are you interested in researching - people, groups, communities, documents, images, organisations?

Again all of these objects (and subjects captured through ‘ethno-methodological method and analysis) of research are important to me. The research should eventually focus on how these foci of interest interact with each other in day-to-day teaching situations in HE.

An example of small scale thinking I did on using multiple perspectives in qualitative research analysis in the language of assessment (abandoned as unworkable) is this old blog. (click to open in new window). When I look at it now it seems confused but it does at least say that what I want is some approach that integrates multiple inputs.

In the end, my interest remains speculative and reflective and this may be because I have personally ‘sort of’ resigned out of the practical issues. But the interest remains because I find ‘research’ so often used to justify a certain approach to subject matter that I can’t quite feel comfortable with. I think this is painfully evident in this blog ‘blog-blasted from the past) - (click to open in new window).

· Do you have an initial ideas for the kinds of methods that might help you to gather useful knowledge in your area of interest?

Ethnomethodology that looks from within learner and teacher communities at perceptions of the barriers and commonalities that arise in performing the identities that inscribed learner & teacher roles prescribe. How deterministic are these roles? Can they be explored in terms of performative ambivalences that threaten ‘stable’ power relations? Is that a worthwhile aim?

· What initial questions do you have about those methods? What don't you understand yet?

To the last part, there is quite a lot I don’t understand. In many ways, I will learn whether my interest is in pursuing ‘research methods’ or whether it is purely speculatively epistemological and based on the lived experience of epistemological conflict in the contemporary institution of HE.

· Do you perceive any potential challenges in your initial ideas: either practical challenges, such as gaining access to the area you want to research, or the time it might take to gather data; or conceptual challenges; such as how the method you are interested in can produce 'facts', 'truths', or 'valuable knowledge' in your chosen area?

Many. This seems the base problem for me and stymies me, at the moment, from conceptualising a research role for myself and which indeed was a barrier to me taking on an Ed.D at this time as the first step in this process.

·

What are the main points Sohm is trying to make about biographies of

Caravaggio?

· How is his case similar to or different from that of Raphael?

I have never understood the point of reading sections of a paper, especially when directed to comment upon issues related to the theme of the paper itself, although I warmly recognise that this is an attempt to lessen the learner workload and therefore has advantages. Hence, this answer is based on a quick reading of the whole paper. I do not yet know whether I will want though to confine the answer to the introduction of it. (And still don't know after finishing it thus far - as far as I want to go).

· The main points are:

o The function of achieving readable and engaging narratives elides or possibly (in the biopic) over-rides the function of biography as an objective historical account.

§ This may extend to using the narrative to make of the life, death and intervening events a meaningful pattern imposed on it by the perception of the artist’s life as a whole.

§ The art itself is seen not only as product of one single individuated ‘ life’ but also as the limiting case for the authenticity of our reading of one or more artworks (and indeed, sometimes the defining character of the artwork as a whole oeuvre.

o Kris & Kurz introduced a formal notion of the function of ‘early modern’ biography to articulate the meanings of an art work, and its place in an oeuvre, in terms of a ‘higher truth’ (449). Narrative in the form of iconic myth becomes the locus of that meaning. This is especially true of ‘death’ stories, which retrospectively shape the meanings of earlier artworks.

o If biography can shape interpretation of paintings, the corollary is also true (459). This is in past a function of the function of language to convey multiple meanings simultaneously, and this is particularly true of literary language (450). A retold life event can be treated as a form of allegoreisis.[i]

o The allegorical meanings of an artwork, read as a combination of the multimodal intertextuality of biography and work, can be the substantive evidence used to critique:

§ The artwork OR oeuvre;

§ The artist per se – including their socio-cultural emplacement in history.

§ The culture itself, which the art is used to articulate (modern or contemporary art for instance cp. Tracey Emin author-function.

o A Death Scene is the key to ultimate truths. This is the case for a number of types of biography, even those making ‘truth claims’ (451).

o The meaning attained in a review of both life can be an iconic allegory: Raphael as Christ, Michelangelo as Marsyas, and Caravaggio as Judas Iscariot (452).

o Those iconic meanings are embedded in visual art by manipulations of facial expression, properties, costume and adornment. However, from the evidence (452f.) I would also add relationship to the artist’s formal framing devices). We could include Poussin in this.

o In Caravaggio meaning, description and allegorical interpretation attach to notions of darkness, in relation to morality, nature and formal tenebrism – shadowing, chiaroscuro. This can verge to the notion of Caravaggio as anti-Christ (or anti-artist) in some particularly class-bound accounts.

o In particular it can characterise artists who supplant pursuit of the Platonic Idea for material objects in Nature. Including fleshly ones, but chiefly monetary reward or its commodification in possessions.

I would caution here that ‘allegory’ is the Renaissance (as inherited through The Neo-Platonist revival, was complex. In England, for instance, Spenser speaks of his Faerie Queene as a ‘continuous allegory or darke conceite’ (sic.). Here ‘dark’ mirrors 1 Corinthians 13 about the sublunary world as a place in which we see ‘as in glass darkly’. We can’t confront then uses of darkness in Renaissance & 17th century art as baldly as this paper does. To be ‘dark’ is to secrete one’s meaning. This does not always invalidate it – it often purports to do the opposite.

- Raphael is said to be presented as Christ. I

agree in as far as we read that identification as allegorical – a function of

meaning complication. In both cases Icarus myths are used (see Castiglione’s

faux-Raphael) to show attempts to over-reach in an assault on the Sun (like

Marsyas with Apollo, Icarus with Apollo in his natural light). Of course,

though rooted in similar meanings, they can act differently. Thus Caravaggio is

Icarus who is punished by the sun (Apollo) for too much savouring the “cellars

without too much sunlight” and for covering up ‘the difficult parts of art’. (458)

Darkness in Caravaggio is purported to allegorically point to his love of the lowly, a baseness and lack of right learning that even elevation to the Knights of Malta cannot hide (458). The underlying myth here is of the foundling (as found in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline and The Tempest for instance – very much plays about art as noble or base). Stolen from Court, the true noble will show himself so, even though ‘basely’ brought up. Likewise darkness is a space with different meanings – sinister, psychological (mad isolation), social as well as theological or philosophical. (458).

In both cases the artists are described as ‘self-fashioning (459)’ (using Greenblatt’s terminology), we cannot assume that Caravaggio fashioned a dark, demented and fragmented self-image for the reasons given by his biographers. For a modern reading, see Schama’s The Power of Art. Nevertheless both detractors and emulators accept that C self-consciously evidences the phrase, ‘every painter paints himself’. This can be used to look at not only subject-matter, and the artist’s relationship to subject-matter, but also technique – chiaroscuro of course but also naturalism and the means used to achieve stylistic individuality. Detractors speak of Caravaggio ‘driven’ by a malign or disordered psychology to ‘paint his own ugliness’. But I wonder – Caravaggio is, for me the master of the ‘dark conceit’ – the invitation to seek meaning at a number of different levels, or to speak more contemporaneously, through a number of possible conflicting discourses.

[i] Mirriam Webster definition of allegoresis: the interpretation of written, oral, or artistic expression as allegory.

…, let me start by saying that to recognize true perfection is so difficult as to be almost impossible; and this because of the way opinions vary. …. Still, I do think there is a perfection for everything, even though it may be concealed, and I think that this perfection can be determined through informed and reasoned argument. And since, as I have said, the truth is often concealed and I do not claim to be informed, …I can … only approve what seems to my limited judgement to be nearest to what is correct; and you can follow my judgement if it seems good, or keep to your own if it differs. Nor shall I argue that mine is better than yours, for not only can you think one thing and I another but I myself can think one thing at one time and something else another time. (Castiglione (1976: 53f.)

Knowing where to start can be difficult, as Castiglione’s character, the Count, admits. It is a matter of judgement. Then, isn’t everything, says the Count in the same breath. This passage, which somehow reminds me of Wittgenstein, is actually about what constitutes judgement of what is good and best in a thing, action or person. It rests on an as yet unresolved dialectic – in a sublunary world we might intuit ‘perfection’ but never know properly that it is ‘perfection’, mired between different and varying (diachronically and synchronically) ‘opinions of how such perfection be adjudged. Judgement is a slippery thing. This is Castiglione at his most playful best posing problems of judgement and authority. The Count is talking about perfection in a ‘courtier’. We are posed by opinions about what is judged to be perfection in an artist.

This task looks at 2 opinions of what constitutes an artist’s achievement.

(1) Raphael doesn’t in a sense, in a private family letter not purposed for sharing beyond that family raise the issue of perfection in the artist per se. He is concerned to show his family that he has achieved a certain status and that status (and its surrounding circumstances) have changed since they last heard of him. The change that constitutes achievement is expressed in the following series, with more than a hint in the ordering what Raphael thinks will most be adjudged success by his current audience: first, monetary wealth, then a role with status (and that adjudged by income) and then a hint of the stability of both status and income. Raphael ‘making it’ as an artist, or at least so he thinks his family will judge, is Raphael with money and promise of more to come. Of course Raphael also associates these things with ‘honour’ that is personal but also shared with the family to which he writes and the city where they live and he originated. But that ‘honour’ is quantified in money and whose value is evidenced in those quantities. Of course, this witty letter is an act of reassurance to his family and a bolster to their faith in them and their belief that he continues to think of them, despite not writing. The final joke is telling. Yes, this could be Raphael but is Raphael in the subject position of the young man who, having left home, must prove he is making good. He does not mention the aesthetic value of his art but is this because he is not thinking of it OR that he knows (in as far as he can judge) that that will not be uppermost in the minds of his audience. We need to remember that all communication will, as I think Castiglione, suggests above will take on the values of the current interaction in assessing what matters.

(2) The Subject position of the Raphael invented by Castiglione (I'll call if Faux-Raphael) is precisely a man self-conscious that judgements differ in our world and that a better judgement is hard to assess or find. Hence, Faux-Raphael says of the ‘designs’ he sends to Castiglione that they have been judged as good in themselves, but notes that judgement may in itself be compromised in quality and sincerity. This mock letter then is a much more obvious illustration of the dilemma expressed dialectically in The Courtier.

In that search for knowledge of what constitutes ‘perfection’ in art faux-Raphael seeks models in the reconstruction of buried antiquity, critical authority of a master (Vitruvius) but neither offer ‘all that I need’. What this suggests is that perfection is an aspiration rather than an achieved phenomenon and that searching it is dangerous and potentially fatal (the point of the use of the Icarus myth here – to fly too near to the sun of perfection may end by drowning in a sea of undifferentiated mutability.

This piece is full of humour about dangerous death: does, for instance, the original Italian allow you to read the joke in English that shows that the ‘collapse’ of a career can be like being buried under the weight of a falling St. Peter’s. The metaphors of falling and rising he are contiguous – collapsing like a building, raising like Icarus to show that the issue of social reputation too is a dangerous area – seeking perfection may fall foul of the fact that there are too many opinions of what perfection might be – and some of them, not that well informed (even if it be one of successive Popes, as both Raphael and Michelangelo were to find).

The meat of this passage is very playful but central to Castiglione’s philosophy (perhaps I think of him as a precursor to Wittgenstein). A perfect woman cannot be fairly judged – note how Castiglione plays (heterosexual men will be heterosexual men) on Raphael’s well known uxorious life – without being found in a wide trial amongst a very large sample of women. Just as he submits his ‘designs’ to what he supposes is the better judgement (than his own, The Poe or the Roman intelligentsia) of Castiglione at the opening of the letter, at the end, he invites Castiglione in a similar bed-hopping hunt for the ‘best’ in ‘beautiful women’. This is more than a mere joke, it dramatizes the problem in the Courtier – we believe that ‘perfection’ exists but tastes so vary that we cannot attest to perfection without trial of it. At this point, it may no longer be see-able as ‘perfection’. This is the same dilemma we find in Milton’s Comus. Perfection survives not in realised body but in an imagined one that is desired but never caught (witness Galatea in flight in her scallop shell – the scallop is the very icon of eternal perfection). It is really ‘a certain Idea that comes to my mind’. Such intuitions might though actually BE the road to Perfection. Castiglione fades into Plato or, at least, the ancient Neo-Platonic school Castiglione favoured.

Castiglione, B. (1976) (Trans Bull, G.) The Courtier London, Penguin Books.

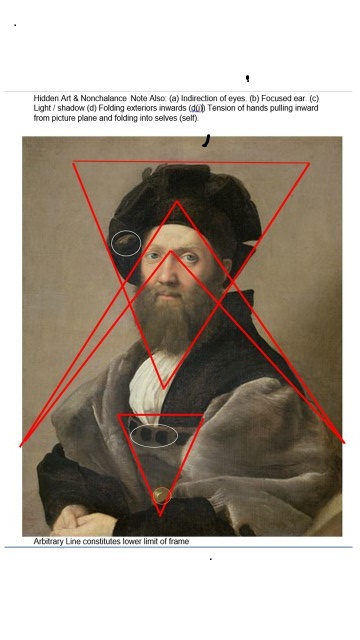

Consider Raphael’s portrait of Baldassare Castiglione in the Louvre (Figure 3.7), asking what it reveals about the sitter and artist.

· How is the portrait composed?

· How would you describe the relationship between sitter, artist and spectator that it sets up?

I have attempted in the Figure above to use rough geometric shapes to describe the composition and suggest the almost axial centrality of the central figure and the distribution within that figure of the volumes suggested. I have described it as almost like a set of notional triangles that work in interaction to focus the face of the sitter, and render it the compelling focus of a viewer’s attention.

This attention I do not equate with that of the artist since the latter employs a number of devices that get noticed in the picture only as a function of time and attentive looking. Whilst a viewer first notices the humanity of the central figure in its face and latterly hands (almost occluded by the apparent arbitrary placement of the bottom marginal line of the whole). We definitely start with the face. This is in part because that feature (or set of features seems almost islanded in volumes of clothes stuffs, whose size is emphasised and forms the width of the picture frame as a whole.

Colour is important here. The choice of soft dark colours which animate merely by being folded in ways that distribute light as the main source of their tonal variation. Colour in the face contrasts pallor with effects that appear to emerge from within the figure to interact with light – the blush like central colouration of the centre face reflected in those prominent lips.

Yet Raphael does not centre Castiglione on the picture plane itself. The torque of his body, twisted so his right side moves beyond the picture plane and leaves an important gap of space on the left (viewer’s left) of the picture. That emphasis on space creates the sense of necessary distance that modifies our human closeness to this man. It is as if Raphael reserves him slightly for himself by this compositional device. Likewise the torque of the body emerges, as viewers concentrate on that ideally placed eye level as a means of showing Castiglione’s eyes as fundamentally indirect in their imagined attention. While the iris has moved to retain an appearance of centrality (given the turn of the body), the pupil focuses above rather than on the viewer. The sitter seems both to see you and not see you.

Moreover, the embodied turn emphasises one ear, such that Castiglione is seen as both a person who sees and hears – as himself attentive (as someone who takes in the world rather than projects himself into the world. This is emphasised to me too by those reticent hands. Raphael composes the picture so that they just appear above some arbitrary line, as if caught by accident. How different from earlier Renaissance uses of a balcony to emphasise the resting place of hands. These hands are tense and enfolded, appearing to move into themselves. To me they imply a tension moving against and into the body of the man, again emphasising interiority – areas of something unknown and hence forever distant from the viewer.

This enfolding is mirrored in the clothing, which although asserting boldly (if also in a muted fashion) colour, volume, decoration and both social & financial value emphasise the recesses of shadow and a folding in of light to a darker interior. Castiglione’s outline is less prominent against the shadowed background to our right.

Castiglione is clearly a man who both values art and manifests that value in the hidden features of that costume, otherwise made beautiful by light. The gem on his hat mirrors the expressive and open shape of its highs and resides (unobtrusively just above them). Likewise the woven refinements of his garments almost hide – that gold button, the line of woven patterns above them in the base of the inverted triangle the button proposes, and the apex of the triangle in the woven insignia at the centre of his headpiece. This is most reticent – beauty and taste shown nonchalantly (Bull’s translation of Castiglione’s (1976:67) term sprezzatura) _ Wikipedia opens in new window (use with caution).

I have discovered a universal rule which seems to apply more than any other in all human actions or words: namely, to steer away from affectation at all costs, as if it were a rough and dangerous reef, and (to use a novel word for it) to practise in all things a certain nonchalance which conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless. … So we can truthfully say that true art is what does not seem to be art: and the most important thing is to conceal it …

I would say that this is precisely about the relationship between Castiglione, Raphael and his viewers. What we see conceals the art of both men only to blazon that art more in the paintings (and the philosopher’s) deeper, richer truer and well-educated art. In fact I would say the picture constructs art as riches – praises the luxury of the prince and entourage whilst it decries and vulgar show of that richness. However, show there must be or there would be no art alone.

Sitter and artist display not only exterior but interior riches (those of deep character so loved of the period). The viewer will see these if they can from a distance as an admirer but not as an equal

That’s about as much as I can think of – now to the revealed discussion.

All the best

Steve

Consider the self-portrait

of Raphael (Figure 3.6). What does it reveal about the artist’s identity? What

is the relationship between Raphael and the other sitter, and what does it seem

to tell us about Raphael’s persona? Note that the second sitter’s identity is

not known, despite much speculation by art historians.

‘acheiropoieton’, an image made ‘without human hands’. : The look and hands of Raphael

This may turn into a small essay. Why? Because I desperately want to resist the idea that Raphael paints himself as Christ. In as far as he is like Christ, I believe the simile is merely and self-consciously rhetorical and communicates complexly. This is very much a ‘thing’ of mine, perhaps an obsession and, in this sense, this can never aim to be an essay in miniature. However, I do not see any identification with Christ as necessitated in this or other self-portraits of Raphael. If it is there at all, it is only in terms of an analogical allegory of Christ’s mission (the way, the truth and the life) in that of the artist. Concentration on the facial appearance seems to me less important (although possibly there I admit) since there is no pressure – in our portrait - on the characterisation of Christ as ‘type’; even if a humanist type such as is explored rather thinly by Thomas (1979) and more deeply in Kemp’s (2012:35ff.) treatment of Leonardo’s portrait of the saviour.

Nevertheless the lively debate in Christian thinking on the nature of images of the divine is important. It matters that the ‘Veronica’ (as Dante calls it) is the imprint of the real body of Christ precisely because it both (a) differentiates the image of Christ from a ‘graven image’ & (b) takes away the impurity implied by the fact that the divine might need human ‘hands’ to represent itself as an idea. However, the relationship between Raphael and his ‘friend’ here is clearly mediated in terms of what we see in the hands of the two participants. Raphael’s hand sits at rest on his friend’s shoulder in total relaxation from labour (manual labour characteristically) whilst the friend’s hand works to express intention and purposive meaning. If feels to me to point in the index out of the picture plane – a point that is essential to readings of this picture I’ve encountered. And the friend’s hand co-operates with his head and face, one attempting to direct, in its backward glance, the gaze of Raphael towards that place where he wants it to be.

That both hand and face can be read together as index of interaction and intentionality (or its lack) is common in Raphael I think. The very opposite being the sketch of ‘A battle of nudes (The Siege of Perugia)’ where hands and gaze express committed action and mental intention in total concord, creating a directed flow in the viewer’s gaze on them towards the right edge of that drawing (NGS 1994, Item 19 - not pictured).

There is as a result of the focus towards

dramatic action in the latter a great stress on human body and art that is of

the body. In contrast, all of Raphael’s known (or suspected) portraits (Thoenes

2016, 7ff) show Raphael as merely a head without active hands. The gaze of that

head is never on the action of the picture but towards the viewer, implying a

relationship of minds engaged in looking (and thus valorising looking as an

act) rather than an active physical or even mortal relationship. This was

perhaps noticed by Raimondi as noticed both by Thoenes above and Whistler

(2017) in her essay on the importance of ‘hands’ in Raphael. For me it is the

relationship between head and hand that is important here. That is because desegno in Vasari and others was both a

matter of what happens in an artist’s head when s(he) plans and their hands

when they draw. Yet there is something less than perfect, less than

ideationally divine. About the reliance on manual labour. It is for this reason

that Raphael appoints himself as of the gaze and the head (looking out to an

unperceived and therefore potentially eternal viewer) rather than to any other

mere actor on or behind the picture plane. We see this in our picture but also

in the School of Athens.

There is as a result of the focus towards

dramatic action in the latter a great stress on human body and art that is of

the body. In contrast, all of Raphael’s known (or suspected) portraits (Thoenes

2016, 7ff) show Raphael as merely a head without active hands. The gaze of that

head is never on the action of the picture but towards the viewer, implying a

relationship of minds engaged in looking (and thus valorising looking as an

act) rather than an active physical or even mortal relationship. This was

perhaps noticed by Raimondi as noticed both by Thoenes above and Whistler

(2017) in her essay on the importance of ‘hands’ in Raphael. For me it is the

relationship between head and hand that is important here. That is because desegno in Vasari and others was both a

matter of what happens in an artist’s head when s(he) plans and their hands

when they draw. Yet there is something less than perfect, less than

ideationally divine. About the reliance on manual labour. It is for this reason

that Raphael appoints himself as of the gaze and the head (looking out to an

unperceived and therefore potentially eternal viewer) rather than to any other

mere actor on or behind the picture plane. We see this in our picture but also

in the School of Athens.

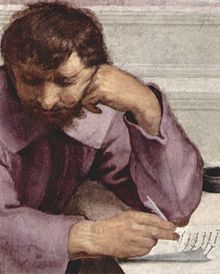

In the detail above Sodoma is veiled and darkened by his attention to other artists, whilst the light on Raphael’s face emphasises a gaze that goes beyond Sodoma or Pinturicchio to us – his repeating viewers and requests a meeting of minds. And not because he is isolated (spiritually at least) here. Look at the figure left who Goffen (2002:222) insists is both Michelangelesque and perhaps Michelangelo himself, whose gaze is obscured and shadowed, with his hand in restless action.

The same is true of the ‘The Expulsion of Heliodorus’, (Theones 2016:10 - not pictured) where Raphael bears a weight but concentrates attention on the gaze as if the work of the hand were as nothing, and the disputed Uffizi self-portrait (not pictured).

Now this has something to do

with divinity but it also has relation to the relative importance of manual

dexterity and work compared to the role of the head – in design / desegno.

Raphael is building a characterisation of the artist I’m arguing that might use ‘godhead’ as one of its analogies but not merely in terms of appearance. The Godhead is more impressive when it plans than it executes (as for living our assistants can do this for us). Although Raphael is not a mere aristocrat as that analogy with the Duchess of Windsor suggests. He values the products of his hand and the action of hands (perhaps in interaction they are genuinely potentially one – hence the beauty of the painting).

Look for instance at the telling drawing of unconnected (if that ever can be true) of apostolic head and hands in Catalogue item 120 (Whistler & Thomas 2017: 246f.) In our beautiful painting of two men, the gaze which looks out and beyond mere relationship in real time is valued in relationship to that which acts out of the picture. Here there may be a Christ analogy. No-one can ever know what it is that is pointed towards. It could be the artist’s mirror or a third person who WAS there. Belting (2013; 133ff) argues that the two point to the picture from whose completion Raphael and sitter are resting and showing by the compared attitudes and appearances the difference between how art might and must capture social masks but also the living face in the moment of the ‘speech act’. But much must be assumed in this reading. But then that is the case in any reading. That is why I think Raphael inevitably engages us as viewers, asking for his picture’s completion in that relationship of ideas. Now a Christ analogy might be useful here. Raphael’s mission to his friend may be like that of Christ – to ask his disciple or mentee to see the ‘way, the truth and the life’ he must lead – with all the pain therein. However, I see that as one of many possibilities. The painting’s meaning for me is overdetermined by Raphael’s mentation within of the meaning of art for the true artist, where immortality and divinity appear in a more mortal light – all in war with time (a true Renaissance theme and in Edmund Spenser as much as Raphael).

References

Belting, H. (2013) Face and Mask Princeton & Oxford, Princeton University Press.

Goffen, R. (2002) Renaissance Rivals New Haven and London, Yale University Press

Kemp, M. (2012) Christ to Coke Oxford, Oxford University Press

NGS (National Galleries of Scotland) (1994) Raphael: In Search of Perfection Edinburgh, NGS.

Thoenes, C. (2016) Raphael Cologne, Taschen.

Thomas, D. (1979) The Face of Christ London, Hamlyn

Whistler, C. (2017) ‘Raphael’s Hands’ in Whistler, C. & Thomas, B. (eds.) Raphael: The Drawings Oxford, Ashmolean Museum Oxford University.

Whistler, C. & Thomas, B. (eds.) (2017) Raphael: The Drawings Oxford, Ashmolean Museum Oxford University.

Consider the common

themes in the Vasari extracts and the 4 descriptions from contemporary writing.

I have extended this task to include Vasari because I thought that would help me more. I find the task as set rather leading since it presumes the identity as Christ that might be being built around Raphael’s person in all the accounts, although I have yet to read the discussion. Having read them again and again, I do not find clear evidence of such an identification in the 4 accounts exactly contemporary to the death, other than might be prefigured in the notion of Christ as the new Adam (as humanity transfigured by His redemptive function).

In Vasari however there seems to be a daring identification of Raphael as an exemplum of ‘possessors of rare and numerous gifts’ as one of the ‘mortal gods’. Hedged around with the signs that this might be blasphemous since Christ is as near as Christianity gets to a ‘mortal god’ (a god that can die), we still have to remember that Vasari cannot be evoking Christ as such because Christ is not one of many ‘mortal gods’ in Christianity. And then the extract offered leaves out the sentence qualifying the possible blasphemy. That continuation makes it clear that the immortality secured by Raphael (and his like) is because of the endurable remnants of himself that he (and they) have left on earth as support to his ‘honoured name’. Is it not possible then that this discourse is not about the artist as immortal but the endurance through time of his works (including Art)? I think such an interpretation possible, even in Vasari.

Of course Vasari makes this clear in his account of the Transfiguration. Our translation calls this picture ‘divine’ but both the Penguin and Oxford Classics translation prefer ‘inspired’ for this term. We need the Renaissance Italian, but even then we might fail to understand the nuance of the term, so distant is that version of it from even contemporary Italian. I am pretty certain however, that though Raphael may be said to be like Christ, he is not identified with Him but is instead shown to be enduring because he raises Art to the level of the comprehension of the divine and the godly in the Christian Trinity:

‘with His arms outstretched and His head raised, appears to reveal the Divine essence and nature of all the Three Persons united and concentrated in Himself by the perfect art of Raffaelo, …’

The role of Art here is to ally itself with Godhead. It is not the role of Raphael. That, at least, would be my reading. I think this is evident too in Castiglione’s account of Raphael who insists that Raphael is not merely a great artist or is so only because he facilitates a revelation of what Art can and ought to be doing (Castiglione / Bull 1976: 98f.).

To be clear about the consequences of this, the treatment of death (the sure sign of mortality) in a ‘Life’ story is clearly crucial. I think Vasari makes it clear that Raphael is not the new but the old Adam – a man who chooses violent excess and secrecy in his sexual life is not Christ. He fears even to admit his own humanity – a very UnChristlike thing – until he must confess in his last office. He is a ‘good Christian’ at the end but not Christ and he dies as a Christian must, without, at and up to this time, rebirth. However he pays witness to the reborn Christ through his ‘perfect Art’ as we have seen. His soul’s immortality in heaven is at the end compared not with his person but with that with which ‘he embellished the world’.

Although this may seem like nit-picking, I think it important that the myth of Raphael’s perfection is seen not, by his contemporaries, as like Christ but in using himself and his art in that service. Too like mortal men who only act properly when they know how to act, Raphael’s secrecy and excess (however much Vasari admires that) was the source of his death, which proves him mortal, whilst allowing art the chance still of immortality – enduringness beyond death. Remember that Vasari does not see redemption of sin in Raphael’s story but only the ability of art to ‘efface any vice, however hideous, and any blot, were it ever so great.’ That claim does not elevate Raphael into the superhuman but rather forgives him for his humanity.

So, if we turn to the very contemporary accounts, I find little that makes him Christ-like. I sneaked a peek at the account that follows this exercise and find nothing in this extract from Lippomani (10 April) that justifies the construction of the extrapolation – ‘as if God planned it this way’. Maybe the justification for this reading is in the hidden discussion. I’ll see. There is the potential of seeing Raphael as Christ in Pico’s (7 April) letter that states without doubt that ‘ The heavens sent warning’, but even then we may not be reading the tone of this statement correctly. After all, Pico, a courtier, is writing (with ‘wit’ – which means with the use of rhetorical figures - as the Renaissance courtier must) to the Duchess herself. Both would use language that emphasises and elevates art. What our lives Raphael is not a reborn self but a ‘second life’ that is equated with Fame. I think Sir Walter Raleigh would have known how to read this – is it formal hyperbole – in ways we do not.

As for the worldly Michiel (6 April) in private to his diary he notes only the importance of Raphael in terms of his wealth and his scholarship (without even mentioning his Art). He laments his unfinished scholarly tome on Rome rather than the promise of future Art. Of course, by the 11 April and writing to a fellow courtier, he has heard the rumour (he says it as that) of the heaven-sent warnings but makes sure we understand that these may really be more to do with ‘the weight of the porticoes on the door’ – again with great weight. What will immortalise Raphael, as Castiglione, would have understood is the transfiguration of his reputation into art – ‘moving and perpetual compositions’ says he wittily and perhaps not a little sarcastically (possibly).

So my account does not seem what is prefigured for me in this task but I’ll now see by looking at the hidden discussion.

One issue with these accounts of course that Raphael is said variously in them to die at the age of 33, 34 & (in Vasari) 37. In a numerological age, fixing on one might be important for establishing a commonly held myth.

All then best

Steve

I love to answer these and commit to an answer before I

reveal the course discussion, so here goes again:

. While reading, you should ask yourself:

· What does Butt claim about gender and sexuality in this essay?

· How does he characterise the sexuality of Rivers?

· How does he find this sensibility in Rivers’s artworks?

· What does this suggest about gendered identity?

Note: What Did I Do? is the title of Rivers’s autobiography from 1992

1. I find this essay somewhat confusing and I would not wish to say that Butt commits to straightforward and univocal characterisations of either gender or sexuality. He appears to wish to characterise a socio-culturally determined set of subject positions and a discourse associated with those positions that in 1940s and 50s USA characterised a marginalised community and how those positions became equated with a statement of an artist’s wish to confront and challenge the norms of society. In a sense they seem to offer merely a means of characterising art and artist as denying any solidity to the objects it reproduces and produces and as, therefore both object and subject, understood both in terms of the ‘object’ represented and the subjects who both respond to culture through remaking its imagery.

Yet it is not so simple, since, Rivers also uses those subject to both play and enact sexual practices that those subject positions enable in a minority and oppressed community: the sexualisation of the male body as object of desire and appropriation, the valorisation of the penis and the deconstruction of masculine heterosexual hegemony over the realm of desire.

Problematically, the discourse of gay

subjectivity already employs subject positions which both critique but also maintain

the validity of binary gender discriminations, which can be experienced as

oppressive by lesbians, some gay males and some women. Thus the issue of ‘gay

subjectivity’ is far from simple. The ‘self-othering game’ (p. 89) may enact

otherness in complex interacting forms that may undermine them. However, in as

much as it remains play or game, it refuses to challenge essentialist notions

of subjectivity that may be the real root of contradiction in subjects seen by

themselves and others. Butt seems want to point out that Rivers preserves

essentialist positions ('real' heterosexuals act out as gay and vice versa).

The same might be said of the use of feminine subject positions – not only in

painting but the art of Tennessee Williams – which retain some of non-playful

power dynamics which contradistinguish binary power distictions like male &

female.

I may not have read carefully enough but I am

unsure where Butt stands (or sits to carry on the camp play) on this issue.

2. Butt characterises Rivers as playing gay but also benefitting from that play by the appropriation of sexual pleasure possible when the sexual subject which is the other is hardened into sex object. He could be clearer about this if that is what he means. Tennessee Williams, for instance, shows that the appropriation of the sexual object through performance is both dangerous and a matter of real power – in Both Streetcar Named Desire and, my favourite, Suddenly Last Summer. He also suggests that Rivers uses sexuality and sexual pose as a means of characterising the challenge to conventional meaning posed by art and the artist. Images no longer mean what the prevailing power structures in society want them to mean and are therefore ‘queered’ by the legitimation of counter-cultural meanings.

3. I am not sure that we are really looking for a reflection or mimetic representation of River’s own sexuality in these paintings but rather a performance of traditional subjects – both in the act of the painting and the representation of these subjects’ action. I’m quite happy to take on the reading Butt gives to the painting of the figure of Washington in the boat (see above). The emphasis on the stark outline of the naked leg and the phallus is taken as an enactment of painterly emphasis but also as an action in Washington that offers his sexualised body for some sort of appropriation.

However, I can’t stop where Butt

does at camp fun. There is an abstraction in the use of white here (and

potentially in the brushwork mentioned but I can’t see that) that does other

than point out the joke of Washington’s ‘burgeoning basket’. Looked at in the

context of the whole picture, that white patch is recalled in figure of

Washington before embarkation (below) for instance as well as other abstractly

white motifs. There is something of glory in Washington’s horse that defies

outlined drawing. Now, this might be merely making an equivalence between

stallion between the legs as phallus – the white makes his neck look like a

phallic projection and it, as in the Washington in the boat, reflected by the

horse’s strong white and painterly legs.

But return to the whole painting and we see a display of such stark whites throughout, not least in the characterisation of the water. These whites may or may not have meaning but they cannot be confined to a camp joke. I may therefore be wanting to see ‘more’ in the picture than a camp joke. I agree that in the 1950s camp and gay life seemed to heterosexual men to embody excess (p. 84) but the ‘excess’ in the white of this picture cannot be reduced to such stereotypical characterisations. It may have multiple meanings, not least in re-characterising light and notions of illumination and reflection. In a sense, it stops Washington being the iconic focus of the picture, replacing that figure by homage to spaces and spatial relations in time and space. At least I think it does.