Edward Hallett Carr (1892-1982) was first a diplomat and then a historian, most notably of the Soviet Union. He has been described as left-leaning, Arthur Marwick categorises his history as 'Marxist'.

Edward Hallett Carr (1892-1982) was first a diplomat and then a historian, most notably of the Soviet Union. He has been described as left-leaning, Arthur Marwick categorises his history as 'Marxist'.

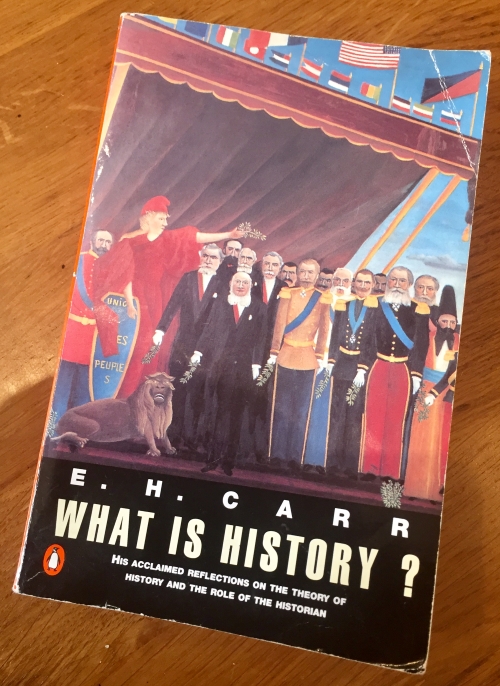

In January-March 1961, whilst a Fellow of Trinity College Cambridge, he gave the G.M.Trevelyan Lecture Series of six lectures - these were subsequently published in book form as What is History? later that year. I've read the second edition, which was first published in 1987, this contains a preface that Carr had written for a second edition, and some notes that existed for a revision that was not completed.

These notes try and summarise and reflect on some of the key points he raises in his six lectures.

1. The Historian and his facts

Inevitably the first point has to be that historians are exclusively masculine throughout the book - a reflection no doubt of the make-up of the profession at that time and of social norms, but also Carr seems largely disinterested in any issues of gender.

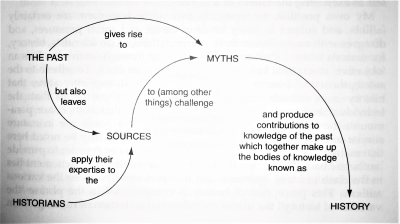

He questions what distinguishes ‘historical’ facts from everything else in the recorded past and presents the idea of 'selection' as central to the work of the historian. Carr decries what he sees as a fetishism of both facts and archives, he sees such an approach as core to 19thC history, but now outdated. He is unconvinced by what he describes as 'empirical' approaches that collate 'facts' and anticipate that history will flow from them. Carr argues that empiricism was valued above theory in the 19thC as this was a ‘comfortable’ and successful time in Western Empires, everything observed just confirmed the accepted order. When 20thC chaos starts to break out, historians were having to start thinking about bigger questions of historical philosophy.

He gives an excellent example of how selection operates using the records of Gustav Stresemann (German Foreign Minister and Chancellor). The editor who first compiled and published his records retained more which related to his 'western' diplomacy, which was seen as highly successful, and less from his 'eastern' activities - which were not. This collection was further abbreviated when translated to English. When the National Socialists came into power they destroyed much of the primary material, but fortunately copies were retained and it was possible to subsequently the establish how selection had previously operated. Carr points out the biases that would have been present if all primary records had been lost, and historian could only rely on the English translated material. He ends with the final reflection that Stresemann was his own first editor, and that the German primary records chiefly capture what he said and thought in any meetings, whilst the voices of others are less distinct. Carr argues that selection is inevitable in history.

When discussing the influence of the contemporary on views of the past Carr highlights writing by Benedetto Croce ('seeing the past through the eyes of the present') and R.G. Collingwood ('facts refracted through the mind of the recorder').

The writing and opinions of multiple 19th and 20thC historians are touched on and Carr emphasises that the reader of a history book's ‘...first concern should be not with the facts which it contains but with the historian who wrote it.’

The chapter ends with a section on the iterative process of creating history, a circling round of reading and writing in which the historian moulds facts to interpretation and moulds interpretation to facts. However, for me, he fails to be clear about when this process concludes and what indicates a settled account. It concludes with the classic quote that history is ‘an unending dialogue between the present and the past’. There is no doubt plenty to think about in the way in which such an abstract conversation could ever occur - and the spurious agency it gives to both 'present' and 'past'.

2. Society and the Individual

Carr seeks (at some length!) to establish that you can’t separate an individual from their society, ‘The cult of individualism is one of the most pervasive of modern historical myths’. He quotes Burckhardt, to suggest that individualism comes out of the Renaissance, before which people saw themselves as group members. Carr doesn’t disagree with this hypothesis, but sees this as a social process, one of ‘advancing civilization’.

Returning to his points about understanding historians, he talks about needing to understand a historian in their historical and social context, both their ‘standpoint’ and that their position is rooted in a social and historical background.

Carr surmises that the historian ‘most conscious of his own situation

is also more capable of transcending it’.

When considering the role of 'great' (or 'infamous') individuals Carr points out 'all effective movements have few leaders and a multitude of followers’ and that both are essential to their success.

Further expanding his original argument Carr says history is 'a dialogue between present and past societies.'

3. History, science and morality

At the end of the 18thC Carr sees a desire for a ‘social science’, a science of human society to which history contributed. He quotes J.B. Bury declaring history is ‘a science, no more and no less.’

Whilst appreciating that there had been a marked reaction against this view, Carr argues that science was now (1961) getting more like history. He claims scientists have largely abandoned a search for ‘Laws’ that govern and now seek ‘how things work’. He claims that history, like science, proposes and tests hypotheses - but he is silent on how these are in fact tested in history.

The chapter largely concerns itself with debunking what Carr says are reasons given why history is not a science. There are no sources given for who or where such claims are made and I can personally see other and possibly stronger arguments.

- History deals with unique circumstances, science with generality

- History teaches no lessons

- History is unable to predict

- History is necessarily subjective, since man is observing himself

- History unlike science involves religion and morality

Carr's main points are:

History deals with unique circumstances, science with generality - he simply says that historians generalise all the time.

History teaches no lessons - he claims this also isn't true, the ‘function of history is to promote a profounder understanding of both past and present through the interrelation between them

History is unable to predict - suggesting that science ‘does not claim to predict what will happen in concrete circumstances' (which I think can be contested) he argues history is not fundamentally dissimilar, although accepts that the predictions may be less precise.

History is necessarily subjective, since man is observing himself - I found the argumentation complex here, Carr basically seems to argue that 'classical' distinctions between an observing subject and observed object have now broken down and new forms of philosophical thinking are required.

History unlike science involves religion and morality - Carr talks at length about morality, he argues that historians can’t make moral judgements on individuals in past, but then implies they can and should do this for events/practices etc. - I'm not clear how he justifies this distinction. He makes what seems a good point about how supposedly ‘absolute extra-historical values’ are actually rooted in history.

He suggests that those who want history not to be a science are following an outdated distinction in which:

- Humanities are knowledge for the ruling classes

- Science is for the technicians who serve them

Carr believes history and science fundamentally seek similar ends: ‘to increase man’s understanding of, and mastery over, his environment

4. Causation in history

Carr states simply that, ‘the study of history is a study of causes’ and then goes on to identify what he sees as some particular features of 'historical' causes:

Historians:

- Assign several causes to the same event

- Establish a hierarchy of causes – looking towards ‘the cause of all causes’

Carr sees historians as simultaneously widening and attempting to simplify their explanation, ‘the historian must work through the simplification, as well as through the multiplication, of causes’ he doesn't however. to my mind. explain why the latter is necessary.

He picks up two arguments (straw men?) which he says are used to undermine discussion of causation in history:

- Determinism in History - which he relates to, then, contemporary articles by Karl Popper and Isiah Berlin

- Chance or 'Cleopatra’s Nose' (i.e. Antony loses at Actium because Cleopatra is so beautiful)

I’m not sure I agree with Carr’s take on Popper’s ‘historicism’ – but clearly this term was not well defined by Popper. Carr seems to think that Popper rejects events having 'causes' whilst I always thought Popper’s concern was with the idea of a purported set of forces that drove history to a *specific* determined end; the following quote is from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Popper page,

'Historicism he identified as the belief that history develops inexorably and necessarily according to certain principles or rules towards a determinate end'

Carr’s argument is mainly that events have causes and that outcomes aren’t ever ‘free’, which he sees as Popper's contention – however he mainly argues with Berlin’s addition of the need for a recognition of individual ‘free will’ and responsibility. Carr argues that you can be a determinist and still allow for moral judgements of individuals choices.

The role of chance is something Carr accepts, but makes the argument that, as it can’t be given any meaning, it can essentially be ignored in the historian's search for ‘meaningful’ causes.

Returning to his view that history is selection, the historian will select relevant causes and discard the irrelevant (like Cleopatra's attractiveness).

The chapter ends with what feels like another key idea for Carr, that the historian works with an ‘end in view’, that they reason towards that end with reference to personal values. I think this means he believes that the actions of the historian are purposeful, that their search for meaning is in the cause of something - presumably that something varies between individuals.

5. History as progress

Carr wants to avoid history either trending towards theology and an ahistorical final end or a 'cynicism' in which history is entirely relative or a litter of inconsequential meanings. He says that concerns that a society is in decline may miss the fact that another society is progressing. As it says this chapter talks about 'progress', but I find some of the arguments obtuse and nebulous - evolution for example is seen as progress when I would consider it adaptation - sometimes Carr's 'progress' could simply be 'change'.

Carr makes some complex points about a view of the future being central to an understanding of the past. I've found this set of ideas difficult to grasp, I'm unsure whether these are views of desired futures or ways of saying that the historian looks for processes that have future consequences. One route in may be to follow up on his quote from Lewis Namier which Carr references ‘imagine the past, remember the future’ (cryptic to say the least 🙂) I think this may mean that historical views of the past are created in response to thoughts about the future, but perhaps a reading of its origin Conflicts: studies in contemporary history (1942) will help!

Carr forms a definition of the 'objective' historian from this argument:

They...

- rise above the limited vision of their own situation in society and history

- project their vision into the future to give more lasting insight into the past

Sticking with his initial coinage we get to history being 'a dialogue between events of the past and progressively emerging future ends.'

He questions whether future success is the correct criteria of historical significance, accepting that history is generally not a record of what people failed to do. However, what it was that they 'did' may become clearer over time. He suggests that if you consider the life and actions of Bismarck then across time from 1880 to (a then future) 2000 it is likely there will be an increase in the objective judgement by historians - but doesn't make it clear to me on quite what basis he makes this assessment, other than more possible implications being apparent.

Carr says historians strive for a ‘coherent relation between past and future’ which rings true and talks about how past facts and current values interact, reiterating that values have a history too.

Whilst I'm not convinced that 'objectivity' is ever given an entirely clear meaning, Carr ends by saying that the 'objective historian' is one who 'penetrates the interdependence of facts and values'.

6.

The widening horizon

In his final chapter Carr makes some (as far as I'm concerned) rather contentious claims about the direction the future will take, but there are still interesting points along the way.

‘History is a constantly moving process, with the historian moving with it.'

Carr talks about dramatic changes in the 20thC, changes in 'depth' and 'geography'. People are now ‘self-conscious’, aware of inner as well as outer influences and may now 'transform themselves' as well as the world.

He sees these times as an age when there has been an 'Expansion of Reason' – bringing new groups into the 'realm of history'. There is a deeply problematic argument here about how those apparently excluded in the past are only now coming into real, 'historical' being - presumably the poor, women, non-European people? I'm not sure this stands up to much scrutiny really.

His discussion of a 'new geography' are directed towards the East in particular and come across as quite prescient. He says in conclusion that people shouldn't be insular and argues for taking on bold fundamental challenges not engaging in the 'piecemeal social engineering' that Popper has advocated (never the most inspiring of phrases!). Carr says he worries that he encounters a fear of change – but that change is happening whatever anyone thinks - his final quote is the one attributed to Galileo ‘and yet it moves’.

Some final thoughts:

Like many 'classics' this book is not quite as enlightening or startling as you might hope. I came away unsure if Carr had a completely coherent argument, he certainly misrepresents 'science' and I also felt he fudged some ideas around empiricism and objectivity. Perhaps this is mainly a corrective against 'let the facts speak for themselves' and an encouragement for reflexivity in historical reading and writing?

Here are a few more Carr-related links

Reviews in History (a review of What is History? by 'post-modern' historian Alun Munslow)