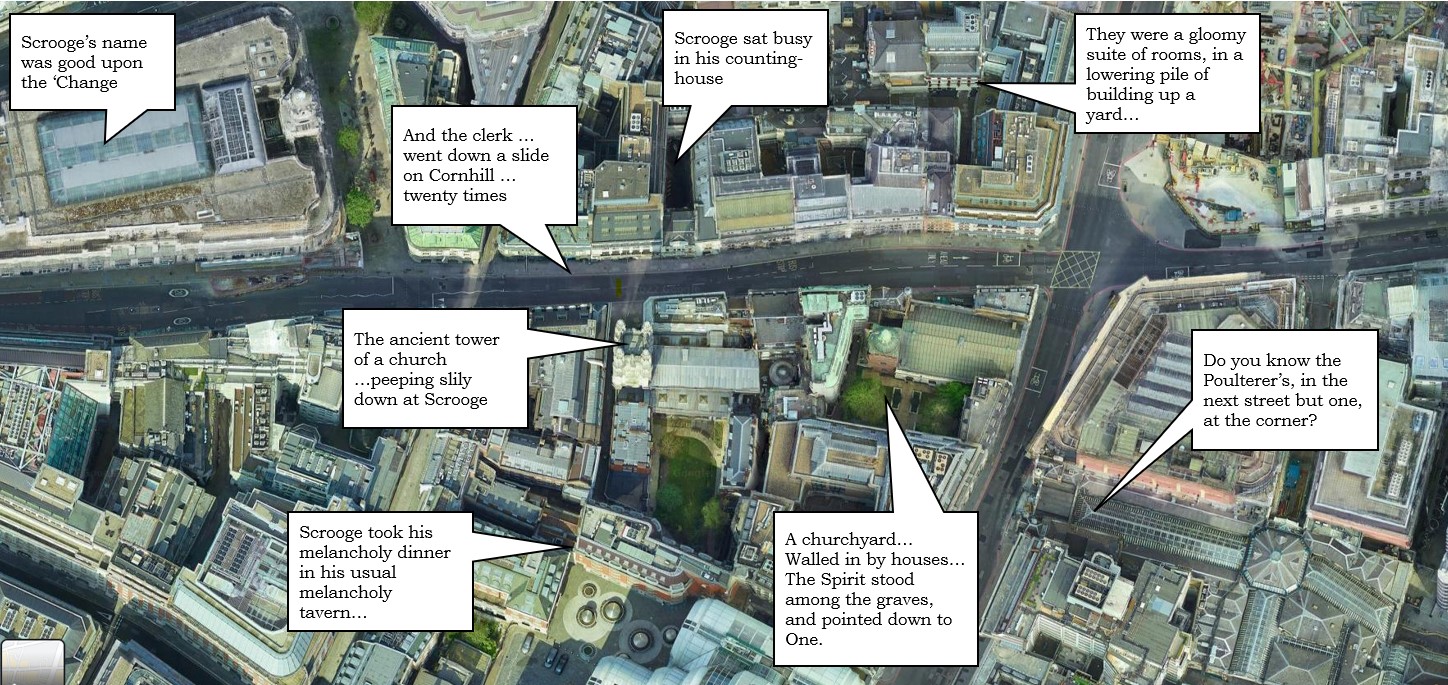

A frosty trip across to Yorkshire Sculpture Park today, followed by a visit to the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds.

I'd gone to YSP to look specifically at the exhibition 'Relics in the Landscape' by the contemporary American sculptor and artist Daniel Arsham, as an example of his work is included in the TMA on Greek and Roman Sculpture. There are six pieces, all displayed in the Formal Garden which is (as it implies) a formal green space, overlooked by a balustraded viewing path. Each sculpture is cast in bronze and coloured to simulate the patina seen on a classical statue. All the sculptures are modelled on existing iconic objects either classical sculptures or 'pop icons' like Pikachu or the bicycle from the film E.T.. Sometimes the scale is increased, and each sculpture is also marked by areas of what the artist calls 'erosions' as though they have been eaten away in some process of decay. Within the erosions are geode-like 'crystals' cast in stainless steel, the combination 'suggesting growth, transformation and the persistence of time'. Most of the statues are based on a plinth of some form, but the dominant sculpture 'Unearthed Bronze Eroded Melpomene' is designed to appear as though parts of the sculpture may yet to be excavated from the ground.

Unearthed Bronze Eroded Melpomene

This is based on a statue dated from c. 50 BCE of Melpomene, in Greek mythology the muse of tragedy and lyre playing. The original sculpture is now held in the Louvre Museum. Arsham has dramatically scaled up the head from the original statue.

Bronze Eroded Venus of Arles

This is also based on a statue now held in the Louvre Museum, Vénus d'Arles thought to have been created in the 1st century BCE.

Bronze Eroded Astronaut and Bronze Crystalised Pikachu

Whilst the massive bronzes in particular had a dramatic impact and were beautifully set in the landscape I was left a little 'underwhelmed' by the works. The patchy erosions, didn't seem to me to really give quite the idea of a transforming process that may have been intended - perhaps that was because the 'crystals' were cast objects, images I've seen of Arsham's work for interior display use 'actual' crystals and I think look more intriguing. We're used to seeing classical statuary in various stages of decay, so for me it would have to be the 'change' that could bring some excitement.

The idea of Pikachu as a latter-day Ozymandias didn't really grab me 😂

After some packed lunch and a lovely bowl of soup at YSP I headed home via Leeds, and dropped in to see the exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute 'The Colour of Anxiety'

This was a great, three room exhibition of sculpture from the Victorian period, but with lots of really direct links to A111 and to the development and questioning of tradition.

The full title of the exhibition was 'The Colour of Anxiety: Race, Sexuality and Disorder in Victorian Sculpture' and the key to all the exhibits was a reflection on the move 'away from the the whiteness of Neoclassical marble' by British sculptors in the second half of the nineteenth century - and the inclusion of colour in their work.

There were links in this movement to the 'Gothic Revival' which we will look at later in the course, with interests in medieval art techniques, the rediscovery of ancient polychromy in sculpture, 'Orientalism' and new industrial techniques. The exhibition encourages us to also think about the impact of ideas of societal degeneration, Darwinism', race and imperialism and changing sexual politics.

'From the Hope Venus to the Tinted Venus'

Sculptures in this room included Antonio Canova's Venus (a representation of the Neoclassical ideal) and Hiram Powers's The Greek Slave which essentially has Venus in chains, representing a Christian white slave in a Turkish market, but perhaps indirectly talking of American slavery (Powers was American) - but also emphasising (like a number of the works here) naked bondage.

There was book on display by Antoine-Chrystome Quatremère de Quincy who apparently coined the term 'polychromy', challenging beliefs that ancient Greek sculpture was never coloured.

There was also a preparatory model for a 'Tinted Venus', by John Gibson that went on show in 1862 with 'ivory-tinted skin, blue eyes and rosy lips.' It apparently went down a storm with the public - but outraged artists and critics.

Finally, of relevance to A111 there was a 'table-top' sculpture of Cleopatra Dying, by Henri Baron de Triqueti, which was made from ivory and bronze (known as chryselephantine sculpture) on a marble and ebony base. This was seen as meeting a 'growing taste for coloured materials but also a fascination for all things Egyptian.'

Antonio Canova Venus (The Hope Venus) 1817-20

Antoine-Chrystome Quatremère de Quincy Minerve Du Parthenon from Le Jupiter Olympien, ou l'art de la sculpture antique considéré sous un nouveau point de vue 1814

Henri Baron de Triqueti Cleopatra Dying 1859

Echoes of Slavery

The second room presented a number of works that have complex and challenging relationships with race and slavery. These were all statues or images representing black women, often either in chains, or markedly sexualised, or both. Several were produced, or reproduced, in bronze to give colour to the body. The exhibition also included two contemporary works by black artists Sanford Biggers and Maud Sulter. I particularly liked Biggers's statue Nile, which was caved in black marble and had a West African Dan mask on the body of a Neoclassical human form representing originally the River Seine.

Deathly Women

This was the final room and had some startling statues, almost all femmes fatales. These included the man-eating serpent woman Lamia, by Sir George Frampton who was quite astounding and looked basically like Tilda Swinton - well Tilda Swinton in some wild garb!

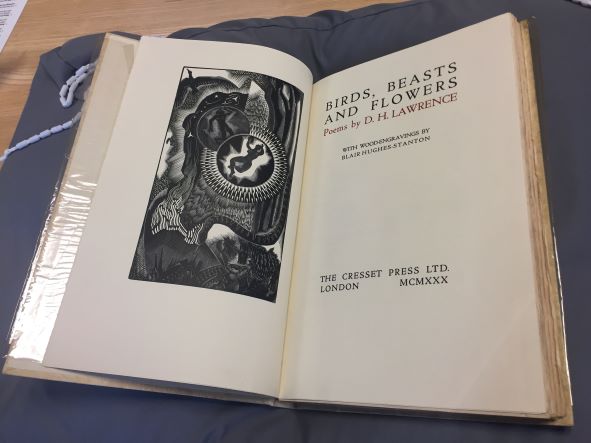

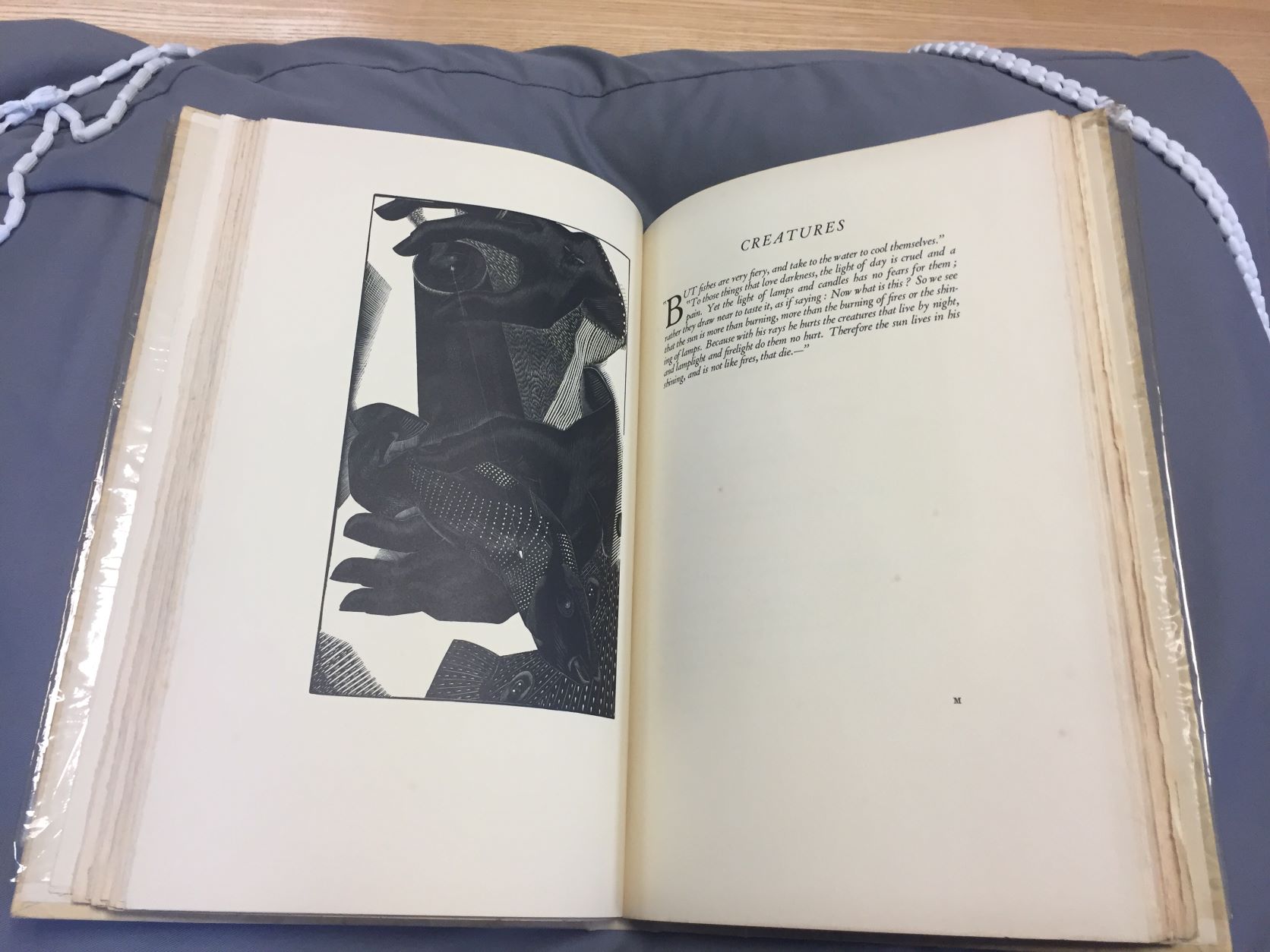

There was a Pandora by the Victorian sculptor Harry Bates, but the standout for me was another work by the same artist, Mors Janua Vitae 'Death, gateway of Life', illustrated below - made me think of some the imagery in the illustrations in Birds, Beasts and Flowers I think DH Lawrence might have approved!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A grand day out and I learned a lot from the exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute - just the right scale for an exhibit and a really excellent written guide and signage. Not really thought that much of the Victorian period in terms of arts (perhaps just the pre-Raphaelites) but I think this could be a really fascinating transitional period - so many social pressures and changes going on.

#

#