As a postgraduate on

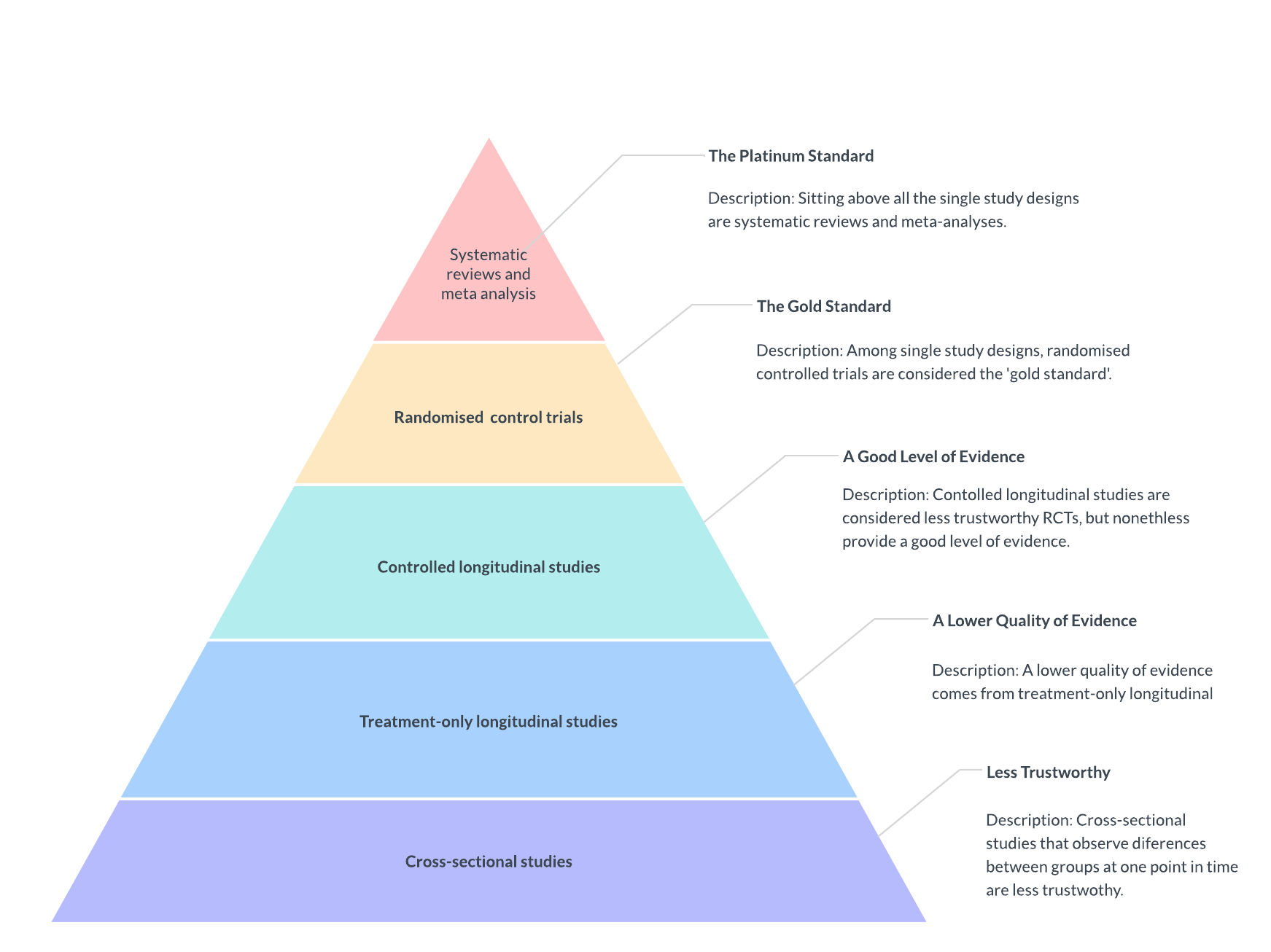

the MSc in HRM at the Open University Business School, in a 2-part blog

post, I took the liberty to summarise the basic premise of EBP with respect to Gifford’s

hierarchy and the four types of evidence (Open University 1a, 2023). In my

summary of Gifford’s hierarchy, I also critiqued the perspective of academic

and practitioner involvement in EBP citing the work of Dr. Carol Gill, an Associate

Professor of HRM at Melbourne Business School. In speaking with Dr. Gill, whose

work on evidence-based knowledge and management outlines various flaws in practitioner

involvement, I was interested to observe the pluralist[1] foundations in existence

with respect to HRM.

Because HR’s function is primarily non-client facing, in other words, because its role is fundamentally to operationalise other departments in a manner that optimises outlay and adds value, there are added pressures internally to continuously improve[2] its core offering as a budgeted expense. The setting for this pressure is increasingly a contested showdown between staunch advocates and unwary dissenters to the implementation of EBP. The pluralist debate concerning HR’s value in this respect is principled upon the idea that both quantitative and qualitative research practices can only denigrate HR’s value (Hughes and Hughes, et. al. 2021).

Now, the case for implementing EBP into people management is a relatively recent one, so much so that as recently as October this year an online article was published in People Management (Elder and Nikodem, 2023) which agrees with my blog post on Gill (1998) and her work concerning this thing called an awareness deficit. Elder and Nikodem (2023) state, “there is [perhaps] less awareness of academic evidence” that supports the argument in favour of implementation into HR, stating this lack exists with respect to employee empowerment programs and unconscious bias training initiatives. It should be noted that a perceived lack of awareness is one of the central arguments put forward by Gill (1998).

Discovering the CIPD Professional Map and the value of selective hiring

Vandenabeele and co-authors (2013) build on the work of Moore (1995) who writes on the topic of creating value in the public sector. Their paper states that the concept of strategy as it relates to HRM should be conceptualised more robustly than Moore’s case-study orientation. In the work of Moore, he essentially argues for something referred to as “public-sector production” (1995:53) which Moore explains is a type of public value that is not associated with a “physical good” or “consumed service” but rather created in the mind of the public executive to improve the lives of “particular clients and beneficiaries”. To implement this, Moore notes, in the case of strategic implementation[3] in diversified conglomerates, that because of a nuanced business context, key personnel could develop into, what he calls a “strategic asset” (1995:68).

How does this extract from Moore relate to evidence-based practice and recruitment? Well, firstly, Moore is resonated by Leisink and Steijn (2008) who regard “selective hiring” as part of a bundle of best HR practices (2008:118). Secondly, it supports the case for selective hiring, which is regarded by several labour economists as the artistic translation for Pissarides (2000) and his search and matching formulae (Merkl and van Rens, 2019). Vandenabeele et. al. (2013) point out in their paper what Moore fails to achieve; to define a structural framework that outlines the findings of his extensive study for application in the conglomerate context. Regarding the strategic advantage of key personnel in a conglomerate, the work of Vandenabeele and co-authors is resolved by the CIPD Profession Map (Elder and Nikodem, 2023). The Professional Map sets out what the CIPD call the “international benchmark”.

References

1. Elder, S.R. and Nikodem, M. (2023) “Considering the application and relevance of evidence-based HR”, People Management, Available at: https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1845833/considering-application-relevance-evidence-based-hr [Online] (Accessed on 30 November 2023)

2. Gill, C. (1998) “Don’t know, don’t care: An exploration of evidence-based knowledge and practice in human resource management”, Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), pp. 013-115

3. Hughes, J., Hughes, K., Sykes, G., Wright, K. (2021) “Moving from what data are to what researchers do with them: a response to Martyn Hammersley”, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(3), pp. 399-400

4. Learmonth, M. (2008) “Speaking Out: Evidence-Based Management: A Backlash Against Pluralism in Organisational Studies?”, Organization, 15(2), pp. 283-291

5. Leisink, P. and Steijn, B. (2008) “Recruitment, Attraction and Selection”, chapter in Perry, J. and Hondeghem, A. (eds) ‘Motivation in Public Management: Call of Public Service’, Norfolk: Oxford University Press

6. Malloch, H. (1997) Strategic and HRM Aspects of Kaizen: A Case Study. New Technology, Work, and Employment. [Online] 12 (2), pp. 108–122.

7. Merkl, C. and van Rens, T. (2019) “Selective Hiring and Welfare Analysis in Labour Market Models”, Labour Economics, 57(1), pp.117-130

8. Moore, M. H. (1995) ‘Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government’, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

9. Open University 1a (2023) “Gifford’s Hierarchy and Carol Gill on the “Knowing and Belief” Gap”, [Online] Available at https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=279019 (Accessed on 24 November 2023)

10. Pfeffer, J. and Sutton, R. I. (2006) ‘Hard Facts, Dangerous Half-Truths, and Total Nonsense: Profiting from Evidence-Based Management’, Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press

11. Pissarides, C. (2000) ‘Equilibrium Unemployment Theory’, Second Edition, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

12. Vandenabeele, W., Leisink, P. and Knies, E. (2013) ‘Public value cation and strategic human resource management: public service motivation as a linking mechanism’, chapter in Leisink, P., Boslie, P., van Bottenburg, M. and Marie Hosking, D. ‘Managing Social Issues: A Public Values Perspective’, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 37 – 54 [Online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781006962.00010 (Accessed on 30 November 2023)

[1] Here, practitioners should be weary of what some are calling “evidence-based misbehaviour” (Learmonth, 2008) that is, insubordination with good intentions (Pfeffer and Sutton, 2006).

[2] This has been studied extensively in the UK and can be attributed directly to the Japanese management concept known as Kaizen (Malloch, 1997) which has brought forth the modern principles of Lean and Six Sigma as applied to Human Resource Management. One of the most important of these principles is of course, ‘improvement’.

[3] There is also a compelling case for operative implementation.

This post was written by Alfred Anate Mayaki, a student on the MSc in HRM, and was inspired by a book by Mark H. Moore entitled "Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government"