Chapter 13 of A223 'The Reformation and local communities', or at least part of it, is literally on my doorstep. The 'Pilgrimage of Grace' of 1536 is mentioned in the materials as an example of resistance to the Reformation, and a few years ago a local history group in my nearby market town of Pocklington set up a walking trail to commemorate it.

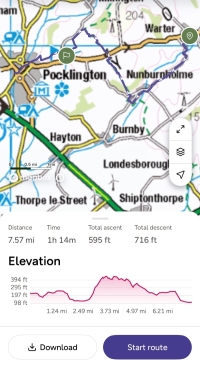

Like many trails, the actual route is determined by available access, and the connection with paths taken by anyone in 1536 are perhaps a little tenuous - but it was a lovely way to spend a Sunday morning.

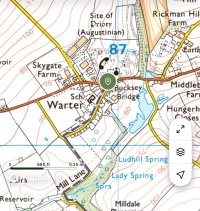

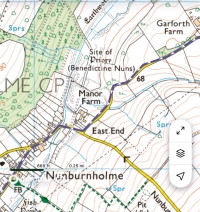

The logic of the trail is that it connects a couple of monastic sites with one of the locations that East Yorkshire rebels stopped at on their way towards York. The path runs from the village of Warter, which was the site of an Augustinian priory, through Nunburnholme, which had a small Benedictine nunnery, and ends in the town of Pocklington. Both the religious houses at Warter and Nunburnholme had been dissolved earlier in 1536 and the 'Pilgrims' reinstated them during the rebellion.

This is the church of St James in the village of Warter, it stands on the site of the former priory church. It was recorded that there were 12 canons resident at the time it was suppressed in August 1536; there are records of fine vestments, plate and jewelry and a holy relic, 'St James hand'. The sub-prior and the kitchener of the priory (their names aren't recorded) participated in either the 1536 'Pilgrimage' or the subsequent rebellions of early 1537 - they were executed in York in February of that year.

The walk takes you along quiet back roads to the village of Nunburnholme, the Benedictine priory there was one of the smallest and poorest religious houses in the county - six nuns had been living on the site at the time of dissolution (Warter priory had been valued at £140, Nunburnholme only managed £10 3s 3d).

There is nothing left to see of the nunnery, but it was located to the right of the beck as you look eastward up the valley.

Fortunately there's a very handy sign attached to the bus stop, which gives an idea of what the village might have looked like!

The path doesn't really need much signage, but if you look closely on the signpost you can possibly pick out the banner of the five wounds of Christ that was used by the rebels and is the logo for the trail.

(This is a really grim looking selfie - promise I was enjoying this a lot more than it looks 🤣)

The picture below is taken looking south-west from the edge of the Yorkshire Wolds, out over some of the area from which many commoners were drawn into the rebellion. There were a number of separate groups forming across East and North Yorkshire; the body of men that stopped at Pocklington were on there way to York under the leadership of the one-eyed lawyer Robert Aske, who would have a key role in drafting their oath as well as the '24 Articles' that we look at in the module materials.

The trail stops off at the Georgian mansion at Kilnwick Percy, shown below. There is a slight link with Henry VIII (if not the Pilgrimage of Grace) as it was built on the site of a tudor manor house owned in 1536 by Sir Thomas Heneage, who had just been appointed as the king's 'Groom of the Stool'!

As we probably all got to module A223 via module A111 (with its chapter on Buddhism and compassion) I couldn't resist highlighting that Kilnwick Percy is now in fact a Buddhist retreat - I had a hot chocolate at its 'World Peace Cafe' (to be honest with things as they are at the moment, every little helps!!)

Finally, after about eight miles, the walk ends up at All Saints church in Pocklington, which was looking very impressive in the sunlight today.

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a complex rebellion, with a mixture of aims and objectives, some about religion, some about political and economic tensions between 'North' and 'South' - but provides a fascinating 'what if...', it does feel that for a short period in 1536/7 the 'top-down' English Reformation was in very serious trouble.

Martin Huth (Deputy Head of Missions, German Embassy) - gave a potted history of museums and collection in Germany. From the Renaissance an increased interest in ancient art and the beginnings of art collections started with state rulers in the Holy Roman Empire. This became more widespread amongst German elites after 1848, collection became fashionable and was accompanied by a developing scientific interest in ethnology. Germany was a relative 'latecomer' to European colonialism, but as this developed it brought a boost to collection. He highlighted that in the mid 20th century Germany had both perpetrated and been the victim of cultural looting; plundering art works from Jewish people and conquered populations and then losing materials to Soviet Union and Western Allies. He brought up the term the 'nationalisation of art' to describe current desires to repatriate art that had been seen to have been stolen. Huth dated a change in culture to the late 1960's with student activism and subsequent discussions in the 1970's about it being untenable to retain artefacts like Benin Bronzes. He was keen to hear what Nigerian civic society wanted as the model for display of the art and asked whether a 'museum culture' was something that African society wanted to embrace, or was this an overly Eurocentric view?

Martin Huth (Deputy Head of Missions, German Embassy) - gave a potted history of museums and collection in Germany. From the Renaissance an increased interest in ancient art and the beginnings of art collections started with state rulers in the Holy Roman Empire. This became more widespread amongst German elites after 1848, collection became fashionable and was accompanied by a developing scientific interest in ethnology. Germany was a relative 'latecomer' to European colonialism, but as this developed it brought a boost to collection. He highlighted that in the mid 20th century Germany had both perpetrated and been the victim of cultural looting; plundering art works from Jewish people and conquered populations and then losing materials to Soviet Union and Western Allies. He brought up the term the 'nationalisation of art' to describe current desires to repatriate art that had been seen to have been stolen. Huth dated a change in culture to the late 1960's with student activism and subsequent discussions in the 1970's about it being untenable to retain artefacts like Benin Bronzes. He was keen to hear what Nigerian civic society wanted as the model for display of the art and asked whether a 'museum culture' was something that African society wanted to embrace, or was this an overly Eurocentric view? John Asien (Nigerian Copyright Commission) - was very measured about concerns over the recent Presidential decree - he stressed that the Oba still had to work with others to ensure safe storage and display of the artefacts. He made an interesting point about ownership, highlighting that African culture stressed three parties in ownership,: ancestors, current and future generations.

John Asien (Nigerian Copyright Commission) - was very measured about concerns over the recent Presidential decree - he stressed that the Oba still had to work with others to ensure safe storage and display of the artefacts. He made an interesting point about ownership, highlighting that African culture stressed three parties in ownership,: ancestors, current and future generations. Prof Ken Okoli (Academic, Art Historian) - made interesting points about the sacred nature of the objects (something stressed by a number of speakers) this was something that was largely passed over in the A111 module materials. He proposed at one point that to view the objects, once returned, people would need to perform various ritual ablutions - and that the objects would need to be purified on return given their 'desecration' in the West. Along with a number of people on the panel and the audience he gave a strong 'Bini' perspective and was clear he thought the objects should be returned to the Oba.

Prof Ken Okoli (Academic, Art Historian) - made interesting points about the sacred nature of the objects (something stressed by a number of speakers) this was something that was largely passed over in the A111 module materials. He proposed at one point that to view the objects, once returned, people would need to perform various ritual ablutions - and that the objects would need to be purified on return given their 'desecration' in the West. Along with a number of people on the panel and the audience he gave a strong 'Bini' perspective and was clear he thought the objects should be returned to the Oba. Prince Akeni Prosper (Heir-apparent to the Throne of Elluega I, the Ovie of Ozoro Kingdom) - gave an impressive account of his families' connection back to the 17th century civil wars in The Kingdom of Benin and the magical properties of the artefacts. Whilst the arguments around restitution were familiar, it was very interesting to hear them so eloquently put in terms of a 'traditional' community leader.

Prince Akeni Prosper (Heir-apparent to the Throne of Elluega I, the Ovie of Ozoro Kingdom) - gave an impressive account of his families' connection back to the 17th century civil wars in The Kingdom of Benin and the magical properties of the artefacts. Whilst the arguments around restitution were familiar, it was very interesting to hear them so eloquently put in terms of a 'traditional' community leader.