Suppose we choose 10 digits 0-9 at random, one after another. For example, we might get

3, 0, 5, 2, 1, 5, 3, 1, 9, 2

How many distinct digits appear? In the example there were 6 –

0, 1, 2, 3, 5,

– but the answer could be anything from 1 (all the digits are the same), up to 10 (they are different).

Can we work out the expected number of distinct digits that appear; how many different digits show up on average?

Consider the probability that 0 does not appear. The probability of the first digit not being 0 is , because 9 out of 10 digits aren't 0. The probability that the second digit is not 0 is the same, and so on, up to the tenth digit.

The probability the none of the digits is 0, i.e. 0 does not appear, is therefore .

What then is the probability that 0 does appear. Well, this is easy. It either appears or it doesn't, and the two probabilities must therefore add up to 1. Hence the probability of 0 being present in our sequence is

This is equivalent to saying that the expected number of times 0 will come up is 0.651. But there was nothing special about 0, the calculation would be the same for the other digits.

Now imagine we keep a score of what distinct digits appear, counting 1 if a digit appears and 0 if it doesn't. The probability that a digit appears is 0.651, in which case it will contribute 1 to the total. and 1 - 0.651 = 0.349 that it does not turn up and contributes 0. So it will make a net contribute of 0.651 x 1 + 0.349 x 0 = 0.651.

Now here is a piece of utter magic. There is a theorem, "Linearity of Expectation" which says that to get the overall score across all the digits all we need to do is add up the individual scores! This is actually quite surprising but it's true.

So we can just work out 10 x 0.651 = 6.51 and that is the average number of distinct digits we expect to see.

I always like to simulate these answers, in case I have something horribly wrong, so here is a short Python program

digits = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

count = 0

trials = 1000000

for i in range(trials):

count = count + len(set(random.choices(digits, k=10)))

print('mean number of different digits =', round(count/trials, 2))

And here is the output

mean number of different digits = 6.51

But there is more. I started thinking what if we did the same thing in base 16, with 16 digits 0 - 9, A, B, C, D, E, F? Or used the whole alphabet of 26 letters, or went beyond that? Suppose we used a n-character alphabet?

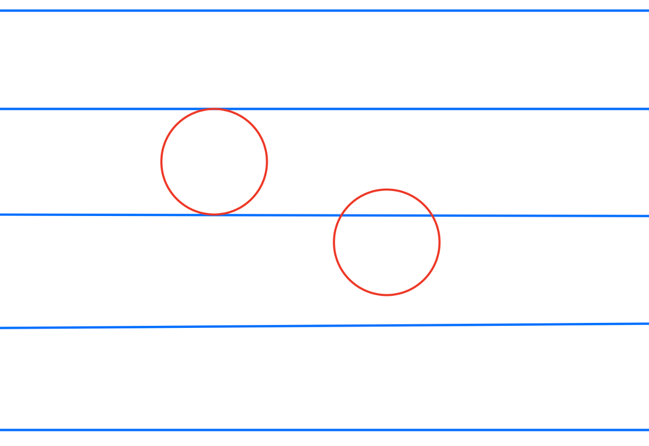

This smelt like a situation where Euler's famous number e ≈ 2.71828 might crop and when I investigated, there it was, right on cue. The beautiful result is that with an n-character alphabet, for large n the expected number of distinct characters in a run of n random choices approaches