After intensive strike action, Universities UK have now come forward with a proposal to staff in universities on the Universities Superannuation Scheme which the union has put to members to be voted on.

There has been intense argument on social media about which way to vote. It is clearly very important that all UCU members vote in order to come to a sound democratic decision on whether the offer about pensions is good enough, and we can suspend (not end) strike action and go back to teaching as normal, or should we reject the offer and continue to strike.

I have been on holiday and will have to come back onto email in order to vote. I have done my best to look at material about the offer while also taking time off with my young daughter. I am going to vote in favour of accepting the offer.

The offer is a substantial move from the employers' original position, which was that they would not negotiate - they have gone with the union to ACAS to do so, and that they were determined to move from a defined benefits scheme because of a massive deficit in the pension budget. They have now agreed to a joint board chosen equally by the employers and the union which will re-valuate the deficit, and they have recognised that the vast majority of those of us who have invested in the pension fund want a secure defined benefits scheme rather than what one speaker at a rally described as the 'chocolate teapot' of a pension which they tried to make us accept.

Why would we not accept this offer? So far as I can see, people against it have no trust in UUK and expect them to renege on their offer. There has been a lot of detailed unpicking of the wording of the offer, suggesting it is full of little loopholes.

I do not trust UUK either, but I trust the process. I trust that ACAS and the union, who have brought us this far, will watch over my interests. Sally Hunt raised her serious concerns about the pension proposals from very early on and the union worked extremely hard to get us to come out on strike at all. I believe they have a good understanding of what is going on.

People also complain that the proposal should not have been put to members, as it is merely a suggested process not a complete cave-in by the employers. I say: Let's be magnanimous. We, the employers and the British media (see articles not only in The Guardian and Times Higher Education Supplement, but even in the Financial Times) know that the employers were caught with their pants down. They were stupid to assume they could put such a poor valuation assessment of our pension fund in front of university staff, who include Emeritus Professors of Economics, Business Studies, Pension experts, Statisticians and many others who took their chocolate teapot apart in blogposts and explained exactly where the beans had come from. Let's allow them to pull their pants back up in private in the joint re-valuation committee.

We had to be allowed to vote on this proposal now, because if we left the vote any longer, we would not have time to vote before having to take strike action during assessment. We must have a democratic mandate if we are to do that.

Those who say Reject the offer, argue that we should not lose momentum. They believe the employers only want to get us through the crucial exam period and then will renege on their words.

I believe that the process will not allow them to do this, and that they are under scrutiny not just from our union and ACAS, also from interested media and therefore the public (including supportive students and their families). Exams are like spring. They come round every year (eventually). We are suspending our action, not ending it. If as the months go forward, UUK do renege on their recognition of the kind of pension we want to invest in, we will be able to strike during exam period next year.

We would be able to do that with continued popular support. I believe that if we drag the strike on this year in the face of an offer from the employers, we will lose the vital support we have had from students and their families, the media and many key politicians. (Perhaps that is what the employers hope will happen.)

But yes - we need to keep up pressure.

We need to do this by moving on from the battle over pensions. Perhaps it is not won yet. However, we need to leave picked personnel to take care of that for us (like union officers and our chosen members of the committee to re-consider the valuation of the pension fund, and lawyers who could oversee the process for us).

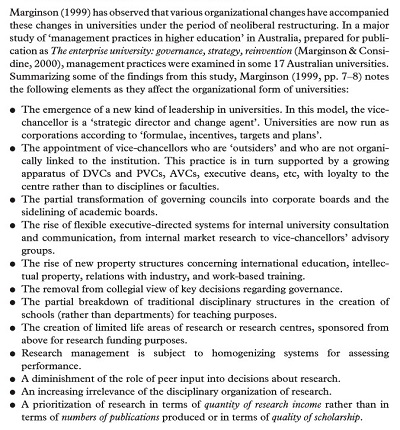

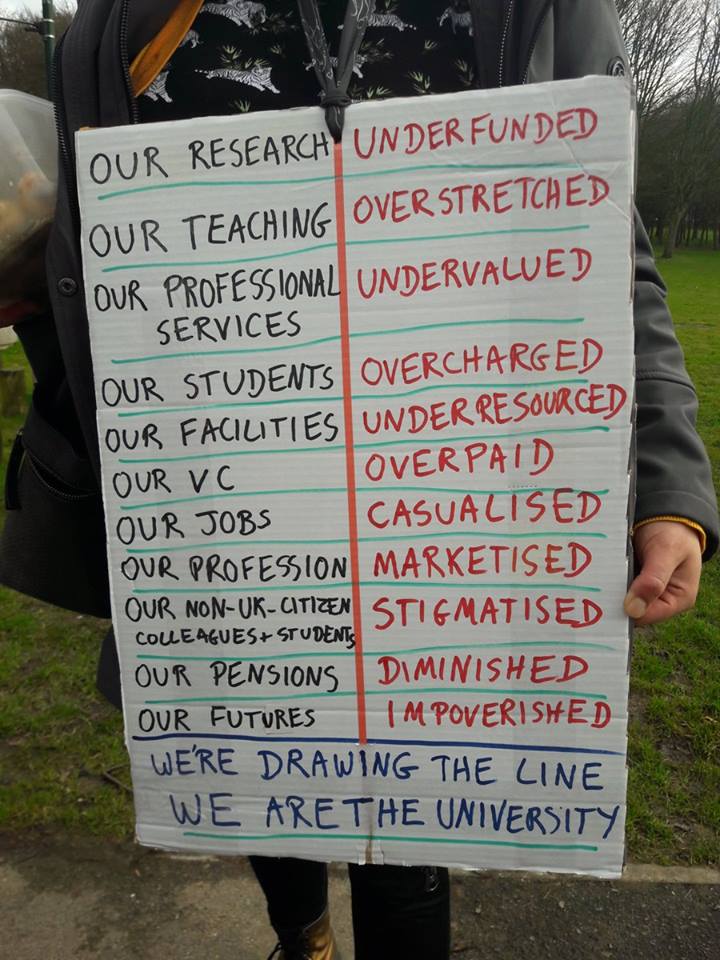

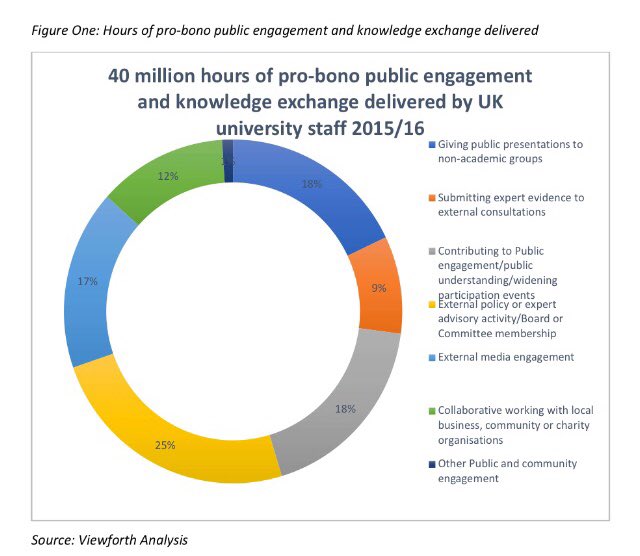

We should move on to other aspects of the neoliberalisation of universities. This is where the real deal is. Issues over our pensions arose because of the general trend of universities towards marketisation. There are several other fronts where we need to focus attention in order to win the war.

- We at the Open University are dealing with a vote of No Confidence, not just in our Vice Chancellor in person but in the whole Executive who have sought to introduce neoliberal principles to the detriment of our social justice mission. I regard this as a test case in education values: should education be market-driven, or driven by humanism.

- Coventry University have had an organisation imposed on them which means they can't stand collectively with the rest of us in the University and Colleges Union. We must defend our collective bargaining position.

- Casualisation blights our teaching and research provision.

- Our workloads have gone through the roof. Tiredness and stress are leading to health issues which affect most academics - while universities trumpet their support for student mental health initiatives.

I want to shift my efforts now to raising awareness of those problems, with my voice and my political will. (After I have had what's left of my holiday! So far I've only had to sort out one poor student in difficulties so it's been a good break

Oh, and I recruited another student for the Open University in Scotland who was unable to access traditional university and thrilled when she realised that she could study with us - for free, and without having to do a lot of GCSEs first. You owe me one @OUScotland.)

From a short walk in Roslin Glen.